Eskişehir, Turkey, Sunday 12 June 2022

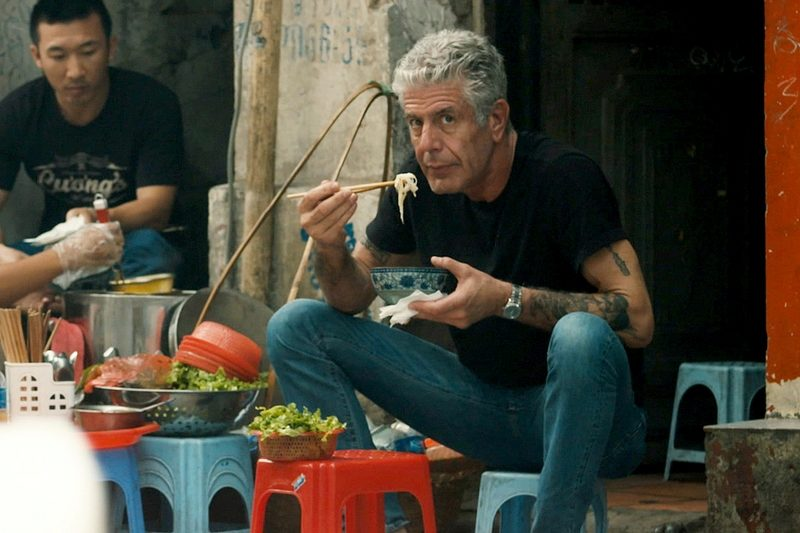

“Southeast Asia has a real grip on me.

From the very first time I went there, it was a fulfillment of my childhood fantasies of the way travel should be.”

(Anthony Bourdain)

Anthony Bourdain: Parts Unknown was an American travel and food show on CNN, which premiered on 14 April 2013.

In the show, Bourdain (1956 – 2018) travelled the world uncovering lesser-known places and exploring their cultures and cuisine.

Parts Unknown aired the last collection of episodes on CNN in the autumn of 2018.

The series finale, titled “Lower East Side” — bringing Bourdain’s culinary travelogue full circle back to Bourdain’s hometown of New York — aired 11 November 2018.

Bourdain visited (aired 19 October 2014) the former Vietnamese Imperial capital of Huê in Central Vietnam, the nation’s spiritual, cultural and culinary capital, where he tried local specialties, such as Bún bò Huê, Com hên (clams with rice topped with clam broth and pork rinds), Bánh bèo and Bánh bôt loc (cassava flour cakes topped with pan-fried shrimp, pork belly and green onions) at street vendors and restaurants.

