Sunday 5 September 2021, Eskisehir, Turkey

One of the harsh realities of living in Asia is, contrary to popular belief, that to succeed, even superficially, a person is required to work extremely hard, which means for those with a job working long workdays, six days a week minimally.

I, as an ESL teacher, though my days tend to be 4 to 6 hours per workday, am required to work six days a week, from Sunday to Friday.

Today, for example, I had three Encounters (small classes where I elicit the English language from my students), two Social Clubs (where the students practice their English together on topics chosen for them – today was emotions and health) and a Complimentary Class (where the students practice their combined units learning of English in a less stresssful Encounter format).

As I reflect back on today’s workday – I keep a record of the teaching I do – I find myself feeling reflective about recent events.

Shabnam, the young Iranian who first recruited me into Wall Street English Eskisehir, had her farewell party on 21 August, the school recently celebrated the birthdays of three WSE staff (Romina, Nuri and Rasool), and next week Ece, one of WSE’s competent administrators, will marry her boyfriend this coming Saturday.

We are our own little society, our own little sub-culture, with all the tensions and joys of a dysfunctional family of strangers brought together at this junction of our lives.

I realize the more my life intertwines with theirs how deeply their lives matter to me.

I will not pretend that I understand half of our group in terms of the way they think and act.

Nor do I imagine that they comprehend me.

But they generate all manner of feelings from within me and are, for the most part, a positive boon for my mental health.

Soon Shabnam will leave us and Eskisehir and Turkey for a new life in Germany, and I can only imagine how she must be feeling.

And I find myself wondering if, God willing, I one day voluntarily leave WSE and Eskisehir and Turkey, what will I feel, how will my farewell be?

It is this theme of farewell that fills my thoughts as I reflect on the significance of the 54th day of the calendar – I am a wee bit slow admittedly with this accounting of the days, it now being the 248th day of the year – for six days from 23 February 2021 I would leave Switzerland for Turkey, Landschlacht for Eskisehir, with a farewell looming on the horizon, with great uncertainty as to what the future would hold.

Change is an immutable truism that cannot be halted.

It is how we deal with change that defines us.

Tuesday 23 February 2021, Landschlacht, Switzerland

I don’t remember much about the weather of the day or what I did on that day, save for writing and reading and preparing for my imminent departure.

The headlines were filled with the usual tales of armed conflicts and attacks, the noting that the last statue of Spanish dictator Francisco Franco was removed in Melilla, endless conversation about the corona virus and how the world is (mis)handling its treatment and reoccurrence, Iran’s petulance and intent of denying international inspections of its nuclear installations, the odd report of a man’s rampage of stabbing two police officers and attempting to stab two passers-by in Milan before he was shot dead by police, rioting and gang violence in three prisons in Ecuador, Malaysia’s disgraceful deportation of 1,086 Burmese civilians back to Myanmar, the dirty deals between Facebook and the Australian government allowing the social media forum to make agreements with Australian news media despite the laws of the land that make social media forum pay for using Australian news content, and American golfer Tiger Woods’ car accident.

All of these interesting to read.

None of these have little to do with my life in Landschlacht.

Somehow headline news and I have successfully avoided one another for most of my life.

It is in the reading of history that I am emotionally involved, intellectually compromised.

/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/prisa/FJQSK272EVFR7L4IONCBYTJYXI.jpeg)

Saturday 23 February 632 (10 AH), Mecca, Saudi Arabia

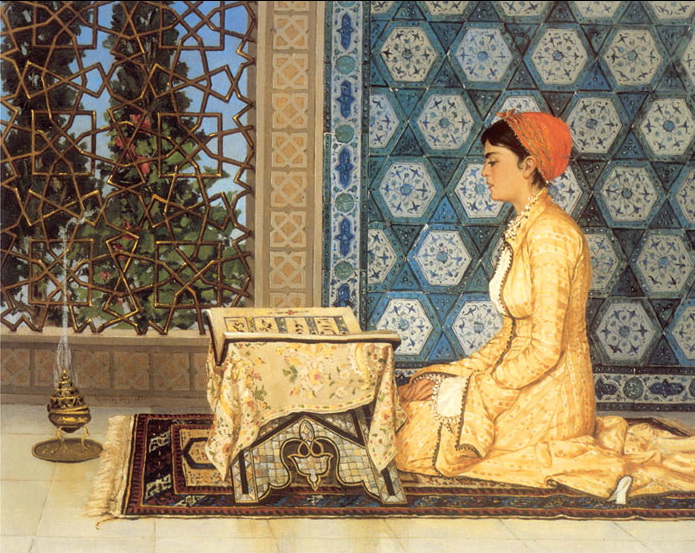

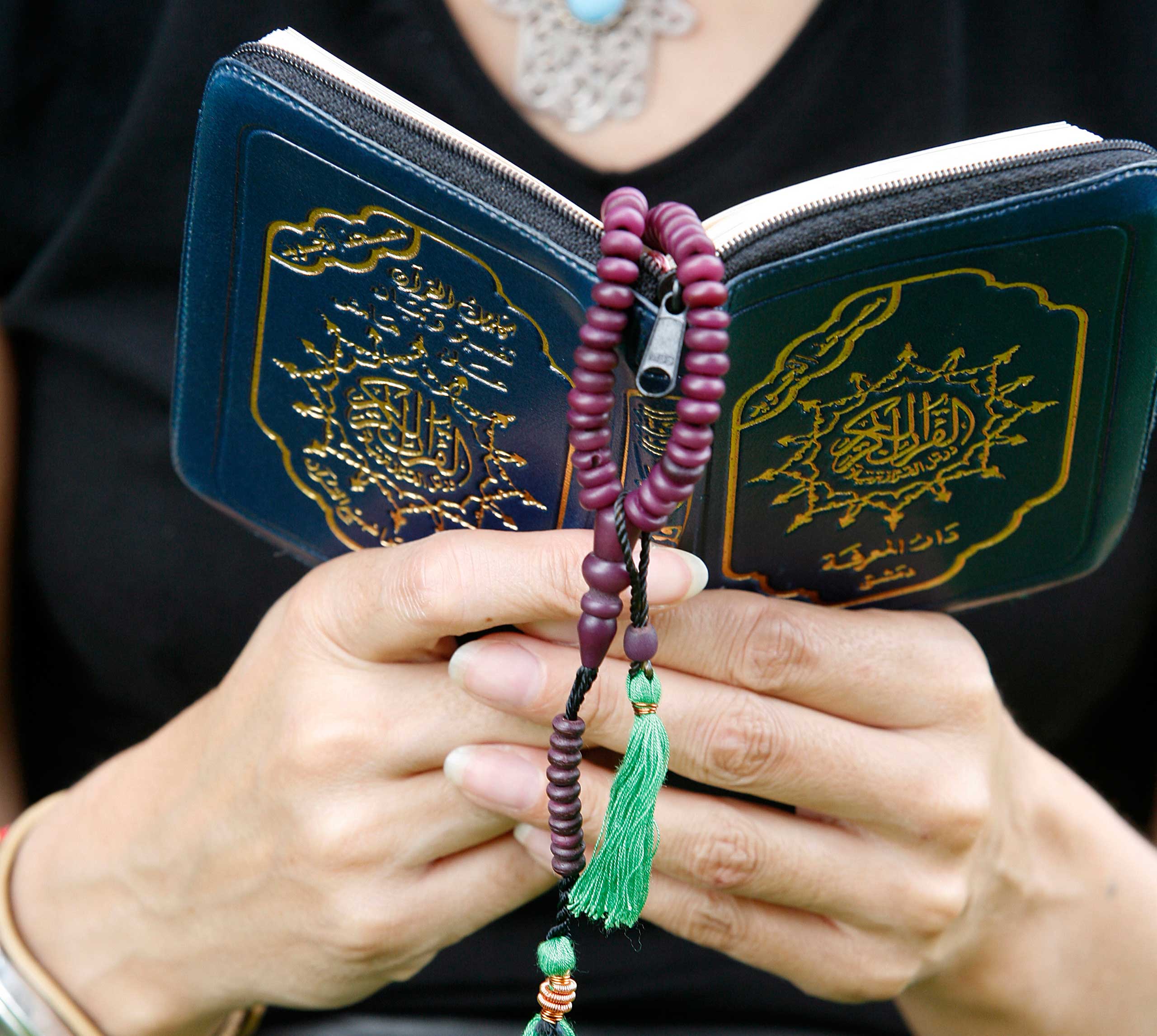

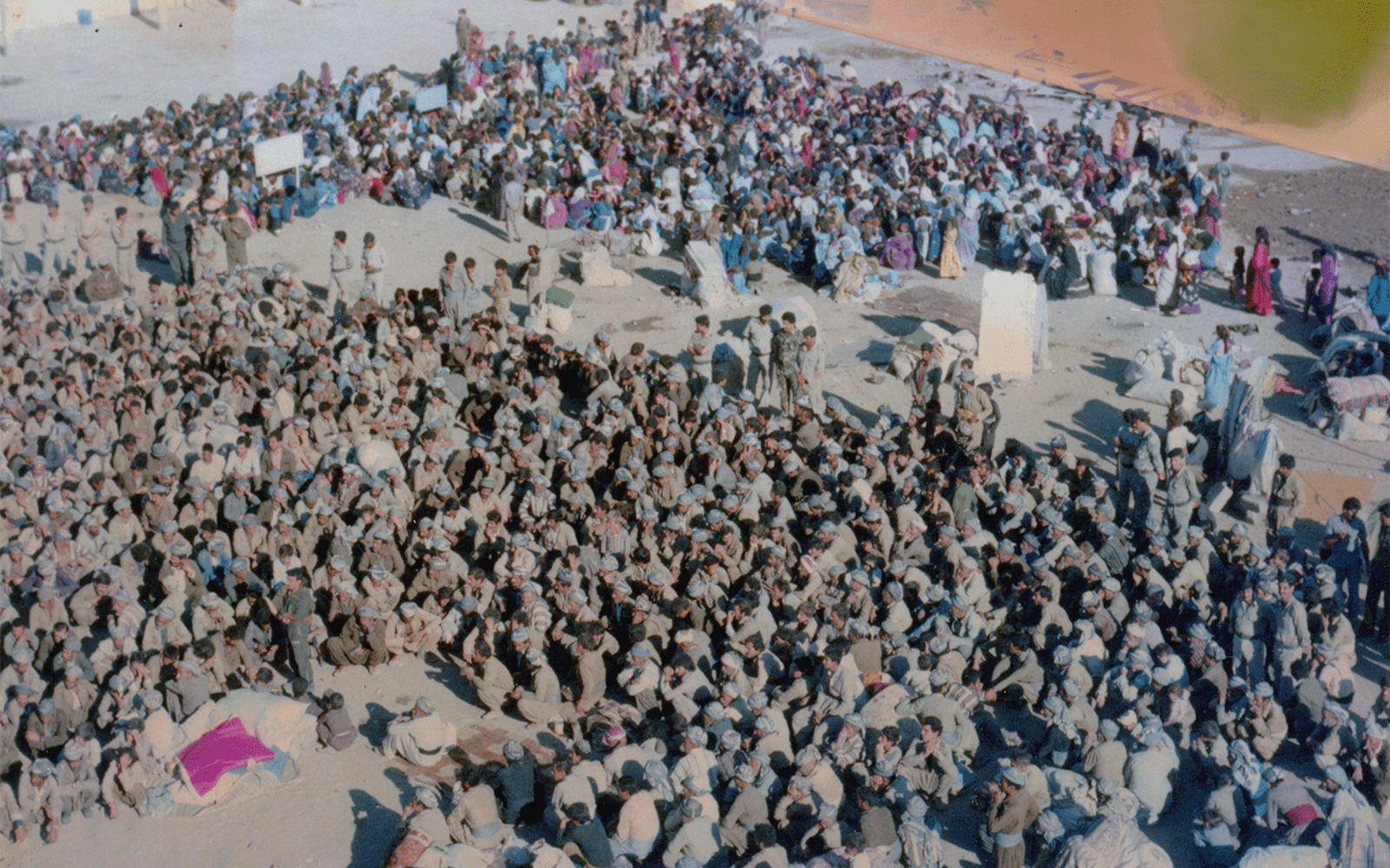

The Prophet Muhammad completed his life with a pilgrimage to Mecca, which was the 10th year after his migration to Medina (the event known as the Hijira) and hence dated 10 AH in the Islamic calendar.

He thus initiated the practice of pilgrimage (hajj) to Mecca that Muslims, wherever they reside, are supposed to attempt at least once in their lifetimes.

During the pilgrimage, on which he was accompanied by tens of thousands of supporters, he gave his final sermon on 23 February and completed the Islamic holy book of revelations, the Qu’ran (Koran).

In the account of Shia Islam, Muhammad was also said to have chosen his cousin and son-in-law Ali as his successor – a claim that has divided Shi’ite and Sunni Muslims ever since, with the later group instead following a line of leadership stretching back to Muhammad’s close associate and the first Caliph, Abu Bakr.

The text of the sermon itself is disputed and several versions exist.

Muhammad died on 8 June 632, in his wife’s house in Medina, aged 63.

“O people, lend me an attentive ear, for I know not whether after this year, I shall ever be amongst you again.

Therefore listen to what I am saying to you very carefully and take these words to those who could not be present here today.

O people, just as you regard this month, this day, this city of Mecca as sacred, so regard the life and property of every Muslim as a sacred trust.

Return the goods entrusted to you to their rightful owners.

Hurt no one so that no one may hurt you.

Remember that you will indeed meet your Lord and that He will indeed reckon your deeds.

God has forbidden you to take usury (lending of money with interest), all interest obligation shall henceforth be waived.

Your capital, however, is yours to keep.

You will neither inflict nor suffer any inequity.

God has judged that there shall be no interest and that all the interest due to Abbas ibn Abd’al Muttalib (Muhammad’s uncle) shall henceforth be waived.

Beware of Satan, for the safety of your religion.

He has lost all hope that he will ever be able to lead you astray in big things, so beware of following him in small things.

O people, it is true that you have certain rights with regard to your women, but they also have rights over you.

Remember that you have taken them as your wives only under God’s trust and with His permission.

If they abide by your right then to them belongs the right to be fed and to be clothed in kindness.

Do treat your women well and be kind to them for they are your partners and committed helpers.

And it is your right that they do not make friends with anyone of whom you do not approve, as well as never to be unchaste.

O people, listen to me in earnest, worship God, say your five daily prayers (Salah), fast during the month of Ramadan, and give your wealth in Zakat (alms to the poor).

Perform Hajj (pilgrimage to Mecca) if you can afford to.

All mankind is from Adam and Eve.

An Arab has no superiority over a non-Arab nor a non-Arab has any superiority over an Arab.

Also a white has no superiority over black nor a black over white, except by piety and good action.

Learn that every Muslim is a brother to every Muslim and that Muslims constitute one brotherhood.

Nothing shall be legitimate to a Muslim which belongs to a fellow Muslim unless it was given freely and willingly.

Do not, therefore, do injustice to yourselves.

Remember, one day you will appear before God and answer your deeds.

So beware, do not stray from the path of righteousness after I am gone.

O people, no prophet or apostle will come after me and no new faith will be born.

Reason well, therefore, o people, and understand words which I convey to you.

I leave behind me two things, the Qu’ran and my example, the Sunnah.

If you follow these you will never go astray.

All those who listen to me shall pass on my words to others and those to others again.

May the last ones understand my words better than those who listen to me directly.

Be my witness, o God, that I have conveyed Your message to Your people.”