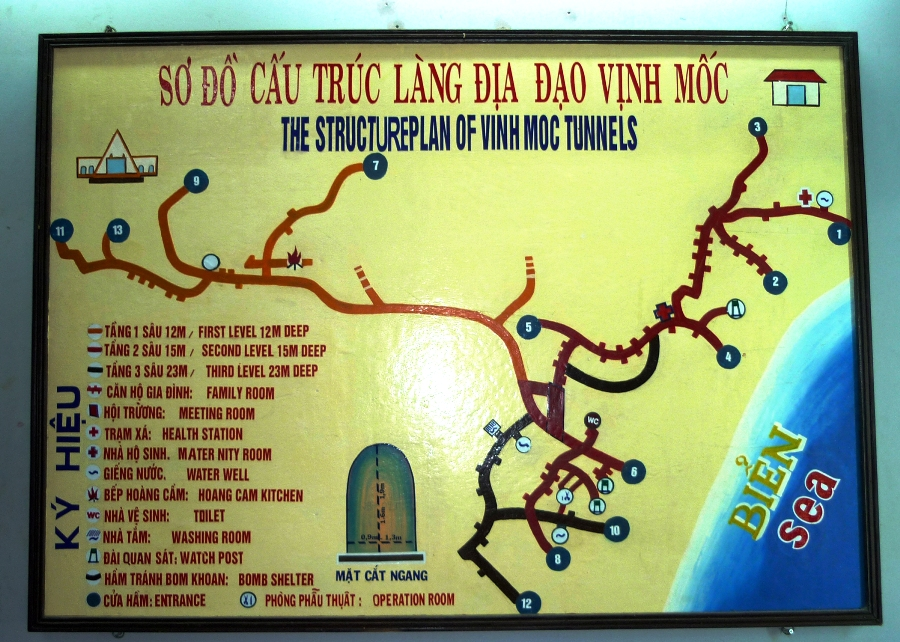

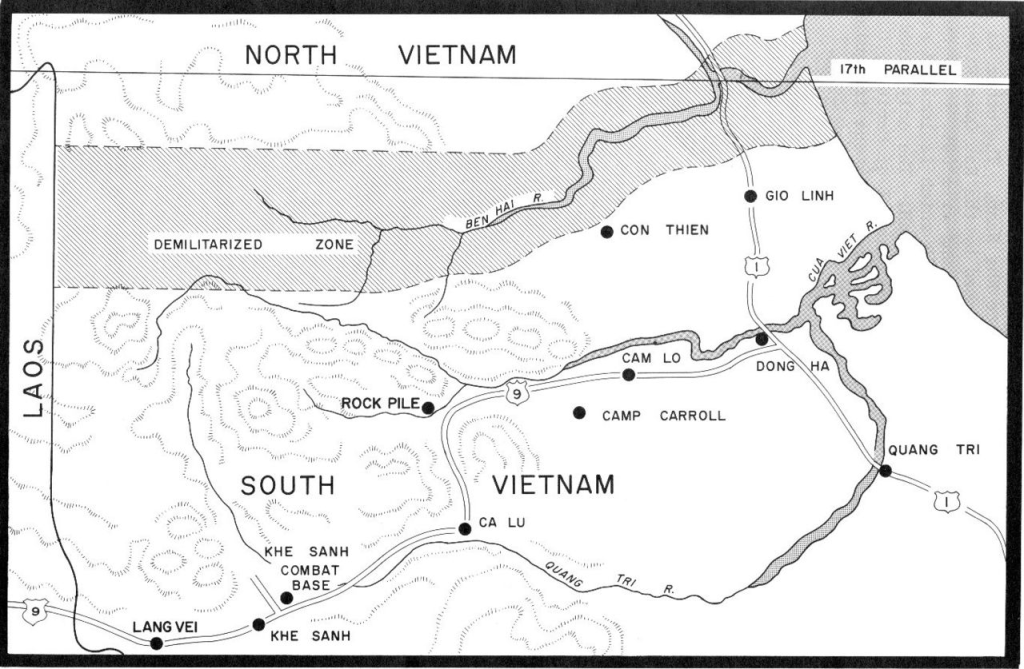

He visited Dông Ba Market, a local artist’s home sampling Vietnamese imperial court cuisine, a local fishing village, and the Communist Vinh Mõc tunnels north of the former DMZ.

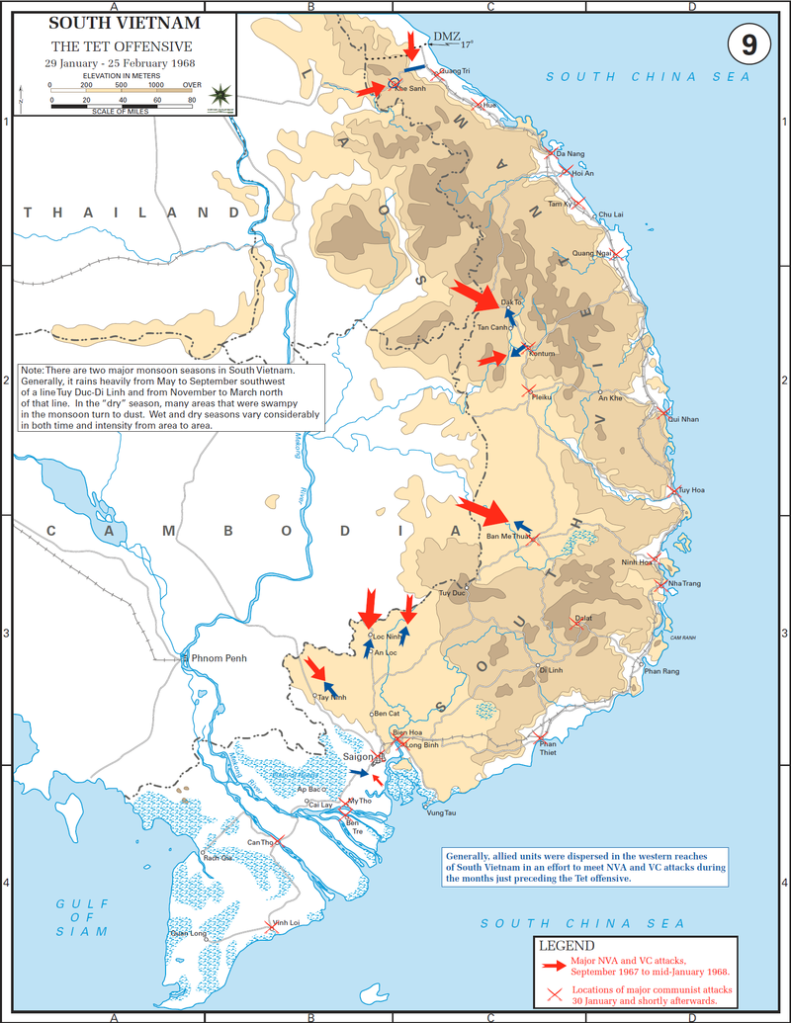

Bourdain revisited the 1968 Tet Offensive, including the Battle of Huê and the Huê Massacre, where 3,000 civilians were massacred by the Viet Cong.

For much of my life I have not been much of a TV watcher, and once I began travelling my TV watching was sporadic, at best.

I had never heard of Bourdain until I caught the news that he had died.

Bourdain was working on an episode of the show centered in Strasbourg, France, at the time of his death on 8 June 2018.

Bourdain was found dead by his friend and collaborator Éric Ripert of an apparent suicide by hanging in his room at the Le Chambard Hotel in nearby Kaysersberg.

“I’m not going anywhere.

I hope.

It has been an adventure.

We took some casualities over the years.

Things got broken.

Things got lost.

But I wouldn’t have missed it for the world.”

Anthony Bourdain

Ripert spoke of his friend and his contributions:

“He has changed the way we see the world.

He has changed the way television covers travel shows and food shows.