(The Prophet Muhammad, Farewell Sermon, 23 February 632 CE / 10 AH)

Muhammad said it very succinctly:

“O people, lend me an attentive ear, for I know not whether after this year, I shall ever be amongst you again.“

We all foolishly believe we have more time, but in truth we know not.

“O people, just as you regard this month, this day, this city of Mecca as sacred, so regard the life and property of every Muslim as a sacred trust.

Return the goods entrusted to you to their rightful owners.

Hurt no one so that no one may hurt you.“

Oh, if only all Muslims practiced Islam and all Christians practiced Christianity and all Buddhists practiced Buddhism in the ways the founders of these faiths intended….

“O people, it is true that you have certain rights with regard to your women, but they also have rights over you.

Remember that you have taken them as your wives only under God’s trust and with His permission.

If they abide by your right then to them belongs the right to be fed and to be clothed in kindness.

Do treat your women well and be kind to them for they are your partners and committed helpers.

And it is your right that they do not make friends with anyone of whom you do not approve, as well as never to be unchaste.“

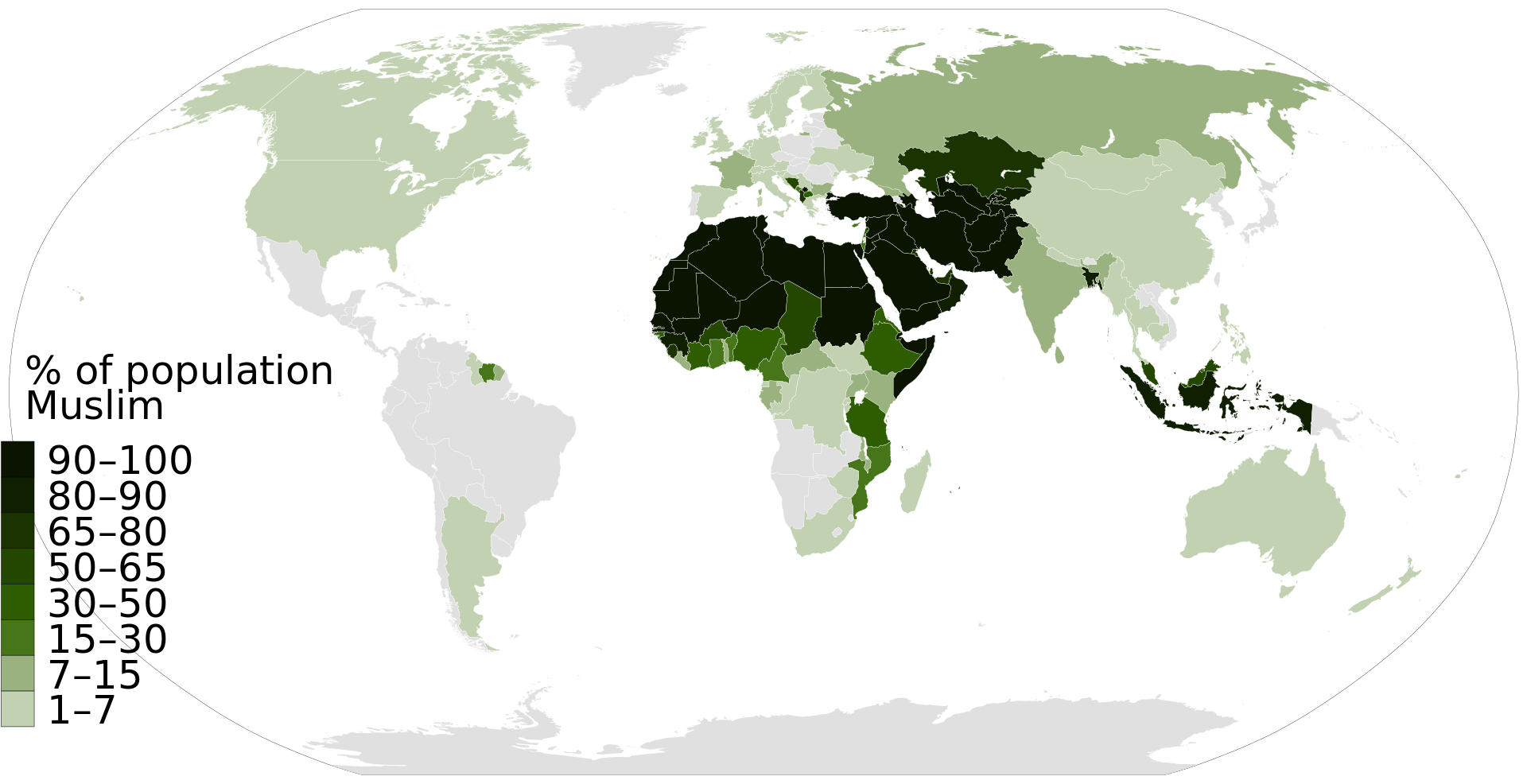

Women undoubtedly have an important role to play within the family unit under Islam, but one of the most controversial issues preventing lasting harmony, if not integration, between Muslim and non-Muslim is the status of women within society.

In some Islamic countries, women are not allowed to travel far afield, meet a man, or take part in various activities, without the permission of the male head of the house, whether father, husband or brother.

This may seem strange to non-Muslims, but their parents’ generation will doubtless remember how, in childhood, they were expected to seek their fathers’ approval before they did anything of import.

Even now, we could hardly say that the mantra “Ask your father.” has completely disappeared.

Perhaps before non-Muslims attack Islam for being patriarchal, sexist and cruel, they should consider that the secular West has only really moved on in the past 75 years.

Even after the Second World War, which was a catalyst to the Sexual Revolution, it was still common for politicians when canvassing to ask women how their husbands would be expecting them to vote.

It was generally felt that men were more competent to make major decisions than women, although the women’s interests and opinions would have been considered.

Is religion to blame for what many see as the unfair treatment and low social status of Muslim women in our modern age?

Or are cultural practices that have predominated for centuries to blame?

In order to unravel the question, Muslim scholars refer us initially to the context of society during Muhammad’s lifetime, when the social status of women in Arab society – as in the West – was exceedingly low.

Despite the elaborate rhapsodies to women in the songs and music of the Arabian lands at this time, the adoration of women was more inspired by carnal lust and feelings of ownership than by a true understanding of their potential, their dignity or their humanity.

Women at that time were often accorded treatment little better than that lavished upon a favourite horse.

Prostitution was a recognized profession.

Captive women, kept as handmaids, were forced to make money for their masters, who were also their pimps.

Husbands were more interested in the continuation of the family than having the exclusive sexual rights to their wives.

Married women who had not conceived were allowed by their husbands to have sex with others so as to improve their chances of becoming pregnant, a practice known in the Islamic world as istibdza, which was also known to operate at one time or another in many other societies.

Women in the days before the Prophet Muhammad were treated as chattels.

A woman was not entitled to inherit any share of the estate of her deceased husband, father or other relation.

On the contrary, she herself was inherited as part of the property.

The man who inherited her could, if he wished, marry her, but he might instead choose to lend or give her to someone else.

On the death of his father, a son could even marry his stepmother.

Like sheep, camels and carpets, she was part of his inheritance.

A man could repeatedly divorce his wife, then take her back again, provided it was within a prescribed period known as ‘iddah.

He could swear never to have sexual relations with the spurned woman again, but resume relations if the mood took him.

He could declare that henceforth he would look upon her “as his mother“, so that for an unspecified time she had little idea of her future role.

A woman’s life was devoid of security.

The revolution of Arab society heralded by the advent of Islam and the teachings of the Prophet brought about a change in the status of women.

Qu’ranic injunctions against the abuse of women and the provisions made in Islam for their protection did for women what the Magna Carta in England did for government.

The Qu’ran gave women rights of inheritance and divorce, centuries before Western women were accorded similar benefits.

It did not, however, effect immediate or revolutionary change nor has it ever created equity in women’s rights.

Even now, women suffer restrictions in some Islamic countries that would never be tolerated in the West.

Muhammad taught men that the best among them was he who treated his woman best.

To plant respect and regard for women in a soil where infants of that sex were frequently buried alive was no easy task.

The birth of a daughter was no occasion for celebration in pre-Islamic Arabia.

(Nor, some women would argue, even now.)

Before Islam, the daughter would often have been disposed of to save her father’s face.

It was a mark of virility and power to father sons.

Women generally had little say in the fate of their daughters – it was their failure, too – and sometimes explicit agreement was given at the nuptial ceremony to the slaughter of female children.

There were cases in which the agreement went beyond this and decreed it would be the duty of the mother herself to perform the infanticide.

Such brutal practices came to an end at a single stroke, with the Qu’ranic words:

“And when the one buried alive is asked for what sin she was killed.”

If Muslims’ interpretation of and obedience of the Qu’ran has so far failed to accord the women even the status accorded to them by the Prophet, it has at least succeeded in outlawing the live burial of female children.

Once Islam became firmly established, there were no further recorded instances of this cruelty.

If the good that Muhammad achieved for women is weighed against the failure of Islam to achieve equality for them 1,400 years later, there can be little doubt that his influence was regarded as wholly positive.

The number of wives Muhammad had has been held against him by non-Muslims, but this reflected the customs of his own land in the times he which he lived.

There is much evidence that Muhammad was a loyal and devoted family man.

For many years, he remained monogamous, which was unusual in an Arabian country.

Khadija bore him four daughters, all of whom he treated with kindness and humanity.

Muslims maintain that Muhammad was a man who truly enjoyed the company of women.

Tradition holds that some of his male companions were astonished by his leniency towards his wives.

They were amazed at the way in which he allowed them to stand up to him.

He was scrupulous about helping with the chores and even mended his own clothes.

Whenever he had the opportunity, he sought out the companionship and counsel of his wives.

Not only would he take them on expeditions, but he would take their advice seriously.

Where their education was concerned, tradition holds that all the women in Medina were taught by Muhammad.

During his lifetime men were also being taught by knowledgeable and respected women.

Critics of Islam argue that the Qu’ran does appear to suggest the primacy of man over woman.

Woman proceeds from man.

She is chronologically secondary.

She finds her fulfillment through man.

She is made for his pleasure, his repose and his completion.

The primacy of the male seems to be exemplified by a much debated and misinterpreted verse, Surah 2:28, which if often translated as “Husbands have a degree of right over their wives.”

Muslim scholars of the 19th and 20th centuries have similarly used hadiths from the collections of Bukhari and Abu Muslim to support the argument that women are intrinsically inferior to men.

One scholar, Riffat Hassan, has examined these claims in detail and maintains all these hadiths can be traced to a contemporary of Muhammad called Abu Hurairah.

Such hadiths are most commonly dismissed as unreliable and do not reflect the sayings or beliefs of the Prophet.

They simply reflect prejudices that existed in early Islamic culture.

To what extent Islam is responsible is arguable.

The Qu’ran is all important to Muslims and is at the heart of all decisions taken, but the way in which its verses are interpreted varies.

The treatment of women has more to do with cultural practices and attitudes.

Muslims stress that, in fact, the Qu’ran makes women and men equal partners before God.

Women are not inferior, but created from the same soul.

However, each of the sexes has differing duties and responsibilities.

Every instruction given to Muslims in the Qu’ran refers to male and female believers alike.

Both sexes are judged by the same standards.

Both have the same religious obligations.

One hadith tells how the Prophet’s wife Salamah asked God one day why the Qu’ran‘s revelations never specifically mentioned women.

He replied by stressing the equality of both.

In Arabic, the word insan refers not just to men, but to both sexes.

“For men and women who are patient and constant, who humble themselves, who give in charity, who fast, who guard their chastity, and who engage in the praise of Allah.

Allah has prepared forgiveness and a great reward.“

That men and women have different roles according to Islam is exemplified by the Islamic view of a married couple, a view based on complementary harmony of the sexes, and where the dichotomy of the sexes is carefully marked out before God.

Man and woman are different.

The ideal state is a union of the two.

A harmonious union can only be achieved if the qualities both bring to the marriage are complimentary to one another.

In Islam, this principle, established first in a household, applies equally outside it.

Unity and harmony in the world can only be achieved if there is harmony between the sexes.

The best way of realizing that harmony is for a man to be masculine and for a woman to be feminine.

There should be no guilt or denial about the differences between the sexes.

These are, in fact, the very things that make them available and desirable to one another.

Such a dialogue between the sexes should be carried out in an atmosphere of mutual respect.

“All mankind is from Adam and Eve.

An Arab has no superiority over a non-Arab nor a non-Arab has any superiority over an Arab.

Also a white has no superiority over black nor a black over white, except by piety and good action.

Learn that every Muslim is a brother to every Muslim and that Muslims constitute one brotherhood.

Nothing shall be legitimate to a Muslim which belongs to a fellow Muslim unless it was given freely and willingly.

Do not, therefore, do injustice to yourselves.“

Muhammad was not only a religious leader but a political one.

He decided that an agreement was needed with all the tribes of the town to formalize his role.

Such an agreement between Muslims, Jews, Christians and pagans would be based on respect and mutual responsibility.

It would establish the rules of law and of being a citizen.

The Magna Carta of Muslims was to become known as the Constitution of Medina.

It is the earliest known model of government in Islam and was seminal in its recognizing of different faiths coming together to form the same ummah (brotherhood).

Sadly, no complete copies of the original agreement survive.

Yet the spirit of it was clear.

It was a message of plurality, of mutual, peaceful co-existence between different traditions and faiths, in one single community.

This important treaty contradicts the ambitions of any radical Muslims who might be seeking to develop one single, global caliphate of Islam.

It is all too often ignored and many non-Muslims are not aware of it.

Although Muhammad was recognized in Medina as a man of peace and reconciliation, his enemies in Mecca continued to plot against him.

He received a series of highly controversial revelations urging him to fight back.

It is these verses from the Qu’ran have given some modern groups carte blanche to wage war against their enemies, in their own eyes granting permission to carry out violence.

Moderate Muslims, however, refer back to the life of the Prophet himself, arguing that jihad is not about nationalism, tyranny or aggrandisement, but that war is acceptable only as a defence in the face of oppression.

Terrorist groups of today claim Muhammad as their inspiration, referring constantly to him to justify their actions and citing a revolution known today in the Qu’ran as the Sword Verse.

Scholar Abdullah Yusuf Ali translates it as:

“But when the forbidden months are past, then fight and slay the pagans wherever ye find them and seize them, beleaguer them and lie in wait for them in every stratagem of war.

But if they repeat and establish regular prayers and practice regular charity, then open the way for them.

For Allah is oft-forgiving, most merciful.“

Moderate Muslims stress that there were no recorded instances of deliberate attacks by Muslims in Muhammad’s lifetime.

All the rules of engagement are spelt out in great detail, ensuring that all the rules of engagement are spelt out in great detail, ensuring that women, children, the elderly and holy leaders are exempt from any violence.

In light of all this, Muhammad’s life and his Farewell Sermon, it is hard to believe Muhammad would have condoned the acts of violence committed today in the name of his religion.

From what is known, the Prophet during his lifetime created a united and coherent society with human values.

Above all, he preached tolerance and understanding, teaching that all of us are equal before God.

I am not suggesting that non-Muslims should suddenly embrace Islam.

What I am saying that what Islam is criticized for may be far from what Islam was intended to be.

Friday 23 February 1455, Mainz, Germany

The Gutenberg Bible (also known as the 42-line Bible, the Mazarin Bible or the B42) was the earliest major book printed using mass-produced movable metal type in Europe.

It marked the start of the “Gutenberg Revolution” and the age of printed books in the West.

The book is valued and revered for its high aesthetic and artistic qualities as well as its historic significance.

It is an edition of the Latin Vulgate printed in the 1450s by Johannes Gutenberg in Mainz, Germany.

Forty-nine copies have survived.

They are thought to be among the world’s most valuable books, although no complete copy has been sold since 1978.

It is estimated that following the innovation of Gutenberg’s printing press, the European book output rose from a few million to around one billion copies within a span of less than four centuries.

Samuel Hartlib, who was exiled in Britain and enthusiastic about social and cultural reforms, wrote in 1641 that “the art of printing will so spread knowledge that the common people, knowing their own rights and liberties, will not be governed by way of oppression”.

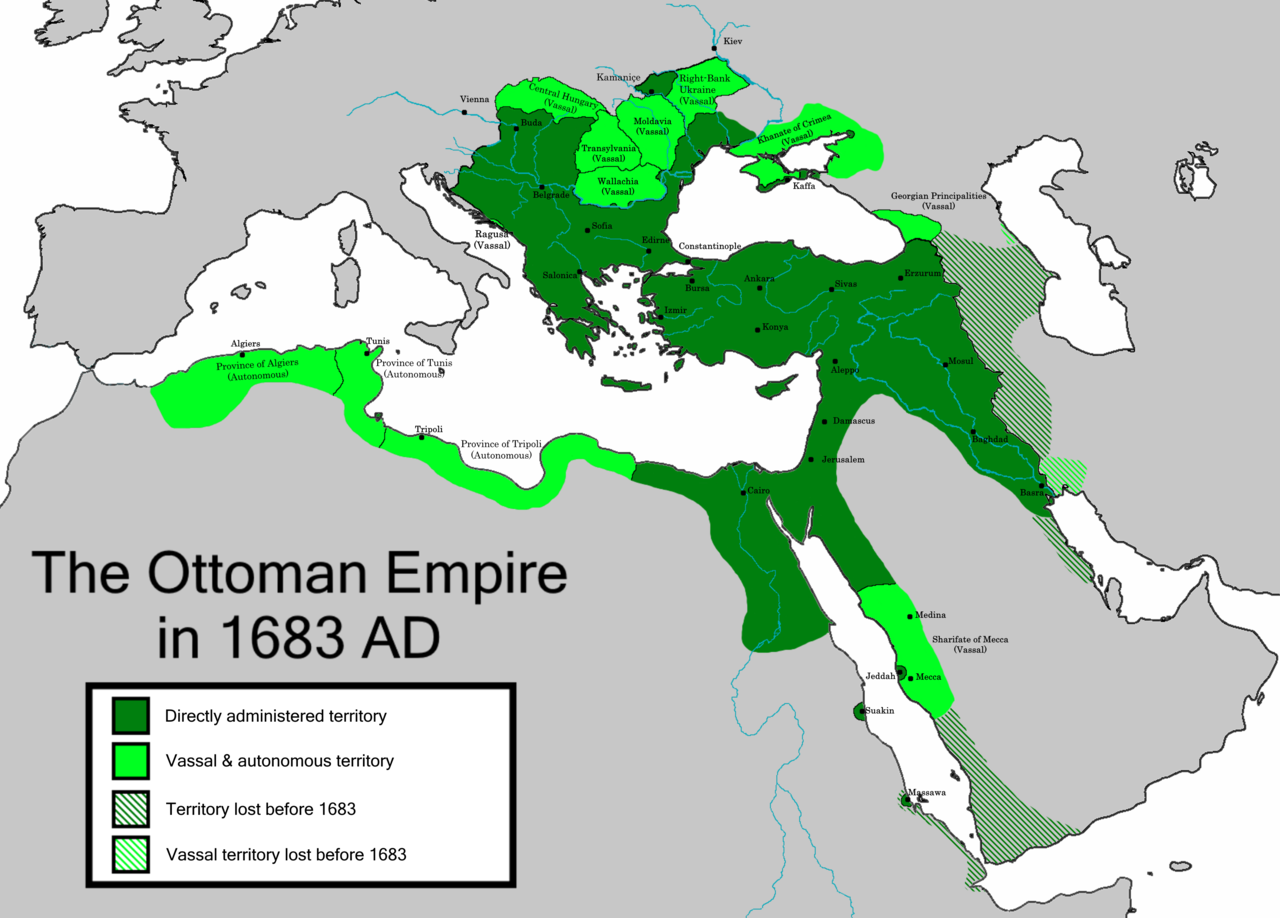

In the Muslim world, printing, especially in Arabic scripts, was strongly opposed throughout the early modern period, partially due to the high artistic renown of the art of traditional calligraphy.

However, printing in Hebrew or Armenian script was often permitted.

Thus, the first movable type printing in the Ottoman Empire was in Hebrew in 1493, after which both religious and non-religious texts were able to be printed in Hebrew.

According to an imperial ambassador to Istanbul in the middle of the 16th century, it was a sin for the Turks, particularly Turkish Muslims, to print religious books.

In 1515, Sultan Selim I issued a decree under which the practice of printing would be punishable by death.

At the end of the 16th century, Sultan Murad III permitted the sale of non-religious printed books in Arabic characters, yet the majority were imported from Italy.

Ibrahim Muteferrika established the first press for printing in Arabic in the Ottoman Empire, against opposition from the calligraphers and parts of the Ulama.

It operated until 1742, producing altogether seventeen works, all of which were concerned with non-religious, utilitarian matters.

Printing did not become common in the Islamic world until the 19th century.

Hebrew language printers were banned from printing guilds in some Germanic states.

As a result, Hebrew printing flourished in Italy, beginning in 1470 in Rome, then spreading to other cities including Bari, Pisa, Livorno, and Mantua.

Local rulers had the authority to grant or revoke licenses to publish Hebrew books, and many of those printed during this period carry the words ‘con licenza de superiori‘ (indicating their printing having been officially licensed) on their title pages.

It was thought that the introduction of printing ‘would strengthen religion and enhance the power of monarchs.‘

The majority of books were of a religious nature, with the church and crown regulating the content.

The consequences of printing ‘wrong‘ material were extreme.

Meyrowitz used the example of William Carter who in 1584 printed a pro-Catholic pamphlet in Protestant-dominated England.

The consequence of his action was hanging.

Print gave a broader range of readers access to knowledge and enabled later generations to build directly on the intellectual achievements of earlier ones without the changes arising within verbal traditions.

Print, according to Acton in his 1895 lecture On the Study of History, gave “assurance that the work of the Renaissance would last, that what was written would be accessible to all, that such an occultation of knowledge and ideas as had depressed the Middle Ages would never recur, that not an idea would be lost“.

Print was instrumental in changing the social nature of reading.

Elizabeth Eisenstein identifies two long-term effects of the invention of printing.

She claims that print created a sustained and uniform reference for knowledge and allowed comparisons of incompatible views.

Asa Briggs and Peter Burke identify five kinds of reading that developed in relation to the introduction of print:

- Critical reading: Because texts finally became accessible to the general population, critical reading emerged as people were able to form their own opinions on texts.

- Dangerous reading: Reading was seen as a dangerous pursuit because it was considered rebellious and unsociable, especially in the case of women, because reading could stir up dangerous emotions such as love, and if women could read, they could read love notes.

- Creative reading: Printing allowed people to read texts and interpret them creatively, often in very different ways than the author intended.

- Extensive reading: Once print made a wide range of texts available, earlier habits of intensive reading of texts from start to finish began to change, and people began reading selected excerpts, allowing much more extensive reading on a wider range of topics.

- Private reading: Reading was linked to the rise of individualism because, before print, reading was often a group event in which one person would read to a group. With print, both literacy and the availability of texts increased, and solitary reading became the norm.

The invention of printing also changed the occupational structure of European cities.

Printers emerged as a new group of artisans for whom literacy was essential, while the much more labour-intensive occupation of the scribe naturally declined.

Proof-correcting arose as a new occupation, while a rise in the numbers of booksellers and librarians naturally followed the explosion in the numbers of books.

Gutenberg’s printing press had profound impacts on universities as well.

Universities were influenced in their “language of scholarship, libraries, curriculum and pedagogy“.

Before the invention of the printing press, most written material was in Latin.

However, after the invention of printing the number of books printed expanded as well as the vernacular.

Latin was not replaced completely, but remained an international language until the 18th century.

At this time, universities began establishing accompanying libraries.

Cambridge made the chaplain responsible for the library in the 15th century but this position was abolished in 1570 and in 1577 Cambridge established the new office of university librarian.

Although, the University of Leuven did not see a need for a university library based on the idea that professors were the library.

Libraries also began receiving so many books from gifts and purchases that they began to run out of room.

However, the issue was solved in 1589 by a man named Merton who decided books should be stored on horizontal shelves rather than lecterns.

The printed press changed university libraries in many ways.

Professors were finally able to compare the opinions of different authors rather than being forced to look at only one or two specific authors.

Textbooks themselves were also being printed in different levels of difficulty, rather than just one introductory text being made available.

Thanks to the Gutenberg Revolution, today’s independent scholars can enter new fields of knowledge in ways that were never possible before.

How can you begin exploring new realms of learning?

The obvious first step would be to pull together the books in your local public library on the subject and thereby get an overview of the scope of the subject.

Select the most authoritative and recent comprehensive book to get a taste of the various areas within a field.

At the same time, dip into magazines, both at the library and at a local magazine store, for a stimulating glimpse of what is current and exciting in the field.

Such magazines, with their advertisements for the latest books, will also bring your awareness of the literature up-to-date.

A visit to a local centre of activity in the field will put you in touch with local practitioners and enthusiasts.

Usually, such places will have a bulletin board with notices about upcoming events in the field.

One or two of those meetings would give up the flavour of activity in the field in your area.

Thus, with a minimum of time you can dip into a field, get a sense of its scope and current thrust, meet some of the lively local experts, and participate in some interesting activities.

By this time, you would likely have come to some conclusion about your commitment to the field.

You might have identified an area you would like to investigate.

You will have learned how extensive networks of amateurs participate in the acquisition of knowledge.

Through these networks you can learn how to conduct scientifically significant observations and how to accumulate them in a useful way.

The means of finding out about a field are many, depending on your own style of learning.

Do you like nothing better than to settle down with five or six books on a given subject?

Or would you much prefer to listen to experts discussing the subject?

Would you like to meet someone who is knowledgeable in the field and learn more about it face-to-face?

Or would you like just to wander around a conference on the subject?

Every one of these options is available in virtually any field you choose, so the choice can hinge on your personal preference.

Ronald Gross calls the full range of these options:

The Invisible University.

This is what universities were before the ivy had centuries to grow:

People learning together.

There is no central quad, since the approach is to learn everywhere, from the infinite variety of databases, information sources and materials that exist.

There is an unlimited number of ways to learn: apprenticeship, tutorials, mentoring, work-study, correspondence, travel, reading, etc.

Wednesday 23 February 1820, London, England

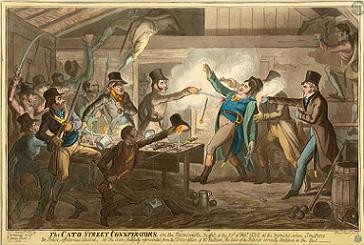

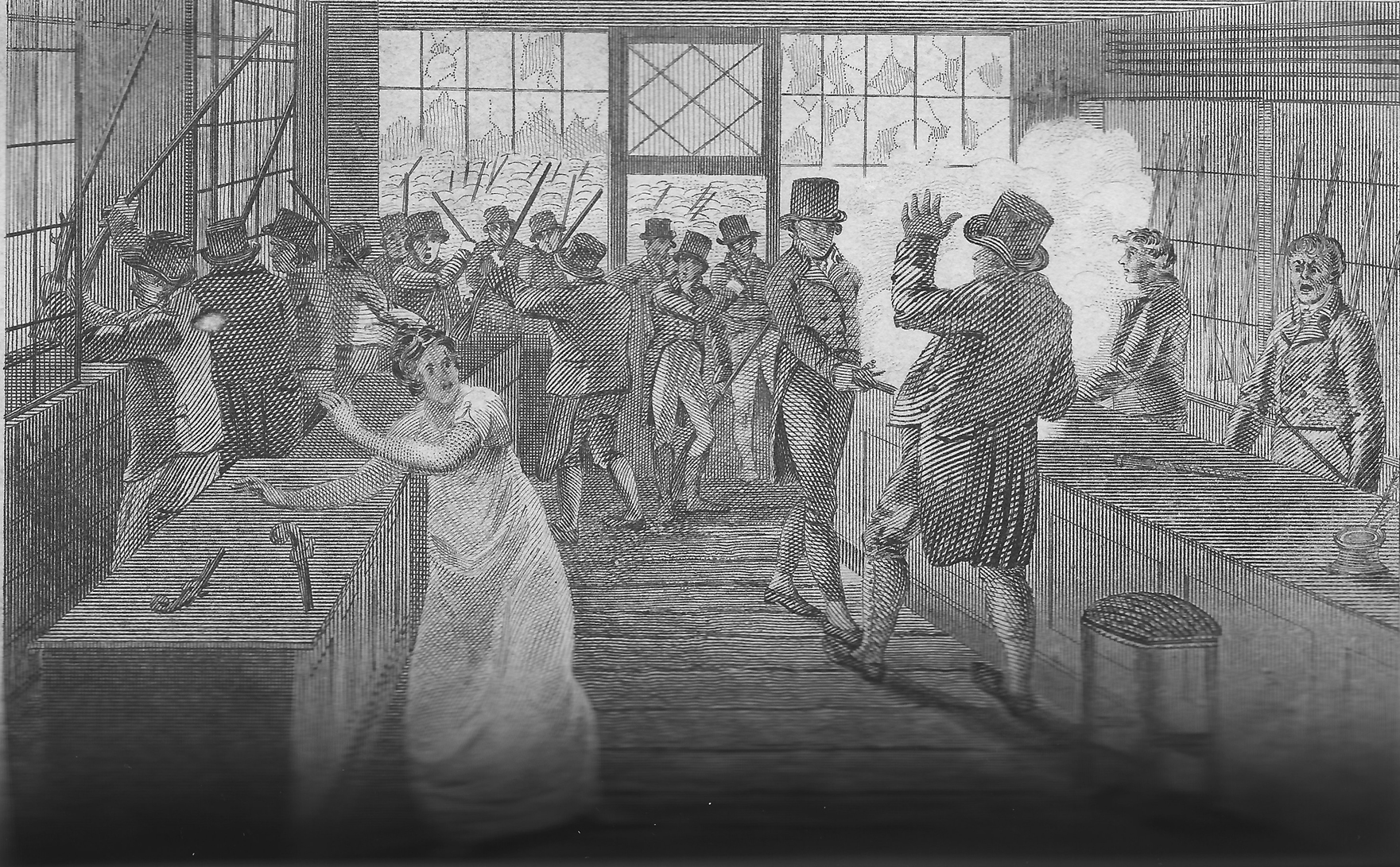

The Cato Street Conspiracy was an attempt to murder all the British cabinet ministers and Prime Minister Lord Liverpool (1770 – 1828) in 1820.

The name comes from the meeting place near Edgware Road in London.

The police had an informer.

The plotters fell into a police trap.

Thirteen were arrested, while one policeman, Richard Smithers, was killed.

Five conspirators were executed.

Five others were transported to Australia.

How widespread the Cato Street conspiracy was is uncertain.

It was a time of unrest.

Rumours abounded.

Malcolm Chase noted that:

“London’s Irish community and a number of trade societies, notably shoemakers, were prepared to lend support, while unrest and awareness of a planned rising were widespread in the industrial north and on Clydeside.“

The conspirators were called the Spencean Philanthropists, a group taking their name from the British radical speaker Thomas Spence (1750 – 1814).