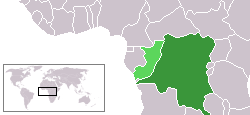

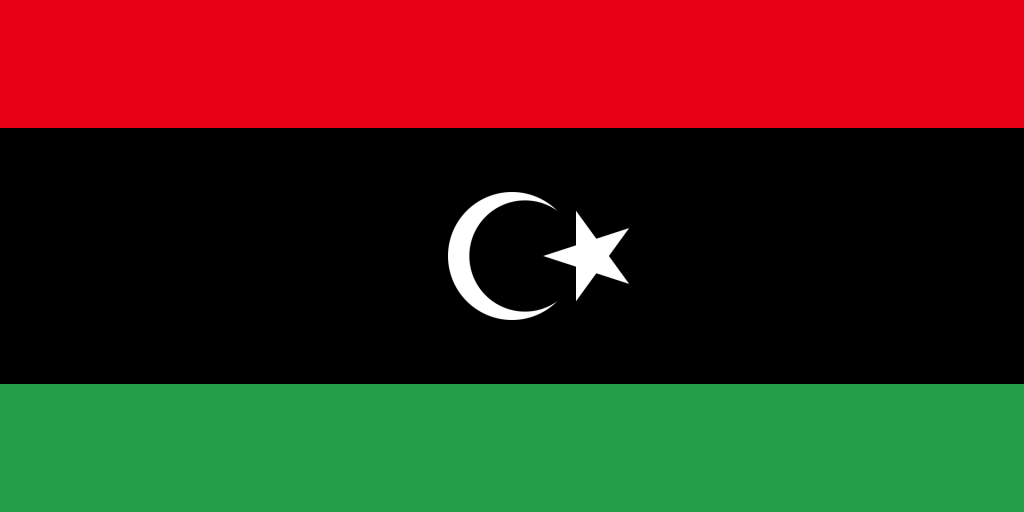

Who would have known what happened in Congo or in Libya except through his eyes?

He was giving a voice to people.

His show was not a food show.

It was not a travel show.

It was much bigger than that.

All of this, I think, it’s something that will never be forgotten.“

To this I cannot comment, but in doing research on this stage of the travels of Swiss Miss from Hanoi to Ninh Binh, I came across the vlog Mitchell Travels, paying tribute to Bourdain whilst Mitchell was visiting Tam Coc, which is en route between Hanoi and Ninh Binh.

“We are all products of our environment, nature and nurture.

When your life has been defined, when you know why you live the life you do, you understand how you got there, who helped shape you, what hurt you, how you grew to be you.”

(Mitchell Travels)

According to Mitchell, Vietnam was the country that spoke to Bourdain the loudest.

I will be honest, despite my intentions to become a vlogger one day soon, generally I dislike travel vlogs intensely, for so many of these privileged pups, in my opinion, seem to excel only in their display of arrogant cockiness and ostentatious glorification of themselves in innumerable shots of their oh-so-smug smiling faces.

And though I cannot quite bring myself to fully feel fuzzies for Mitchell, I found myself impressed with his efforts.

“1 a.m., at the Tam Coc Backpackers Hostel, one of the few places with a late night heart beat in town and as is the norm in most hostels you can find a pool table, cheap local beer and an incompetent game of amateur hour pool.

Tonight is no different.

It shouldn’t be.

This is rural Vietnam.“

(Mitchell Travels)

According to the vlog, Mitchell stayed at the Tam Coc Rice Fields Resort.

Monday 25 March 2019, Ninh Binh, Vietnam

“If I am an advocate for anything, it is to move.

As far as you can, as much as you can.

Across the ocean or across the river.

The extent to which you can walk in someone else’s shoes or at least eat their food, it is a plus for everybody.

Open your mind, get off the couch, move.”

Anthony Bourdain

Heidi and Sebastian (not their real names), she of Switzerland, he of Argentina, have been travelling together for about a week this day.

They bought motorcycles in Hanoi and set themselves a goal:

To ride down the length and coast of Vietnam to Ho Chi Minh City where she would travel on from there to Thailand and he would return back home.

They have been friends since Hanoi, where a shared ennui with a Hanoi city tour they had taken brought them together.

Heidi welcomed Sebastian for the security a male companion can bring.

He welcomed her unconditional acceptance of the special individual he is.

Maybe that is enlightenment enough, to know that there is no final resting place of the mind, no moment of smug clarity.

Perhaps wisdom is realizing how small I am and unwise, and how far I have yet to go.

Anthony Bourdain

A quiet and hazy spring morning in the Vietnamese countryside.

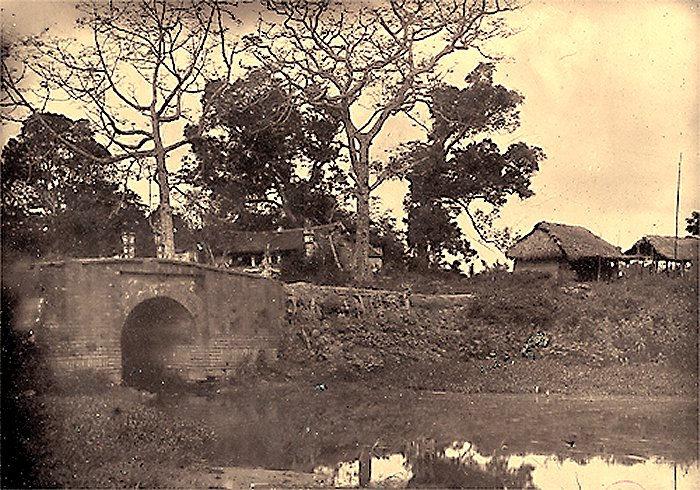

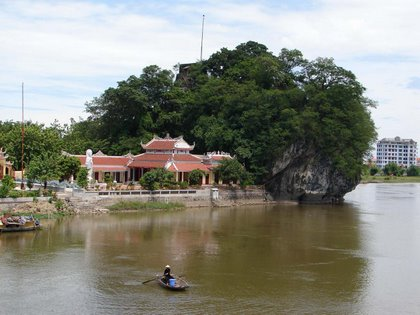

60 km south of the city of Hanoi, on the river Dáy, Phủ Lý is the capital city of Hà Nam Province.