The group was known for being a revolutionary organization, involved in unrest and propaganda and plotting the overthrow of the government.

Some of them, particularly Arthur Thistlewood (1774 – 1820), had been involved with the Spa Fields Riots (15 November and 2 December 1816), which demanded universal (male) suffrage, annual parliaments, secret ballots and redistribution of land in a time of mass unemployment and distress in an ailing economy.

Thistlewood came to dominate the group with George Edwards as his second in command.

Edwards was a police spy.

Most of the members were angered by the Six Acts and the Peterloo Massacre (16 August 1819), as well as with the economic depression and political repression of the time.

The six acts were:

- The Training Prevention Act, now known as the Unlawful Drilling Act of 1819, made any person attending a meeting for the purpose of receiving training or drill in weapons liable to arrest and transportation (penal relocation). More simply stated, military training of any sort was to be conducted only by municipal bodies and above.

- The Seizure of Arms Act gave local magistrates the powers, within the disturbed counties, to search any private property for weapons and seize them and arrest the owners.

- The Misdemeanours Act attempted to increase the speed of the administration of justice by reducing the opportunities for bail and allowing for speedier court processing.

- The Seditious Meetings Act required the permission of a sheriff or magistrate in order to convene any public meeting of more than 50 people if the subject of that meeting was concerned with “church or state” matters. Additional people could not attend such meetings unless they were inhabitants of the parish.

- The Blasphemous and Seditious Libels Act (or Criminal Libel Act) toughened the existing laws to provide for more punitive sentences for the authors of such writings. The maximum sentence was increased to 14 years’ penal relocation.

- The Newspaper and Stamp Duties Act extended and increased taxes to cover those publications which had escaped duty by publishing opinion and not news. Publishers were also required to post a bond for their behaviour.

The conspirators planned to assassinate the cabinet which was supposed to be together at a dinner.

They would then seize key buildings, overthrow the government and establish a “Committee of Public Safety” to oversee a radical revolution.

According to the prosecution at their trial, they had intended to form a provisional government headquartered in the Mansion House.

Hard economic times encouraged social unrest.

The end of the Napoleonic Wars (1803 – 1815) further worsened the economy and saw the return of job-seeking veterans.

King George III’s (1738 – 1820) death on 29 January 1820 created a new governmental crisis.

In a meeting held on 22 February, George Edwards suggested that the group could exploit the political situation and kill all the cabinet ministers after invading the fictitious cabinet dinner at the home of Lord Harrowby (1762 – 1847), Lord President of the Council, armed with pistols and grenades.

Edwards even provided funds to help arm the conspirators.

Thistlewood thought the act would trigger a massive uprising against the government.

James Ings, a coffeeshop keeper and former butcher, later announced that he would have decapitated all the cabinet members and taken two heads to exhibit on Westminster Bridge.

Thistlewood spent the next hours trying to recruit more men for the attack.

Twenty-seven men joined the effort.

When Jamaican-born William Davidson (1881 – 1920), who had worked for Lord Harrowby, went to find more details about the cabinet dinner, a servant in Lord Harrowby’s house told him that his master was not at home.

When Davidson told this to Thistlewood, he refused to believe it and demanded that the operation commence at once.

Above: English conspirator William Davidson

John Harrison rented a small house in Cato Street as the base of operations.

However, Edwards kept the police fully informed.

Some of the other members had suspected Edwards, but Thistlewood had made him his top aide.

Edwards had presented the idea with the full knowledge of the Home Office (responsible for immigration, security, law and order), which had also put the advertisement about the supposed dinner in The New Times.

When he reported that his would-be-comrades would be ready to follow his suggestion, the Home Office decided to act.

On 23 February, Richard Birnie (1760 – 1832), Bow Street magistrate, and George Ruthven, another police spy, went to wait at a public house on the other side of the street of the Cato Street building with twelve officers of the Bow Street Runners (London’s first professional police force).

Birnie and Ruthven waited for the afternoon because they had been promised reinforcements from the Coldstream Guards, under the command of Captain FitzClarence (1799 – 1854).

Thistlewood’s group arrived during that time.

At 7:30 pm, the Bow Street Runners decided to apprehend the conspirators themselves.

In the resulting brawl, Thistlewood killed Bow Street Runner Richard Smithers with a sword.

Some conspirators surrendered peacefully, while others resisted forcefully.

William Davidson was captured.

Thistlewood, Robert Adams, John Brunt and John Harrison slipped out through the back window, but were arrested a few days later.

The charges:

1. Conspiring to devise plans to subvert the Constitution.

2. Conspiring to levy war, and subvert the Constitution.

3. Conspiring to murder divers of the Privy Council.

4. Providing arms to murder divers of the Privy Council.

5. Providing arms and ammunition to levy war and subvert the Constitution.

6. Conspiring to seize cannon, arms and ammunition to arm themselves, and to levy war and subvert the Constitution.

7. Conspiring to burn houses and barracks, and to provide combustibles for that purpose.

8. Preparing addresses and correspondence. containing incitements to the King’s subjects to assist in levying war and subverting the Constitution.

9. Preparing an address to the King’s subjects, containing therein that their tyrants were destroyed, and to incite them to assist in levying war, and in subverting the Constitution.

10. Assembling themselves with arms, with intent to murder divers of the Privy Council, and to levy war, and subvert the Constitution.

11. Levying war.

During the trial, the defence argued that the statement of Edwards, a government spy, was unreliable and he was therefore never called to testify.

Police persuaded two of the men, Robert Adams and John Monument, to testify against other conspirators in exchange for dropped charges.

On 28 April most of the accused were sentenced to be hanged, drawn and quartered for high treason.

All sentences were later commuted, at least in respect of this medieval form of execution, to hanging and beheading.

The death sentences of Charles Cooper, Richard Bradburn, John Harrison, James Wilson and John Strange were commuted to transportation for life.

Arthur Thistlewood, Richard Tidd, James Ings, William Davidson and John Brunt were hanged at Newgate Prison on the morning of 1 May 1820 in front of a crowd of many thousands, some having paid as much as three guineas for a good vantage point from the windows of houses overlooking the scaffold.

Infantry were stationed nearby, out of sight of the crowd, two troops of Life Guards were present, and eight artillery pieces were deployed commanding the road at Blackfriars Bridge.

Large banners had been prepared with a painted order to disperse.

These were to be displayed to the crowd if trouble caused the authorities to invoke the Riot Act.

However, the behaviour of the multitude was “peaceable in the extreme“.

The hangman was John Foxton (1769 – 1829).

After the bodies had hung for half an hour, they were lowered one at a time and an unidentified individual in a black mask decapitated them against an angled block with a small knife.

Each beheading was accompanied by shouts, booing and hissing from the crowd and each head was displayed to the assembled spectators, declaring it to be the head of a traitor, before placing it in the coffin with the remainder of the body.

The British government used the incident to justify the Six Acts that had been passed two months before.

However, in the House of Commons Matthew Wood MP (1768 – 1843) accused the government of purposeful entrapment of the conspirators to smear the campaign for parliamentary reform.

Although there is evidence that Edwards did incite certain actions of the conspirators, the idea is not supported by modern historians.

However, the otherwise pro-government newspaper The Observer ignored the order of the Lord Chief Jûstice Sir Charles Abbott (1762 – 1832) not to report the trial before the sentencing.

Tuesday 23 February 1836, San Antonio, Texas

After a failed attempt by France to colonize Texas in the late 17th century, Spain developed a plan to settle the region.

On its southern edge, along the Medina and Nueces Rivers, Spanish Texas was bordered by the province of Coahuila.

On the east, Texas bordered Louisiana.

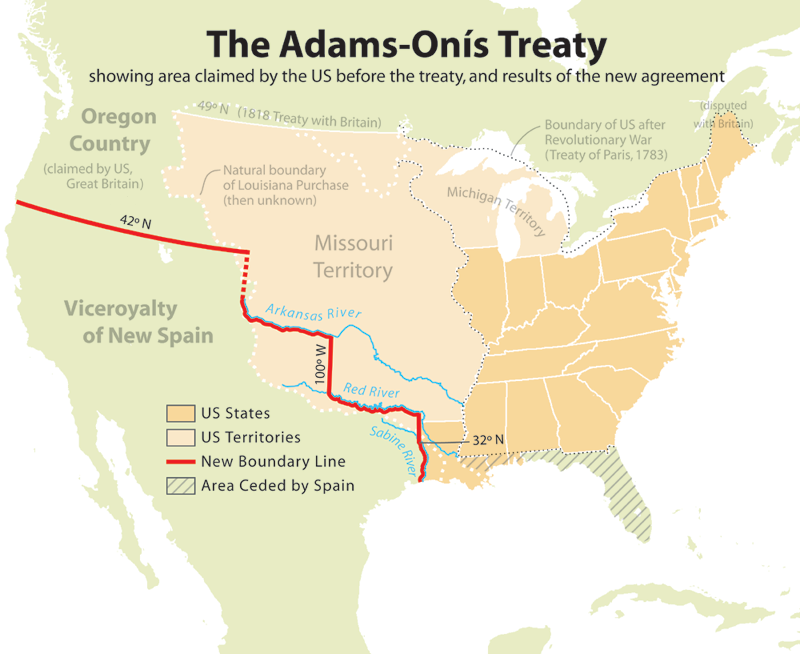

Following the Louisiana Purchase of 1803, the United States also claimed the land west of the Sabine River, all the way to the Rio Grande.

From 1812 to 1813 anti-Spanish republicans and US filibusters (unauthorized military invaders) rebelled against the Spanish Empire in what is known today as the Gutiérrez – Magee Expedition (1812 – 1813) during the Mexican War of Independence (1810 – 1821).

They won battles in the beginning and captured many Texas cities from the Spanish that led to a declaration of independence of the state of Texas as part of the Mexican Republic on 17 April 1813.

The new Texas government and army met their doom in the Battle of Medina on 18 August 1813, 20 miles south of San Antonio, where 1,300 of the 1,400 rebel army were killed in battle or executed shortly afterwards by royalist soldiers.

It was the deadliest single battle in Texas history.

300 republican government officials in San Antonio were captured and executed by the Spanish royalists shortly after the battle.

Antonio López de Santa Anna, future President of Mexico, fought in this battle as a royalist and followed his superiors’ orders to take no prisoners.

Another interesting note is two founding fathers of the Republic of Texas and future signers of the Texas Declaration of Independence in 1836, José Antonio Navarro and José Francisco Ruiz, took part in the Gutiérrez – Magee Expedition.

Although the United States officially renounced that claim as part of the Transcontinental Treaty (Adams – Otis Treaty) with Spain in 1819, many Americans continued to believe that Texas should belong to their nation, and over the next decade the United States made several offers to purchase the region.

Following the Mexican War of Independence, Texas became part of Mexico.

Under the Constitution of 1824, which defined Mexico as a federal republic, the provinces of Texas and Coahuila were combined to become the state Coahuila y Tejas.

Texas was granted only a single seat in the state legislature, which met in Saltillo, hundreds of miles away.

After months of grumbling by Tejanos (Mexican-born residents of Texas) outraged at the loss of their political autonomy, state officials agreed to make Texas a department of the new state, with a de facto capital in San Antonio de Béxar.

Texas was very sparsely populated, with fewer than 3,500 residents, and only about 200 soldiers, which made it extremely vulnerable to attacks by native tribes and American filibusters.

In the hopes that an influx of settlers could control the Indian raids, the bankrupt Mexican government liberalized immigration policies for the region.

Finally able to settle legally in Texas, Anglos from the United States soon vastly outnumbered the Tejanos.

Most of the immigrants came from the southern United States.

Many were slave owners and most brought with them significant prejudices against other races, attitudes often applied to the Tejanos.

Mexico’s official religion was Roman Catholicism, yet the majority of the immigrants were Protestants who distrusted Catholics.

Mexican authorities became increasingly concerned about the stability of the region.

The colonies teetered at the brink of revolt in 1829, after Mexico abolished slavery.

In response, Mexican President Anastasio Bustamante implemented the Laws of 6 April 1830, which, among other things, prohibited further immigration to Texas from the United States, increased taxes and reiterated the ban on slavery.

Settlers simply circumvented or ignored the laws.

By 1834, an estimated 30,000 Anglos lived in Coahuila y Tejas, compared to only 7,800 Mexican-born residents.

By the end of 1835, almost 5,000 enslaved Africans and African Americans lived in Texas, making up 13% of the non-Indigenous population.

In 1832, Santa Anna led a revolt to overthrow Bustamante.

Texians (English-speaking settlers) used the rebellion as an excuse to take up arms.

By mid-August, all Mexican troops had been expelled from east Texas.

Buoyed by their success, Texians held two political conventions to persuade Mexican authorities to weaken the Laws of 6 April 1830.

In November 1833, the Mexican government attempted to address some of the concerns, repealing some sections of the law and granting the colonists further concessions, including increased representation in the state legislature.

Stephen F. Austin, who had brought the first American settlers to Texas, wrote to a friend that “Every evil complained of has been remedied.”

Mexican authorities were quietly watchful, concerned that the colonists were maneuvering towards secession.

Santa Anna soon revealed himself to be a centralist, transitioning the Mexican government to a centralized government.

In 1835, the 1824 Constitution was overturned.

State legislatures were dismissed, militias disbanded.

Federalists throughout Mexico were appalled.

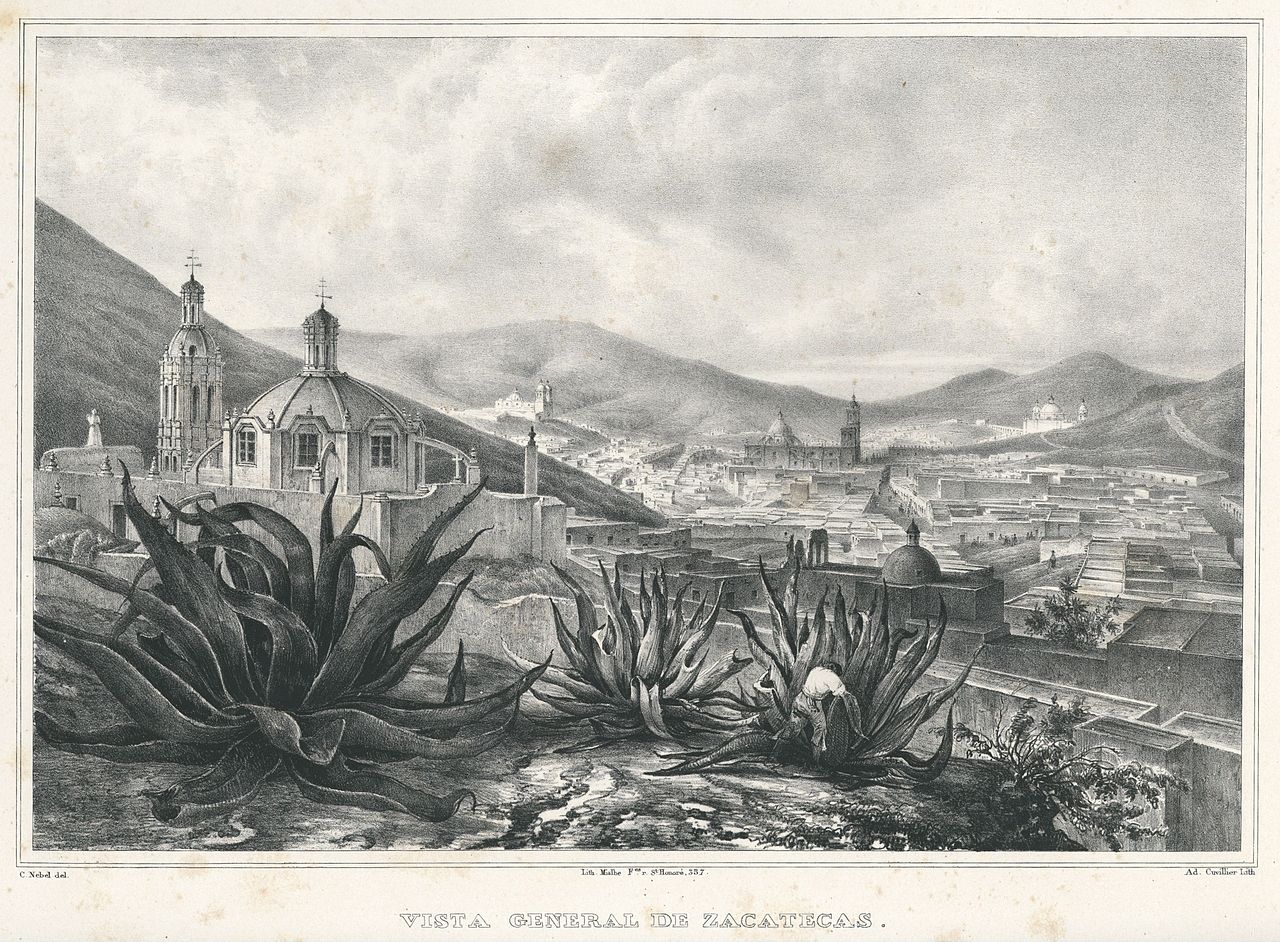

Citizens in the states of Oaxaca and Zacatecas took up arms.