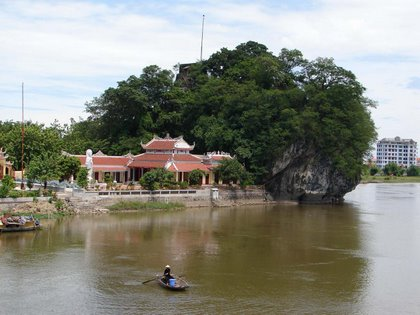

Located at Nguyen Van Troi Street, Bau Pagoda is a scenic spiritual place, a long-standing sacred place in a vast land.

In front of the pagoda is a deep and wide lake, connected with the Dáy River, beautiful scenery that adds to the tranquility of the pagoda.

According to the theory of yin and yang there are five elements.

In front of a temple, there is usually a lake, because according to legend, temples represent yang, lakes represent yin.

Yang and yin create a harmonious balance in Heaven and Earth.

According to feng shui theory, temples are places of sanctity and respect.

The lake in front of the temple seems to remind people who come to this place to wash their hands and feet to remove all the dust in order to sincerely worship.

Thus, the spiritual is never distant from the physical.

The Bau Pagoda combines the traditional spirit of the nation with the new ambitions of today.

It is a combination of national and modern dharma.

According to old documents, Bau Pagoda is over a thousand years old.

This has been a place of spiritual and cultural activities for many generations.

Bau Pagoda still preserves many precious artifacts from the past.

Along with churches and temples in the city, Bau Pagoda is a temple that create a feeling of peace and quiet in the noisy city.

Travel changes you.

As you move through this life and this world you change things slightly, you leave marks behind, however small.

And, in return, life and travel leaves marks on you.

Most of the time those marks on your body or on your heart are beautiful.

Often though they hurt.

Anthony Bourdain

Ha Nam Province, in the words of the late professor Tran Quoc Vuong, is a locality located in the “water quadrilateral” of the Red River Delta – one of the biggest cradles of the art of rowing in Vietnam.

Ha Nam was the pioneer province in making a dossier to submit to UNESCO to recognize the art of Cheo singing as a representative Intangible Cultural Heritage of humanity.

Ha Nam Cheo Theatre, located at Ly Thai To Street, keeps Cheo art alive.

Continue south to Van Long.

The Van Long Wetland Nature Reserve is a nature reserve in Gia Vien District, along the northeastern border of Ninh Binh Province.

The site is one of the few intact lowland inland wetlands remaining in the Hong River Delta.

Limestone karst is surrounded by the freshwater lake, marshes and swamps.

Together with subterranean hydrological systems they form a wetland complex, which is very rare in mainland Southeast Asia.

The Van Long Wetland Nature Reserve is a habitat for the critically endangered Delacour’s langur and may be the only place in the world where the species can be observed in the wild.

Since 1960, a dike line of more than 30 km long was built on the left bank of the Dáy River, turning Van Long into a wetland 3,500 hectares wide, attracting many birds to stop and feed mid-migration.

Isolated mountains, rocky islands in the middle of a vast valley, have “accidentally” become the salvation for many species of animals and plants to escape human destruction.

But the most valuable coincidence was when foreign experts discovered that Van Long has more than 40 individuals of the white-breeded langur.

This discovery surprised the scientific community, because the langur is a highly endangered species.

The study of Van Long lagoon area has brought scientists from one surprise to another, because the flora and fauna here are very typical for both the two ecosystems of limestone mountains and wetlands of the Red River Delta.

In addition to the langur, there are many species of animals and plants, such as broadleaf conifers, money-flowers, flower slices, horse bears, leopards, salamanders…

Here also is an insect species that is close to extinction, a species of ca cuong belonging to the swimming leg family.

The only place where this particular species of ca cuong can live must have a really clean water environment.

In the flooded areas of Van Long, there are ca cuong species (Belostomatidae), a group of rare insects, the living expression of the purity of the water environment here, which help people to destroy molluscs carrying parasitic diseases.

Currently, Van Long is supported by the Dutch government, the Global Environment Facility (GEF) and the Cuc Phuong Rare Primate Rescue Center, which strives to conserve rare mammal species.

Van Long wetland is an area with diverse ecosystems.

In addition to the two main ecosystems of wetlands and forests on limestone mountains, there are also ecosystems of fields, lawns, shifting cultivation and village ecosystems.

The flora ecosystem in Van Long has 722 species.

Particularly noteworthy are absinthe, broad-leaved conifers, tonic cones, fern sage, cycads, and canola flowers.

The fauna ecosystem of Van Long area is very rich.

Here, there are rare animals, such as langurs, bears, chamois, red-faced monkeys, leopards, reptile frogs, king cobras, flower lizards, ground pythons, buffalo snakes, red-haired striped snakes…..

Delacour’s langur males weigh between 7.5 and 10.5 kg (17 and 23 lb), while the females are slightly smaller, weighing between 6.2 and 9.2 kg (14 and 20 lb).

Their fur is predominantly black, with white markings on the face and distinctive creamy-white fur over the rump and the outer thighs, while females also have a patch of pale fur in the pubic area.

The Delacour’s langur has a crest of long, upright, hair over the forehead and crown.

Delacour’s langurs are diurnal, often spending the day sleeping in limestone caves, although they sleep on bare rocky surfaces if no caves are available.

They are folivorous, with about 78% of the diet reportedly consisting of foliage, although they also eat fruit, seeds, and flowers.

The monkeys have been reported to eat leaves from a wide range of different plant species, indicating that their apparent dependence on limestone habitats is not related to their diet.

In previous decades, Delacour’s langurs were reported to live in troops of up to 30 individuals, often including a mix of males and females, although single-male groups are more common, and some small all-male groups have also been reported.