The governor of Zacatecas himself, Francisco Garcia Salinas, led an army of about 4,000 men against the government.

To end the rebels, President Santa Anna in person went to fight, leaving the presidency in charge of General Miguel Barragán.

García Salinas was defeated in the Battle of Zacatecas (1835).

Santa Anna allowed his troops to loot the city, then, and as punishment for the rebellion, the state of Zacatecas lost part of its territory, which formed the state of Aguascalientes.

This military action removed the final obstacles to centralism and led to the constitution of 30 December1836, known as Siete Leves, which limited the right to vote and removed the political and financial autonomy previously held by Mexican states.

After Santa Anna’s troops subdued the rebellion in Zacatecas in May, he gave his troops two days to pillage the city.

Over 2,000 noncombatants were killed.

The governor of Coahuila y Tejas, Agustin Viesca, refused to dissolve the Legislature, instead ordering that the session reconvene in Béxar, further from the influence of the Mexican army.

Although prominent Tejano Juan Seguin raised a militia company to assist the governor, the Béxar ayuntamiento (city council) ordered him not to interfere.

Viesca was arrested before he reached Texas.

Public opinion in Texas was divided.

Editorials in the United States began advocating complete independence for Texas.

After several men staged a minor revolt against customs duties in Anahuac in June, local leaders began calling for a public meeting to determine whether a majority of settlers favored independence, a return to federalism, or the status quo.

Although some leaders worried that Mexican officials would see this type of gathering as a step towards revolution, by the end of August most communities had agreed to send delegates to the Consultation (provisional government of Mexican Texas: 1835 – 1836), scheduled for 15 October.

As early as April 1835, military commanders in Texas began requesting reinforcements, fearing the citizens would revolt.

Mexico was ill-prepared for a large civil war, but continued unrest in Texas posed a significant danger to the power of Santa Anna and of Mexico.

If the people of Coahuila also took up arms, Mexico faced losing a large portion of its territory.

Without the northeastern province to act as a buffer, it was likely that United States influence would spread, and the Mexican territories of Nuevo Mexico and Alta California would be at risk of future American encroachment.

Santa Anna had no wish to tangle with the United States and he knew that the unrest needed to be subdued before the United States could be convinced to become involved.

In early September, Santa Anna ordered his brother-in-law, General Martin Perfecto de Cos (1800 – 1854), to lead 500 soldiers to Texas to quell any potential rebellion.

Cos and his men landed at the port of Copano on 20 September.

Austin called on all municipalities to raise militias to defend themselves.

In 1835, as the Mexican government began to shift away from a federalist model, violence erupted in several Mexican states, including the border region of Mexican Texas.

By the end of the year, Texian forces had expelled all Mexican soldiers from the area.

In Mexico City, President Antonio López de Santa Anna had begun gathering an army to retake Texas.

When Mexican troops departed San Antonio de Béxar (now San Antonio, Texas, USA), Texian soldiers established a garrison at the Alamo Mission, a former Spanish religious outpost which had been converted to a makeshift fort.

Described by Santa Anna as an “irregular fortification hardly worthy of the name“, the Alamo had been designed to withstand an attack by native tribes, not an artillery-equipped army.

The complex sprawled across 3 acres (1.2 ha), providing almost 1,320 feet (400 m) of perimeter to defend.

An interior plaza was bordered on the east by the chapel and to the south by a one-story building known as the Low Barracks.

A wooden palisade stretched between these two buildings.

The two-story Long Barracks extended north from the chapel.

At the northern corner of the east wall stood a cattle pen and horse corral.

The walls surrounding the complex were at least 2.75 feet (0.84 m) thick and ranged from 9–12 ft (2.7–3.7 m) high.

On 11 February, the commander of the Alamo, Colonel James C. Neill (1788 – 1848), left the Alamo, likely to recruit additional reinforcements and gather supplies.

In his absence, the garrison was jointly commanded by newcomers William B. Travis (1809 – 1836) — a regular army officer — and James Bowie (1796 – 1836), who had commanded a volunteer company.

As the Texians struggled to find men and supplies, Santa Anna’s army began marching north.

On 12 February they crossed the Rio Grande.

On 16 February and 18 February, local resident Ambrosio Rodriguez warned his good friend William Barret Travis that their relatives further south claimed that Santa Anna was on the march towards Bexar.

Two days later Juan Seguin’s scout Blas Maria Herrera reported that the vanguard of the Mexican army had crossed the Rio Grande.

There had been many rumors of Santa Anna’s imminent arrival, but Travis ignored them.

For several hours that night a council of war held at the Alamo argued over whether to believe the rumours.

Travis was convinced that the Mexican army would not arrive in Béxar until at least mid-March.

He, and others in the Texian army thought Santa Anna would not march until spring, when the grass had begun to grow again.

They overlooked the fact that mesquite grass sprouted earlier than normal grass.

Travis had also assumed that Santa Anna would not have begun gathering troops for an invasion of Texas until after he had learned of Cos’s defeat.

The Texians did not realize that Santa Anna had begun preparations for an invasion months before.

Despite the Texian disbelief, by the evening of 20 February many of the residents of Béxar began to pack their belongings in preparation for leaving.

The next day, fifteen of the Tejano volunteers at the Alamo resigned.

Seguin had asked Travis to release the men so that they could help evacuate their families, who were in the path Santa Anna would take to reach Béxar.

Santa Anna had crossed the Rio Grande on 16 February.

The next night, his army camped on the Nueces River, 119 miles (192 km) from Bexar.

Texians had previously burned the bridge over the Nueces, forcing the Mexicans to build a makeshift structure of branches and dirt in the pouring rain.

The delay was brief, and on 19 February the vanguard of the army camped along the Frio River, 68 miles (109 km) from Béxar.

The following day they reached Hondo, less than 50 miles (80 km) away.

By 1:45 pm on 21 February Santa Anna and his vanguard had reached the banks of the Medina River, 25 miles (40 km) from Béxar.

Waiting there were dragoons under Colonel Ramirez y Sesma, who had arrived the previous evening.

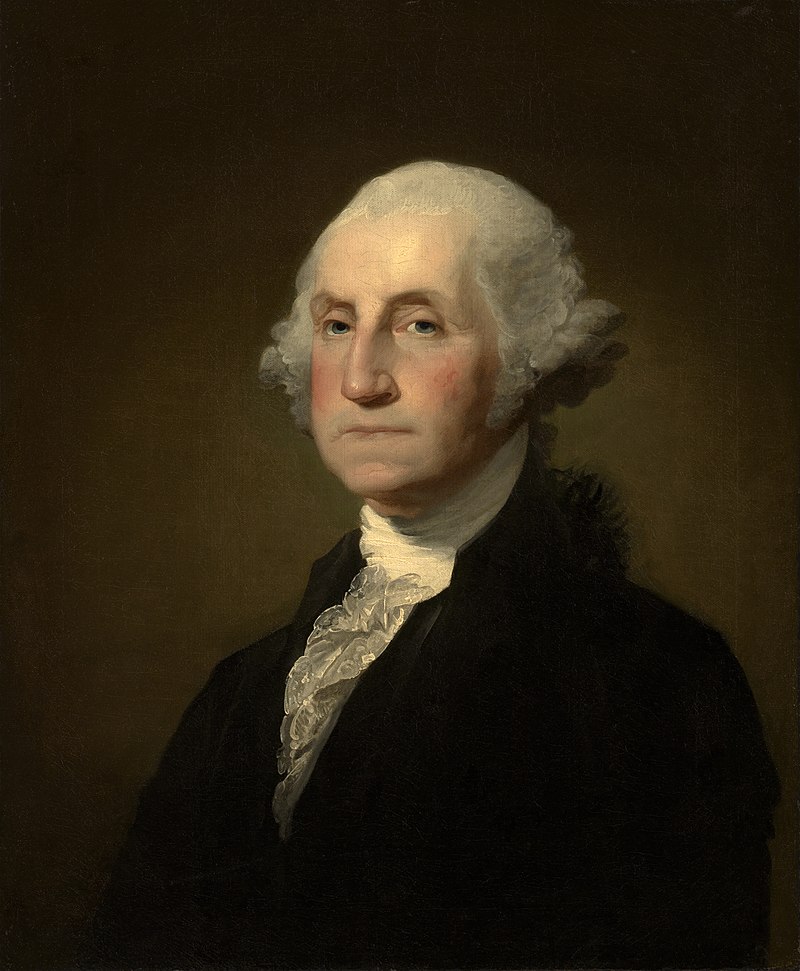

With no idea that the Mexican army was so close, all but ten members of the Alamo garrison joined about 2,000 Bexar residents at a fiesta to celebrate George Washington’s birthday.

Centralists in Bexar soon alerted Santa Anna to the party, and he ordered General Ramirez y Sesma to lead a cavalry force to take the Alamo while the garrison celebrated elsewhere.

The raid had to be called off when sudden rains made the Medina unfordable.

The next night, Santa Anna and his army camped at Leon Creek, 8 miles (13 km) west of what is now downtown San Antonio.

In the early hours of 23 February, residents began fleeing Béxar, fearing the Mexican army’s imminent arrival.

Although unconvinced by the reports, Travis stationed a soldier in the San Fernando Church bell tower — the highest location in town — to watch for signs of an approaching force.

Travis then sent Captain Philip Dimitt (1801 – 1841) and Lieutenant Benjamin Noble to scout for the Mexican army’s location.

At approximately 2:30 that afternoon the church bell began to ring.

The soldier stationed in the tower claimed to have seen flashes in the distance.

Dimitt and Noble had not returned, so Travis sent Dr. James Sutherland and John W. Smith (1792 – 1845) on horseback to scout the area.

Smith and Sutherland spotted members of the Mexican cavalry within 1.5 miles (2.4 km) of the town and returned to Béxar at a run.

According to later reports from Santa Anna, the cavalry, under General Joaquin Ramirez y Sesma, were supposed to execute a surprise attack on the morning of 23 February.

Historian Thomas Ricks Lindley concluded that Sesma’s troops had captured a Texian spy, Trinidad Coy, who lied about a Texian ambush further ahead, prompting Sesma to halt at 7 a.m. and wait for reinforcements.

Historian Lon Tinkle speculated that the combination of the church bell ringing and the sight of the two Texian scouts led Sesma to believe that the Texians were planning an assault on the cavalry.

At this point there were approximately 156 effective Texian soldiers in the Alamo, with another 14 in the hospital.

The men were completely unprepared for the arrival of the Mexican army and had no food in the mission.

The men quickly herded cattle in the Alamo and scrounged for food in nearby houses.

They were able to gather enough beef and corn into the Alamo to last a month.

The Alamo garrison also had a large supply of captured Mexican muskets, with over 19,000 paper cartridges, but only a limited supply of powder for the artillery.

Several members of the garrison dismantled the blacksmith shop of Antonio Saez and moved much of the material into the Alamo.

A few members of the garrison brought their families into the Alamo to keep them safe.

Among these was Alamaron Dickinson, who fetched his wife Susanna (1813 – 1883) and their daughter Angelina, and Bowie, who brought his deceased wife’s cousins, Gertrudis Navarro and Juana Navarro Alsbury (1812 – 1888) and Alsbury’s young son into the fort.

It is likely that Navarro and Alsbury also brought their family’s servants, Sam and Bettie.

While the bulk of the garrison prepared for the attack, a few Texians remained in Béxar and raised a flag in the middle of Military Plaza.

According to historian J.R. Edmondson:

“The flag was a variation of the Mexican tricolor with two stars, representing the separated states of Texas and Coahuila, gleaming from the white center bar.”

Within an hour the first of the Mexican cavalry, commanded by Colonel Jose Vicente Minon, entered Béxar.

The Texians lowered their flag and brought it into the Alamo.

As the Mexican cavalry approached, Travis dispatched a man named John Johnson to ask Colonel James Fannin (1804 – 1836), 100 miles (160 km) southeast, to send reinforcements immediately.

Travis then sent Smith and Sutherland to bring a message to the alcade at Gonzales, 70 miles (110 km) away.

The note to Gonzales read:

“The enemy in large force is in sight.

We want men and provisions.

Send them to us.

We have 150 men and are determined to defend the Alamo to the last.”

By late afternoon, Béxar was occupied by about 1,500 Mexican troops, who quickly raised a blood-red flag signifying “no quarter“.

Soon after, a Mexican bugler sounded the request for parley.

Travis ordered the Alamo’s 18-pounder cannon fired.

The Mexican army responded with four balls from 7-inch howitzers.

The balls hit the interior of the Alamo but caused no damage or injuries.

Santa Anna later reported that the initial Texian cannon fire killed two Mexican soldiers and wounded eight others.

No other Mexican officer, however, reported fatalities from that day.

Bowie believed that Travis had acted hastily and sent Green B. Jameson to meet with Santa Anna.

Jameson carried a letter addressed to “the commander of the invading forces below Bejar” and signed “the commander of the volunteers of Bejar“.

Angry that Bowie presented himself as Santa Anna’s equal, the Mexican general refused to meet with Jameson, but allowed Colonel Juan Almonte (1803 – 1869) and Jose Bartres to parley.

Almonte later said that Jameson asked for an honorable surrender, but Bartres replied:

“I reply to you, according to the order of His Excellency, that the Mexican army cannot come to terms under any conditions with rebellious foreigners to whom there is no recourse left, if they wish to save their lives, than to place themselves immediately at the disposal of the Supreme Government from whom alone they may expect clemency after some considerations.“

Travis was angered that Bowie had acted unilaterally and sent his own emissary to the Mexican army.

He received the same response.

Bowie and Travis then mutually agreed to fire the cannon again.

By the time the parleys were over it was nightfall, and the firing ceased.

That evening the Mexicans erected an artillery battery near the Veramendi house.

Santa Anna also sent General Ventura Mora’s cavalry to circle to the north and east of the Alamo to prevent the arrival of Texian reinforcements.

According to Edmondson, the Texians sent a small party to forage that evening.