In more recent years, the typical group size seems to be much smaller, with only about four to 16 members each.

Males defend the troop’s territory from outsiders, often standing watch on rocky outcrops.

When potential rivals are spotted, the males in a troop initially try to intimidate them with loud hoots and visual displays, resorting to chasing and fighting if this fails.

Within the group, social bonds are maintained by grooming and play.

Despite living in forested habitats, Delacour’s langurs are primarily terrestrial, only occasionally venturing into the trees.

They swing by their hands when travelling through trees, and use their tails for balance when rapidly scrambling over steep rocky terrain.

Females give birth to a single young after a gestation period of 170 to 200 days.

The young are born with orange fur, and are precocial, with open eyes and strong arms.

The fur begins to turn black at around four months, and the young are probably weaned at 19 to 21 months, when the mother is likely ready to breed again.

However, the full adult coat pattern is not achieved for around three years.

Females reach sexual maturity at four years, and males at five years.

The total life expectancy is around 20 years.

Above: Delacour’s langur monkeys – mother and child

Classified as critically endangered by the International Union of the Conservation of Nature (IUCN), the primary threats to the species are their being hunted for traditional medicine, loss of forest habitat and the local development of tourism.

As of 2010, less than 250 of these animals were believed to remain in the wild, with nineteen in captivity.

Van Long also has the ability to form a bird garden with tens of thousands of storks often feeding in marshy fields and rice fields.

And, truth be told, as the wetlands in Van Long have not been fully studied, it is also likely to be an important site for migratory waterbirds, such as the ginseng bird (Fulicra atra).

One notable resident in Van Long is the Bonelli’s eagle (Hieraaetus fasciatus).

To date, Van Long is the only place that has accurately recorded this eagle species in Vietnam.

Not only a nature reserve, Van Long is also a place with attractive landscapes.

Van Long is known as “the bay without waves“, because when travelling on a boat on the lagoon, visitors will see the water surface as flat as a giant mirror, as still as an ink landscape painting.

Van Long area has a thousand beautiful caves.

Particularly, Ca Cave is very beautiful and is the gathering and breeding place of catfish, perch, and banana fish.

Shadow Cave is another beautiful cave worth seeing.

Adjacent to Van Long conservation area, there is also the Van Long tourist service area, an impressive architectural complex.

This is the resting place of tourists in their mid-migrations.

Van Long Lagoon is a unique eco-tourism destination, attracting tourists from France, Korea and Japan.

In the vicinity of Van Long area, there are many famous historical and cultural attractions, such as:

- Dinh Bo Linh Temple

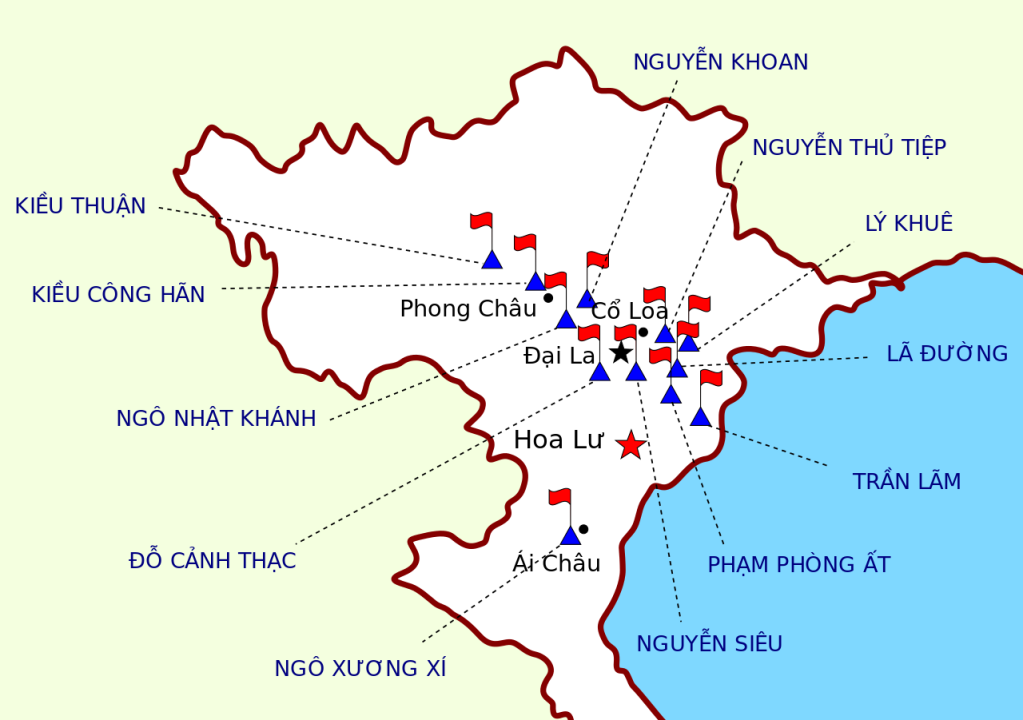

Đinh Bộ Lĩnh (924–979) (r. 968–979) was the first Vietnamese emperor following the liberation of the country from the rule of the Chinese Southern Han Dynasty, as well as the founder of the short-lived Dinh Dynasty and a significant figure in the establishment of Vietnamese independence and political unity in the 10th century.

He unified Vietnam by defeating 12 rebellious warlords and became the first emperor of Vietnam.

Upon his ascension, he renamed the country Đại Cồ Việt.

Đinh Bộ Lĩnh was born in 924 in Hoa Lu (south of the Red River Delta in what is today Ninh Binh Province).