They returned with six pack mules and a prisoner, a Mexican soldier who would later be used to interpret Mexican bugle calls.

The Texians received one reinforcement that night, when one of Seguin’s men, Gregorio Esparza (1802 – 1836), arrived with his family.

Texian sentries refused to open the gate, but others helped the family climb through the window of the chapel.

Several other Texian soldiers were unable to make it into the Alamo.

Dimitt and Noble, who had been scouting for signs of the Mexican army, were told by a local that Bexar was surrounded, and they would be unable to re-enter the town.

Andrew Jackson Sowell (1815 – 1843) and Byrd Lockhart (1782 – 1839) had been out that morning looking for provisions.

On hearing that the Alamo was surrounded they left for their homes in Gonzales.

The Siege of the Alamo (23 February – 6 March 1836) describes the first thirteen days of the Battle of the Alamo.

On 23 February, Mexican troops under General Antonio López de Santa Anna entered San Antonio de Bexar and surrounded the Alamo Mission.

The Alamo was defended by a small force, led by William Barrett Travis and James Bowie, and included Davy Crockett (1786 – 1836).

Before beginning his assault on the Alamo, Santa Anna offered them one last chance to surrender.

Travis replied by opening fire on the Mexican forces and, in doing so, effectively sealed their fate.

The siege ended when the Mexican Army launched an early morning assault on 6 March.

Almost all of the defenders were killed, although several civilians survived.

150 against an entire army.

Insanity.

Did they truly believe they could win against these odds?

Did they truly think that the loss of their lives made any difference in an outcome that would be determined not so much by the superiority of American soldiers but by the incompetent errors that would be committed by an overconfident vainglorious Mexican commander?

Scott became famous for freezing to death in Antarctica

Columbus made history thinking some island was India

General Custer’s a national hero for not knowing when to run

All of these men are famous

And they’re also very dumb

History is made by stupid people

Clever people wouldn’t even try

If you want a place in the history books

Then do something dumb before you die

Nobility are famous for no reason

Mary Antoinette enjoyed her cake

She caused a revolution when she would not share

And her husband lost his head for that mistake

The Hindenburg was a giant Zepplin

Its makers made a minor oversight

Before they filled it up with explosive gas

They should have fixed the no-smoking light

Above: Zeppelin Hindenburg (1936 – 1937)

‘Cause history is made by stupid people

Clever people wouldn’t even try

If you want a place in the history books

Then do something dumb before you die

Tally-ho! Tally-ho!

Our king and country’s honour we will save

Tally-ho! Tally-ho!

We’re marching into history and the grave

So if your son and daughter seem too lazy

Sitting there watching bad TV

Just remember you should be quite grateful

At least they are not making history

‘Cause history is made by stupid people

Clever people wouldn’t even try

If you want a place in the history books

Then do something dumb before you die

Do something dumb before you die

Do something dumb before you die

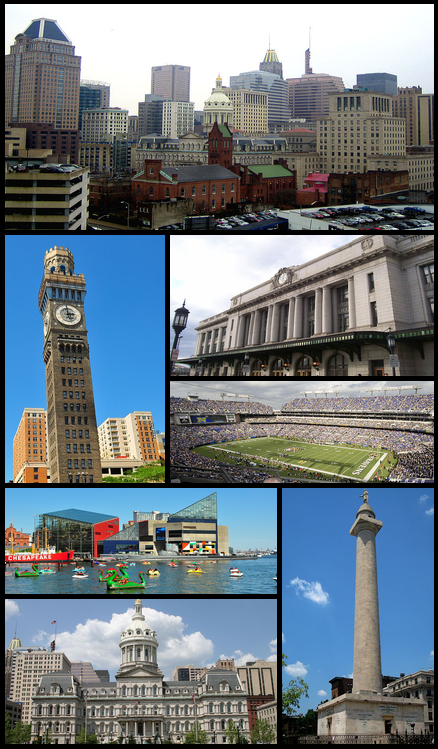

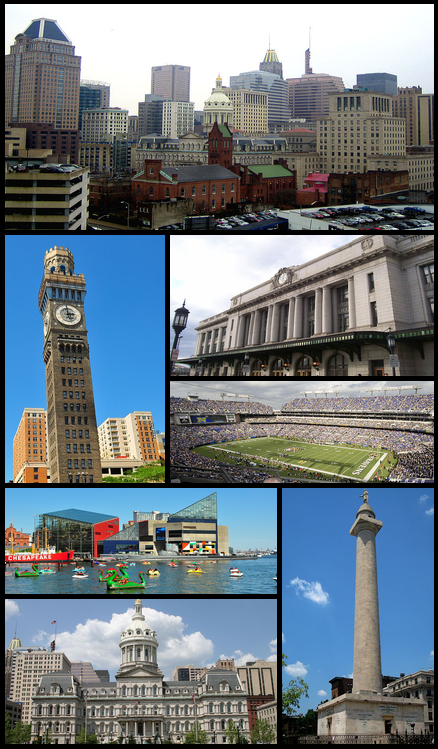

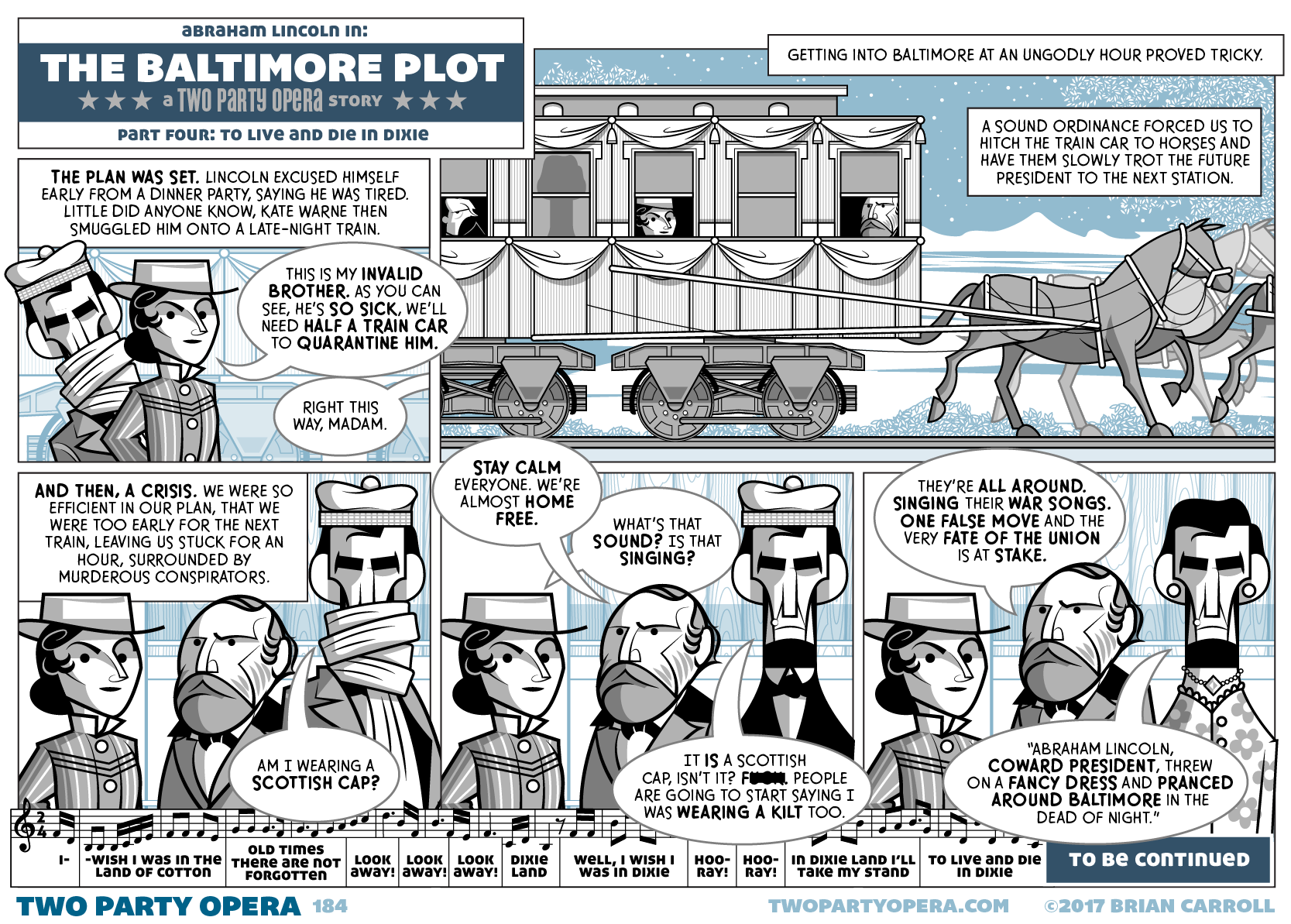

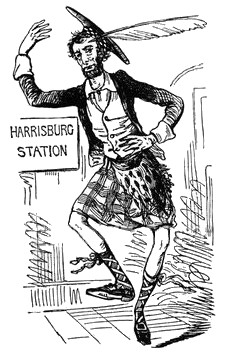

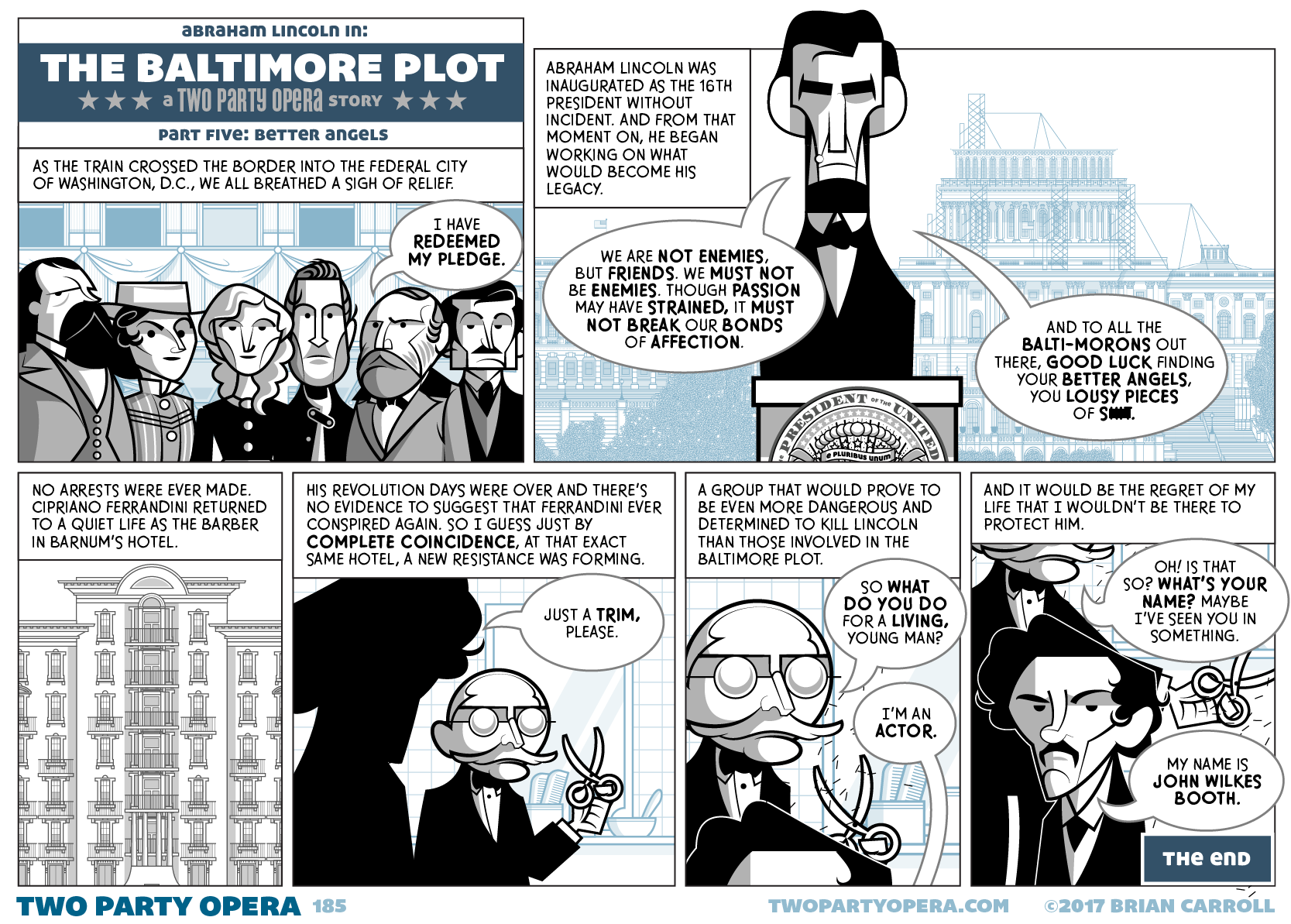

Saturday 23 February 1861, Baltimore, Maryland

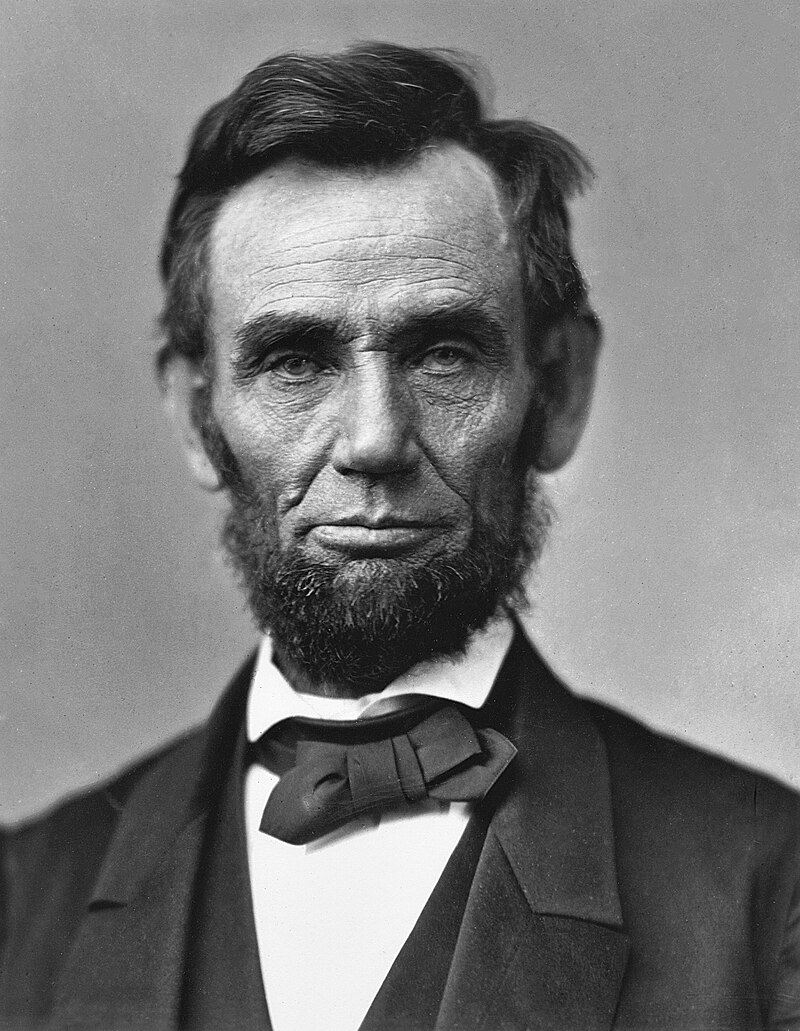

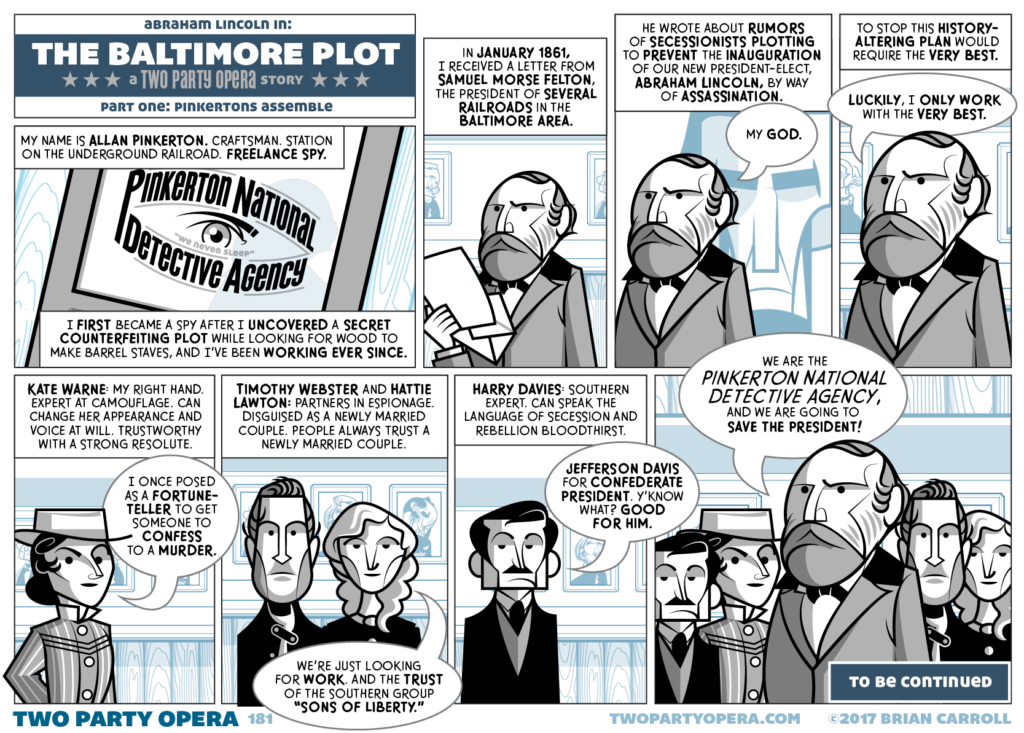

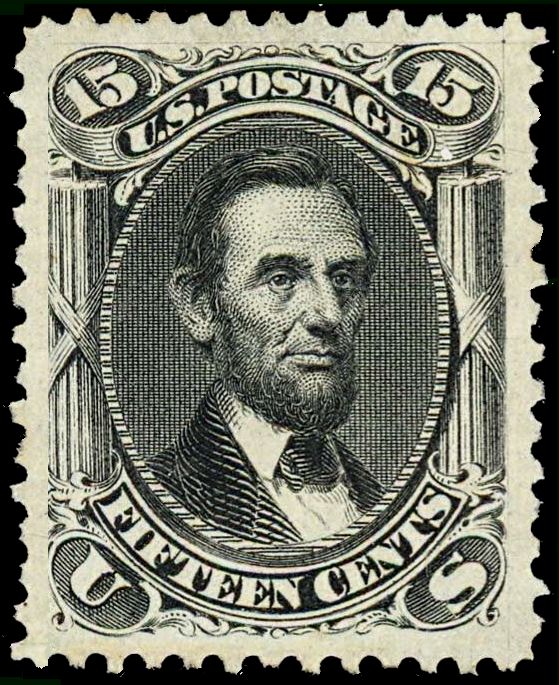

The Baltimore Plot was a conspiracy in late February 1861 to assassinate President-elect Abraham Lincoln en route to his Inauguration.

Allan Pinkerton, founder of the Pinkerton National Detective Agency, played a key role by managing Lincoln’s security throughout the journey.

Though scholars debate whether or not the threat was real, clearly Lincoln and his advisors believed that there was a threat and took actions to ensure his safe passage through Baltimore, Maryland.

On 6 November 1860, Lincoln was elected as the 16th President of the United States, a Republican, and the first to be elected from that party.

As he awaited the outcome of the voting on election night, 6 November 1860, Abraham Lincoln sat expectantly in the Springfield telegraph office.

The results came in around 2 a.m.:

Lincoln had won.

Even as jubilation erupted around him, he calmly kept watch until the results came in from Springfield, confirming that he had carried the town he had called home for a quarter century.

Only then did he return home to wake Mary Todd Lincoln, exclaiming to his wife:

“Mary, Mary, we are elected!”

By New Year Day’s 1861, he was already beleaguered by the sheer volume of correspondence reaching his desk in Springfield.

On one occasion he was spotted at the post office filling “a good sized market basket” with his latest batch of letters, and then struggling to keep his footing as he navigated the icy streets.

Soon, Lincoln took on an extra pair of hands to assist with the burden, hiring John Nicolay, a bookish young Bavarian immigrant, as his private secretary.

Nicolay was immediately troubled by the growing number of threats that crossed Lincoln’s desk.

“His mail was infested with brutal and vulgar menace, and warnings of all sorts came to him from zealous or nervous friends,” Nicolay wrote.

“But he had himself so sane a mind, and a heart so kindly, even to his enemies, that it was hard for him to believe in political hatred so deadly as to lead to murder.”

It was clear, however, that not all the warnings could be brushed aside.

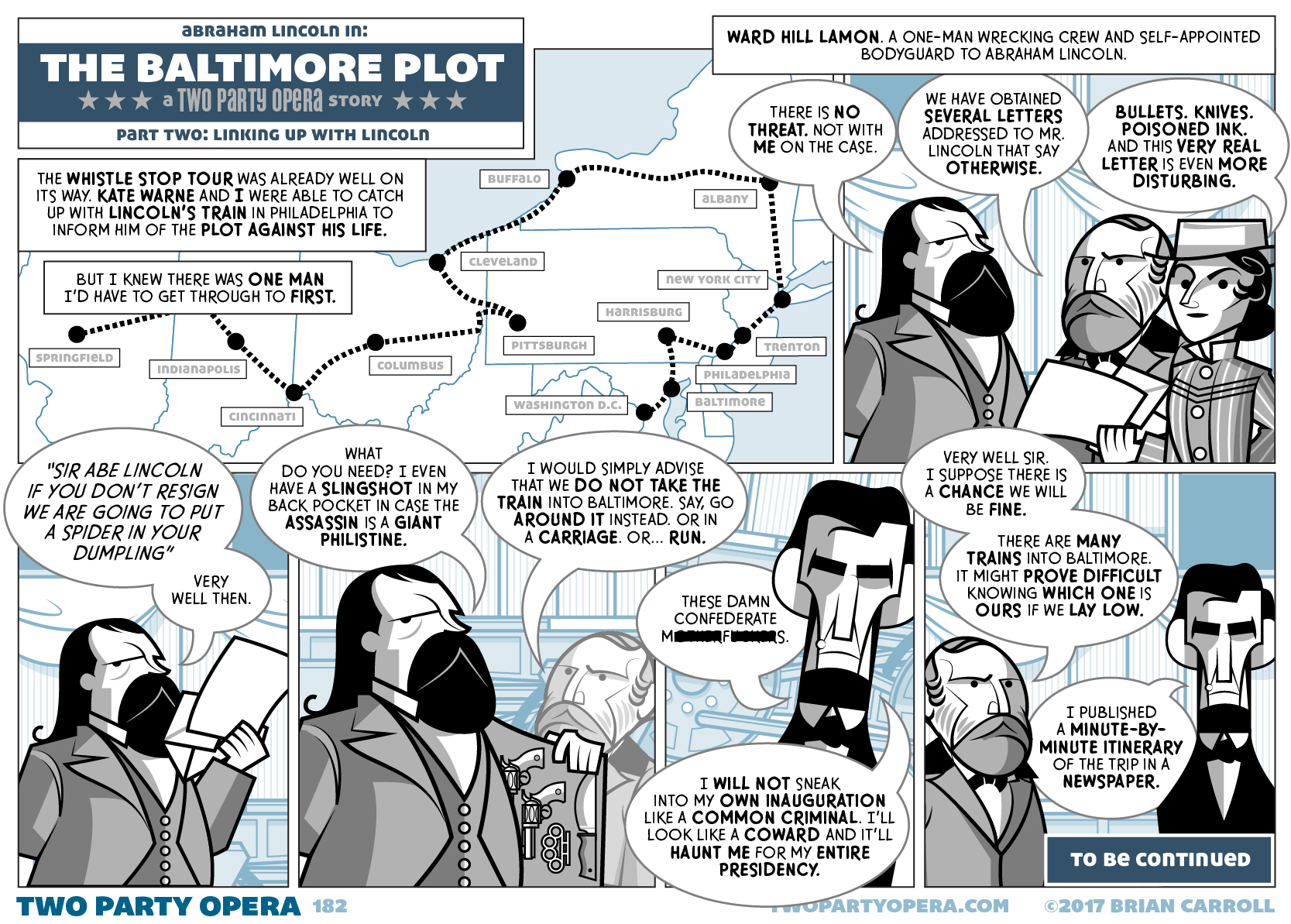

In the coming weeks, the arduous task of planning Lincoln’s railway journey to his Inauguration in the nation’s capital on 4 March would present daunting logistical and security challenges.

The task would prove all the more formidable, because Lincoln insisted that he utterly disliked “ostentatious display and empty pageantry”, and would make his way to Washington without a military escort.

Far from Springfield, in Philadelphia, at least one railway executive — Samuel Morse Felton, president of the Philadelphia, Wilmington and Baltimore Railroad — believed that the President-elect had failed to grasp the seriousness of his position.

Rumors had reached Felton — a stolid, bespectacled blueblood whose brother was president of Harvard at the time —that secessionists might be mounting a “deep-laid conspiracy to capture Washington, destroy all the avenues leading to it from the North, East, and West, and thus prevent the inauguration of Mr. Lincoln in the Capitol of the country.”

For Felton, whose track formed a crucial link between Washington and the North, the threat against Lincoln and his government also constituted a danger to the railroad that had been his life’s great labour.

“I then determined”, Felton recalled later, “to investigate the matter in my own way.”

What was needed, he realized, was an independent operative who had already proven his mettle in the service of the railroads.

Snatching up his pen, Felton dashed off an urgent plea to “a celebrated detective, who resided in the West.”

Shortly after his election, many representatives of southern states made it clear that the Confederacy’s secession from the US was inevitable, which greatly increased tension across the nation.

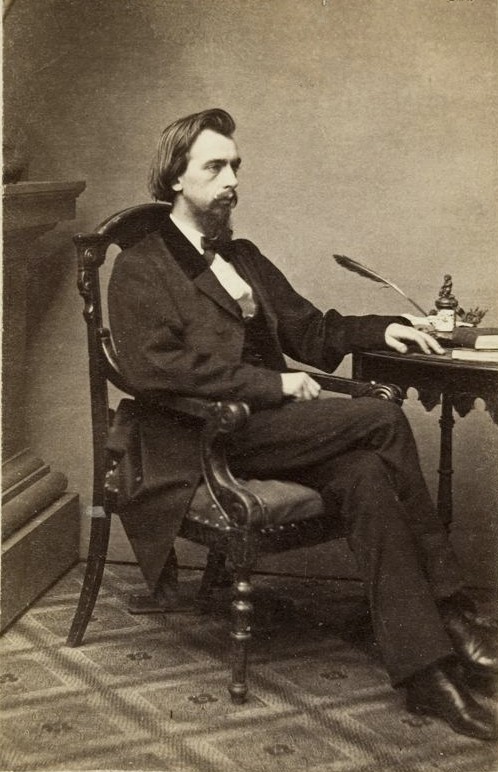

By the end of January, with barely two weeks remaining before Lincoln was to depart Springfield, Allan Pinkerton was on the case.

A Scottish immigrant, Pinkerton had started out as a cooper making barrels in a village on the Illinois prairies.

He had made a name for himself when he helped his neighbors snare a ring of counterfeiters, proving himself fearless and quick-witted.

He had gone on to serve as the first official detective for the city of Chicago, admired as an incorruptible lawman.

By the time Felton sought him out, the ambitious 41-year-old Pinkerton presided over the Pinkerton National Detective Agency.

Among his clients was the Illinois Central Railroad.

Felton’s letter landed on Pinkerton’s desk in Chicago on Saturday 19 January.

The detective set off within moments, reaching Felton’s office in Philadelphia only two days later.

Now, as Pinkerton settled into a chair opposite Felton’s broad mahogany desk, the railroad president outlined his concerns.

Shocked by what he was hearing, Pinkerton listened in silence.

Felton’s plea for help, the detective said, “aroused me to a realization of the danger that threatened the country, and I determined to render whatever assistance was in my power.”

Much of Felton’s line was on Maryland soil.

In recent days four more states — Mississippi, Florida, Alabama and Georgia — had followed the lead of South Carolina and seceded from the Union.

Louisiana and Texas would soon follow.

Maryland had been roiling with anti-Northern sentiment in the months leading up to Lincoln’s election, and at the very moment that Felton poured out his fears to Pinkerton, the Maryland legislature was debating whether to join the exodus.

If war came, Felton’s PW&B would be a vital conduit of troops and ammunition.

Both Felton and Pinkerton appear to have been blind, at this early stage, to the possibility of violence against Lincoln.

They understood that the secessionists sought to prevent the inauguration, but they had not yet grasped, as Felton would later write, that if all else failed, Lincoln’s life was to “fall a sacrifice to the attempt.”

If the plotters intended to disrupt Lincoln’s Inauguration — now only six weeks away — it was evident that any attack would come soon, perhaps even within days.

The detective departed immediately for “the seat of danger”— Baltimore.

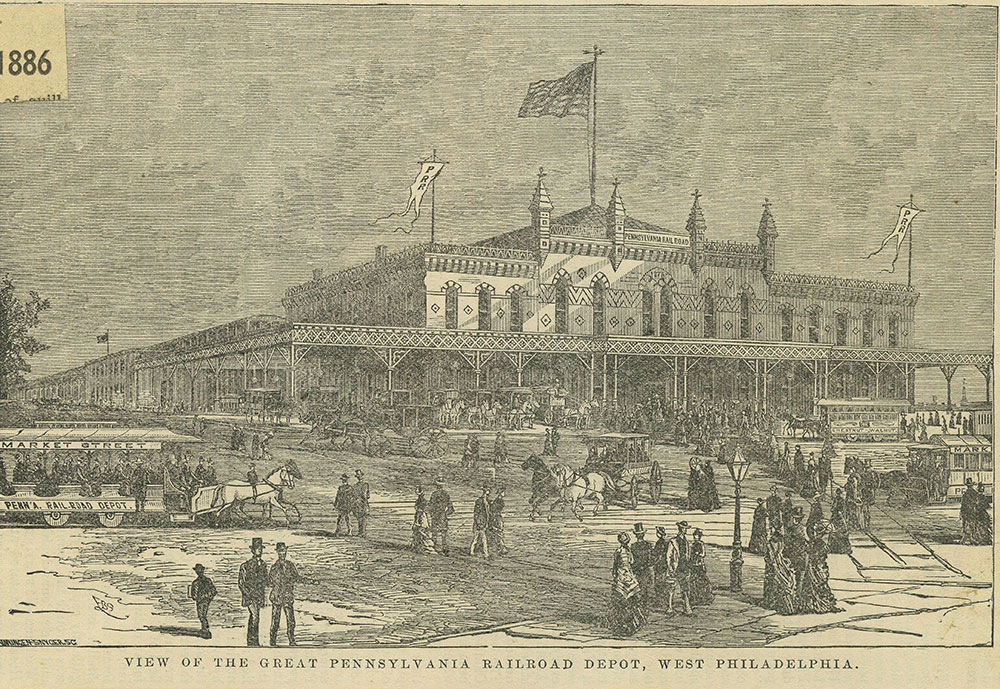

Virtually any route that the President-elect chose between Springfield and Washington would pass through the city.