Growing up in a local village during the disintegration of the Chinese Tang Dynasty that had dominated Vietnam for centuries, Đinh Bộ Lĩnh became a local military leader at a very young age.

From this turbulent era, the first independent Vietnamese polity emerged when the warlord Ngô Quyèn defeated the Southern Han’s forces in the First Battle of the Bach Dang River in 938.

However, the Ngô Dynasty was weak and unable to effectively unify Vietnam.

Faced with the domestic anarchy produced by the competition of 12 feudal warlords for control of the country, as well as the external threat represented by Southern Han, which regarded itself as the heir to the ancient kingdom of Nan Yue that had encompassed not only southern China but also the Bac Bo region of northern Vietnam, Đinh Bộ Lĩnh sought a strategy to politically unify the Vietnamese.

Upon the death of the last Ngô king in 965, he seized power and founded a new kingdom the capital of which was in his home district of Hoa Lu.

To establish his legitimacy in relation to the previous dynasty, he married a woman of the Ngô family.

In the first years of his reign, Đinh Bộ Lĩnh was especially careful to avoid antagonizing Southern Han.

In 968, however, he took the provocative step of adopting the title of Emperor (Hoàng Đế) and thereby declaring his independence from Chinese overlordship.

He founded the Đinh Dynasty and called his kingdom Dai Cô Viêt.

His outlook changed, however, when the powerful Song Dynasty annexed Southern Han in 971.

In 972, Đinh Bộ Lĩnh ingratiated himself with the Song by sending a tribute mission to demonstrate his fealty to the Chinese Emperor.

Emperor Taizu of Song subsequently recognized the Viet ruler as Giao Chi Quận Vương (King of Giao Chi), a title which expressed a theoretical relationship of vassalage in submission to the Empire.

Well aware of Song’s military might, and eager to safeguard the independence of his country, Đinh Bộ Lĩnh obtained a non-aggression agreement in exchange for tributes payable to the Chinese court every three years.

- Hoa Lu Cave

Hoa Lu Cave was the first base of the military envoy Dinh Bo Linh for the unification of Vietnam in the 10th century.

The cave is located about 15 km north of the ancient capital of Hoa Lu and 20 km from Ninh Binh City by road.

The cave is in an exposed valley of about 16 acres surrounded by arc mountains.

The four sides of Hoa Lu Cave are surrounded by extremely solid rocks, with only one entrance, a small cave about 30 m high.

Outside the cave is Cut Lagoon, about 3 km long and 500m wide, like a natural moat.

From here you can row, row, row your boat to Day River.

- Dich Long Pagoda Cave

Dich Long Cave and Pagoda is a famous tourist destination of Ninh Binh Province.

It is a temple built 80 metres up a karst tower also named Dich Long.

Dich Long Cave and Pagoda is located in Gia Thanh Hamlet, Gia Vien District, Ninh Binh Province, near National Highway 1A.

According to one legend the cave was found out in 1739 by a woodcutter.

He created an altar after seeing stalactites that look like Buddha inside the cave.

In 1740, the Pagoda was established.

Tourist coming to Dich Long will be surprised by a large number of unique architecture: a temple for worship, a crescent lake, five three-storey towers and three lower temples.

Especially noteworthy are three statues of Buddha, which have historical value.

The bell tower is in the main gate with the rocky columns.

Engraved stone is the characteristic feature.

The stone temple behind the bell tower, for worshiping Saint Nguyen Minh Khong, contains five compartments.

The eight monolithic stone columns are huge at 4 metres high.

The giant dragons were carved on these columns winding through the clouds.

The engraving is so sophisticated that people may imagine that the dragons seem to be flying up.

The other eight column are 3 metres high and engraved with Chinese characters which concisely but profoundly glorify the beauty of this place.

The tourists will not find other temples made of precisely engraved bluestone on their Ninh Binh Province tour.

This temple is unique.

On the left side of the stone temple is the Buddha Garden.

All the stone Buddha statues in this Garden were made by master craftsmen.

The Garden creates the sacred atmosphere of Dich Long Pagoda.

Behind the stone temple is the three-compartment lower pagoda.

The pagoda is on the halfway mark to the top of the mountain.

This pagoda is related to many historical events.

The Temple still bears the traces of war.

During the anti-French resistance, Dich Long Pagoda was the shelter of the people and the victim of bombing raids.

From the main pagoda, continue to climb 105 stone steps to the cave divided into three areas: the Buddha Cave, the Dark Cave and the Light Cve.

Many stalactites look like sacred animals changing with the light into forms such as dragons, elephants, etc.

This always strongly impresses visitors coming here.

There are three caves beneath the temple, to the right is a chamber with stalactites, stalagmites, and Buddha statues which is used for prayers.

To the left is a cave called Toi or Dark Grotto.

It is famous for a huge stalagmite resembling a woman’s breast.

Behind this cave is the Sang or Light Grotto which has a wide opening so the light and the wind can enter the cave.

When a breeze plays on the conical stalagmites, they sound like flutes.

This explains the name Dich Long, which translates literally Flute Wind.

Every year there is a great festival at the Temple, on the 6th and 7th of March.

There are religious elements like worshipping Buddha and thurification (the act of burning incense) and there is entertainment, like performing kylin dances, dragon dances, a chess tournament, a competition in writing Han scripts, and more.

Near Van Long Wetland Nature Reserve, the Emeralda Ninh Binh Resort includes 51 villas with 170 4-star bedrooms, 116 standard rooms, 36 deluxe rooms and 10 duplex suites, as well as restaurants, bars, spa and fitness centres, two swimming pools, tennis courts, event areas, conference rooms and babysitting areas.