A major port, Baltimore had a population of more than 200,000 — nearly twice that of Pinkerton’s Chicago — making it the nation’s 4th largest city, after New York, Philadelphia and Brooklyn, at the time a city in its own right.

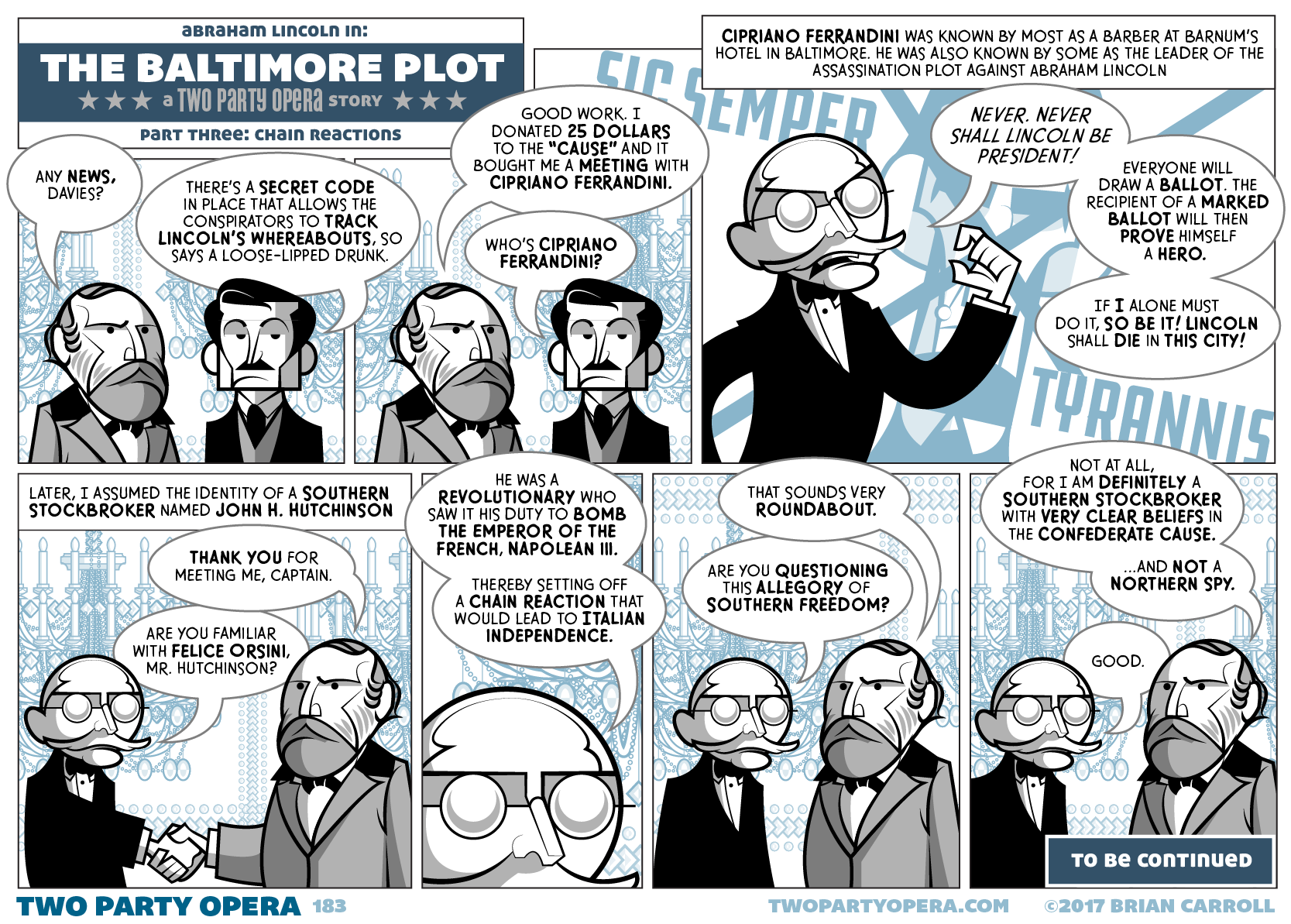

Pinkerton brought with him a crew of top agents, among them a new recruit, Harry Davies, a fair-haired young man whose unassuming manner belied a razor-sharp mind.

He had travelled widely, spoke many languages and had a gift for adapting himself to any situation.

Best of all from Pinkerton’s perspective, Davies possessed “a thorough knowledge of the South, its localities, prejudices, customs and leading men, which had been derived from several years residence in New Orleans and other Southern cities.”

Pinkerton arrived in Baltimore during the first week of February, taking rooms at a boarding house near the Camden Street train station.

He and his operatives fanned out across the city, mixing with crowds at saloons, hotels and restaurants to gather intelligence.

“The opposition to Mr. Lincoln’s Inauguration was most violent and bitter,” he wrote, “and a few days’ sojourn in this city convinced me that great danger was to be apprehended.”

Pinkerton decided to set up a cover identity as a newly arrived Southern stockbroker, John H. Hutchinson.

It was a canny choice, as it gave him an excuse to make himself known to the city’s businessmen, whose interests in cotton and other Southern commodities often gave a fair index of their political leanings.

In order to play the part convincingly, Pinkerton hired a suite of offices in a large building at 44 South Street.

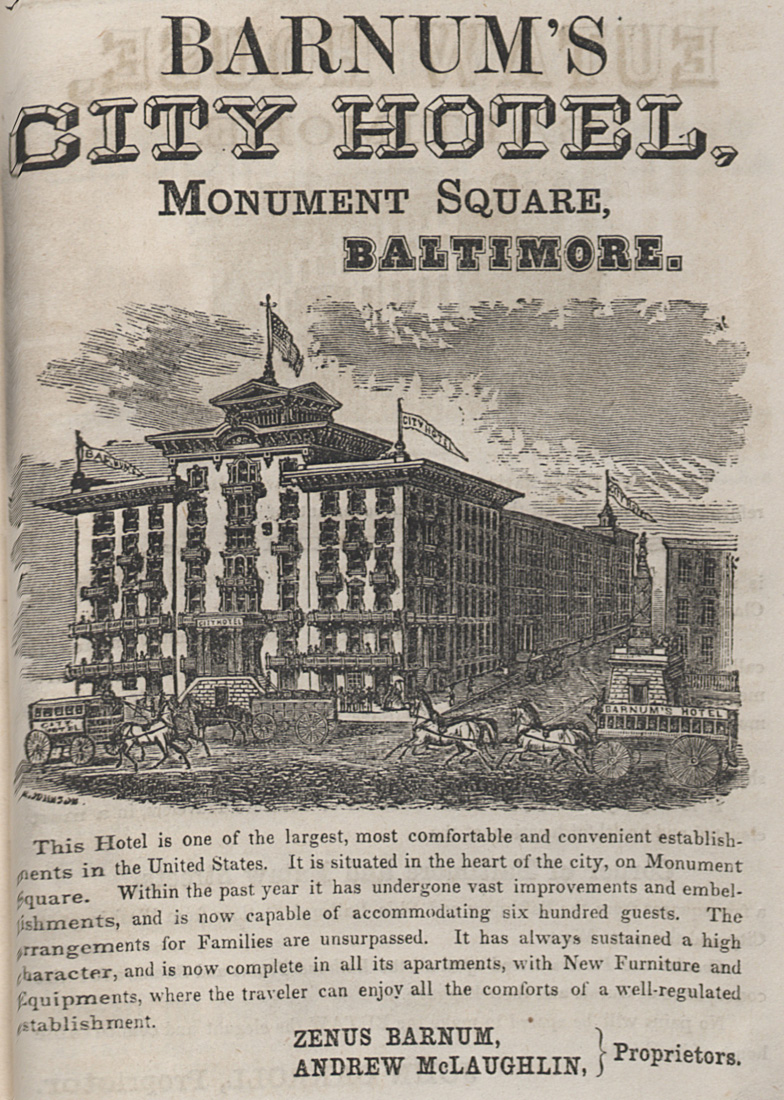

Davies was to assume the character of “an extreme anti-Union man”, also new to the city from New Orleans, and put himself up at one of the best hotels, Barnum’s.

And he was to make himself known as a man willing to pledge his loyalty and his pocketbook to the interests of the South.

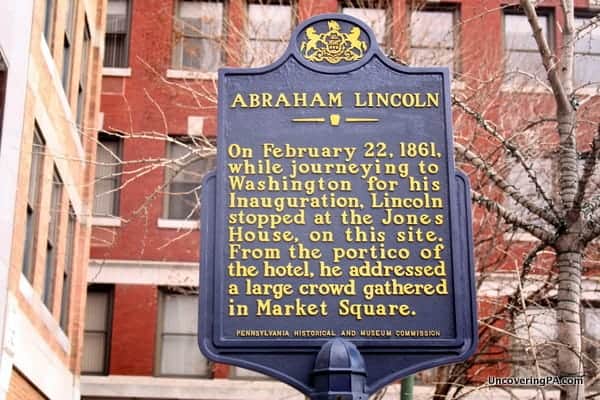

Meanwhile, from Springfield, the President-elect offered up the first details of his itinerary.

Lincoln announced that he would travel to Washington in an “open and public” fashion, with frequent stops along the way to greet the public.

His route would cover 2,000 miles.

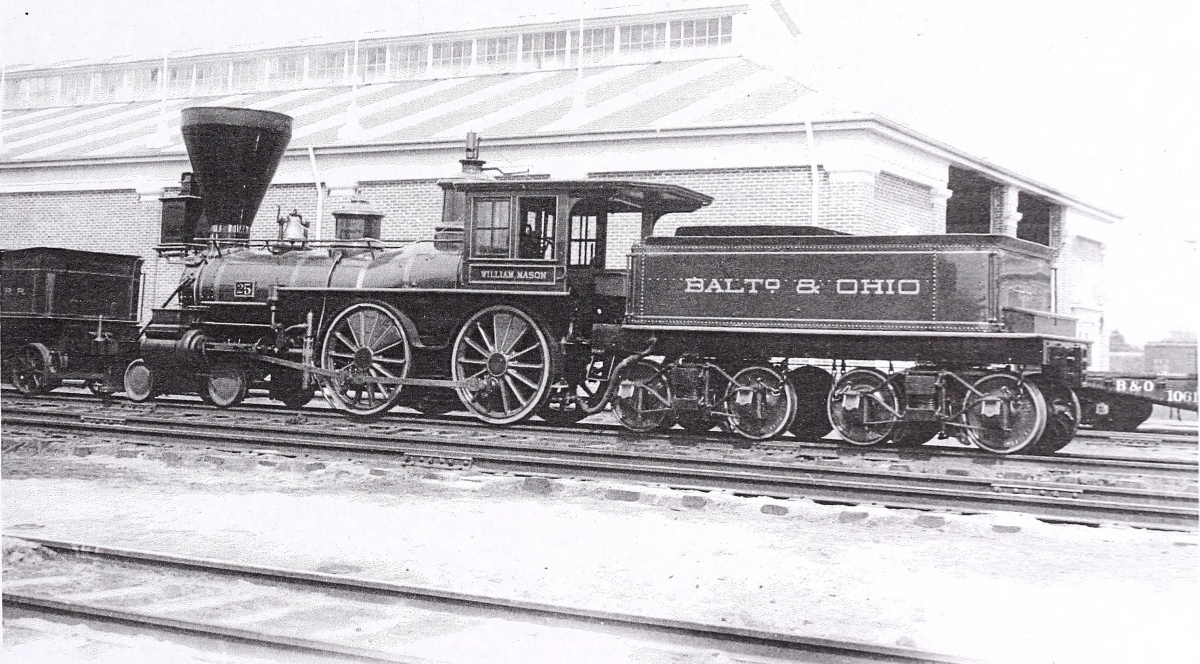

He would arrive at Baltimore’s Calvert Street Station at 12:30 on the afternoon of Saturday 23 February and depart Camden Street Station at 3.

“The distance between the two stations is a little over a mile,” Pinkerton noted with concern.

Instantly, the announcement of Lincoln’s imminent arrival became the talk of Baltimore.

Of all the stops on the President-elect’s itinerary, Baltimore was the only slaveholding city apart from Washington itself.

There was a distinct possibility that Maryland would vote to secede by the time Lincoln’s train reached its border.

“Every night as I mingled among them,” Pinkerton wrote of the circles he infiltrated, “I could hear the most outrageous sentiments enunciated.

No man’s life was safe in the hands of those men.”

A timetable for Lincoln’s journey was supplied to the press.

From the moment the train departed Springfield, anyone wishing to cause harm would be able to track his movements in unprecedented detail, even, at some points, down to the minute.

All the while, moreover, Lincoln continued to receive daily threats of death by bullet, knife, poisoned ink — and, in one instance, spider-filled dumpling.

In Baltimore, meanwhile, Davies set to work cultivating the friendship of a young man named Otis K. Hillard, a hard-drinking regular of Barnum’s.

Hillard, according to Pinkerton, “was one of the fast ‘bloods’ of the city.”

On his chest he wore a gold badge stamped with a palmetto, the symbol of South Carolina’s secession.

Hillard had recently signed on as a lieutenant in the Palmetto Guards, one of several secret military organizations springing up in Baltimore.

Pinkerton had targeted Hillard because of his association with Barnum’s.

“The visitors from all portions of the South located at this house,” Pinkerton noted, “and in the evenings the corridors and parlors would be thronged by the long-haired gentlemen who represented the aristocracy of the slaveholding interests.”

Although Davies claimed to have come to Baltimore on business, at every turn, he quietly insinuated that he was far more interested in matters of “rebeldom”.

Davies and Hillard soon became inseparable.

Just before 7:30 on the morning of Monday 11 February 1861, Abraham Lincoln began knotting a hank of rope around his travelling cases.

When the trunks were neatly bundled, he hastily scrawled an address: “A. Lincoln, White House, Washington, D.C.”

At the stroke of 8 o’clock, the train bells sounded, signaling the hour of departure from Springfield.

Lincoln turned to face the crowd from the rear platform.

“My friends”, he said, “no one, not in my situation, can appreciate my feeling of sadness at this parting. To this place, and the kindness of these people, I owe everything.

I now leave, not knowing when or whether I may return, to a task before me greater than that which rested upon Washington.”

Moments later, the Lincoln Special gathered steam and pushed east toward Indianapolis.

The next day, Tuesday 12 February, a significant break came for Pinkerton and Davies.

In Davies’ room, he and Hillard sat talking into the early hours of the morning.

“Hillard then asked me”, Davies reported later, “if I had seen a statement of Lincoln’s route to Washington City.”

Davies lifted his head, at last catching sight of a foothold among all the slippery hearsay.

Hillard outlined his knowledge of a coded system that would allow the President-elect’s train to be tracked from stop to stop, even if telegraph communications were being monitored for suspicious activity.

The codes, he continued, were only a small part of a larger design.

“My friend”, Hillard said grimly, “that is what I would like to tell you, but I dare not—I wish I could—anything almost I would be willing to do for you, but to tell you that I dare not.”