Where Delacour’s langurs rest is never discussed.

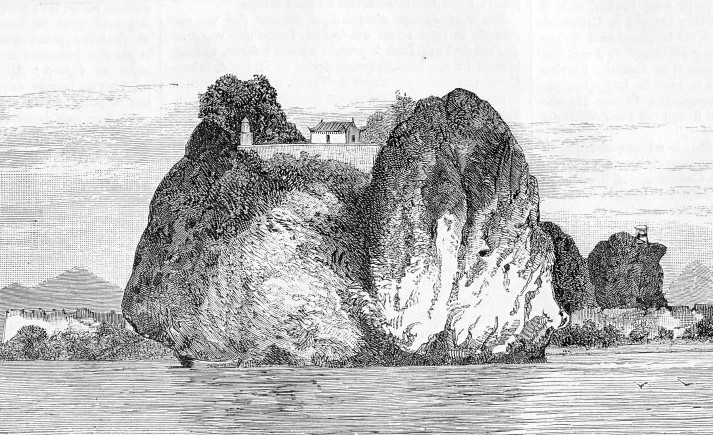

It is hard not to be won over by the mystical watery beauty of the Tam Coc “Three Caves” region, which is effectively a miniature landlocked version of Ha Long Bay.

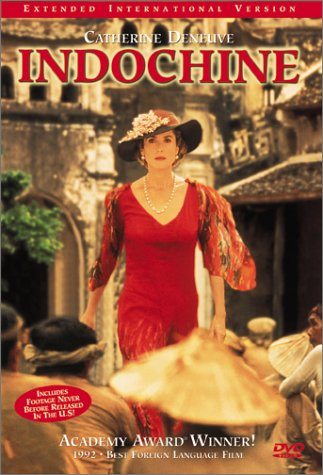

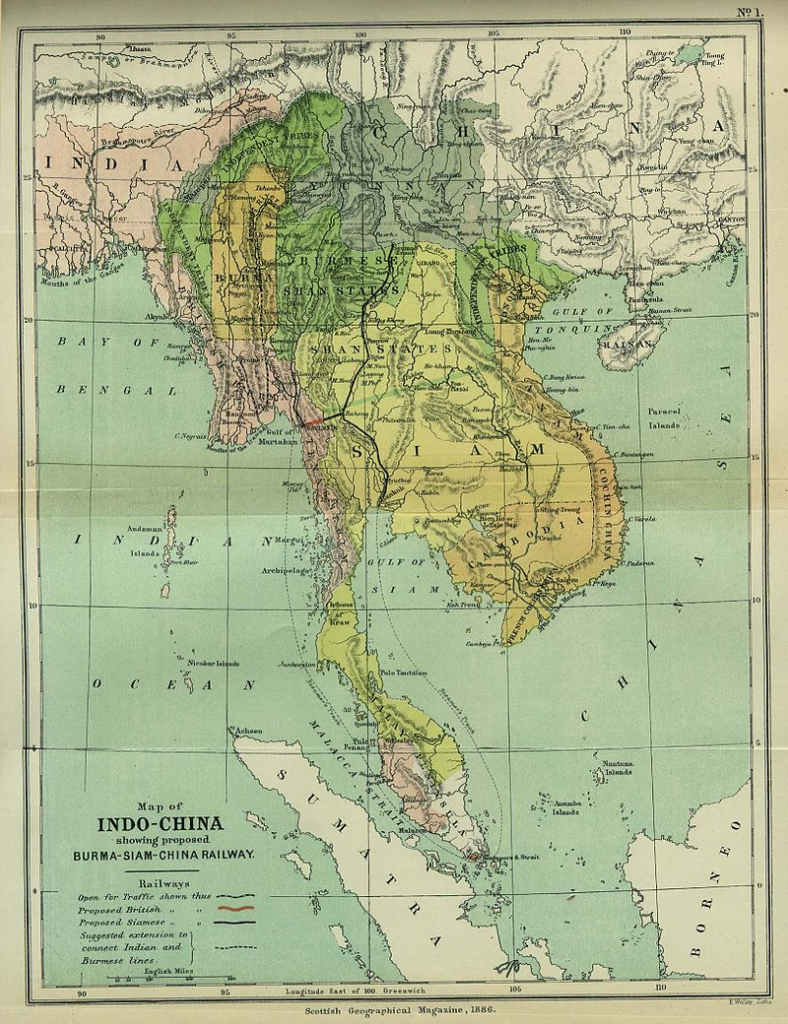

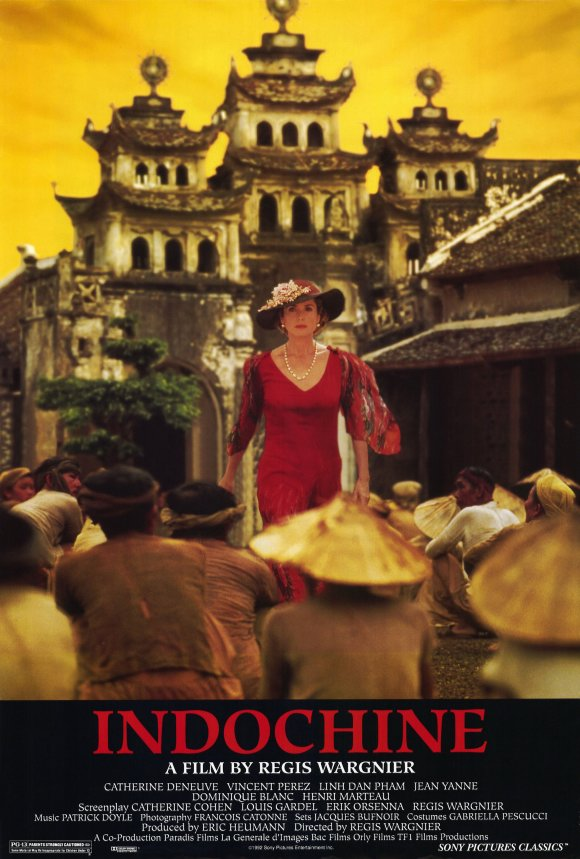

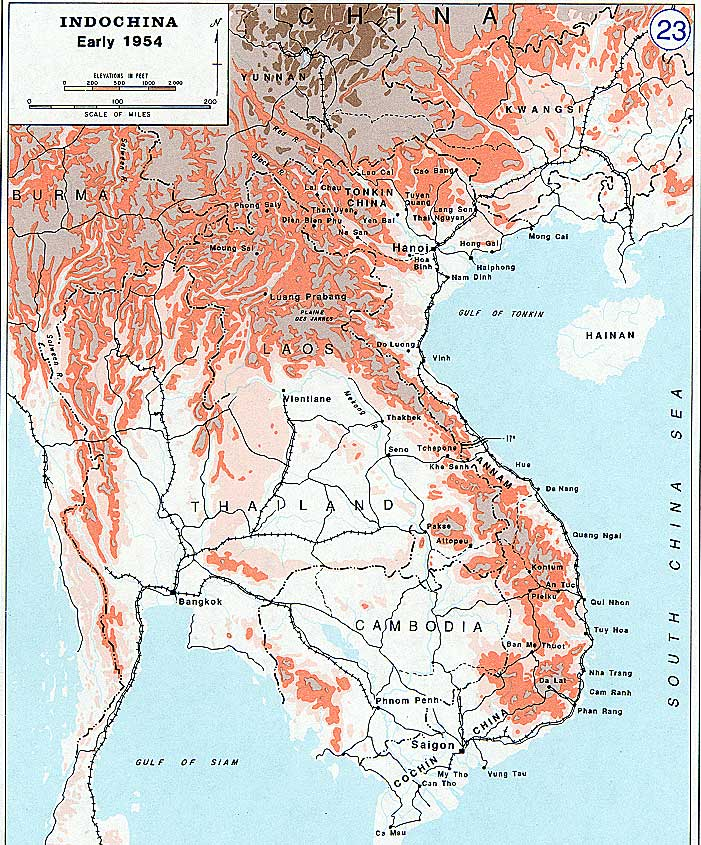

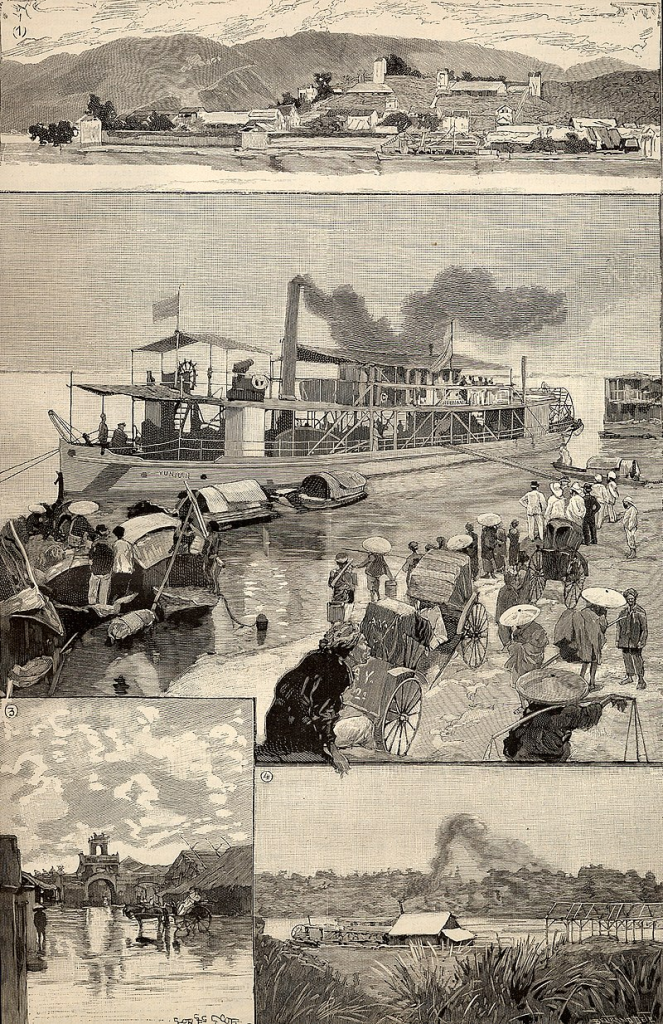

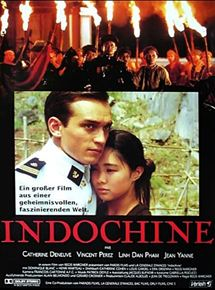

The film Indochine helped to put it on the tourist map, and both good and bad have come of its burgeoning popularity – access roads have been improved, though some of the canal banks themselves have been lined with concrete.

In addition, Tam Coc has become relentlessly commercial, with many travellers having a wonderful day spoiled by hard-sell antics at the end of their trip.

Despite the overzealous – occasionally aggressive – peddling of embroideries and soft drinks by the rowers, the two-hour sampan-ride is a definite highlight, especially as the men and women row with their feet and make it look easy.

Boat rides on traditional sampans are the highlight in Tam Coc, meandering through dumpling-shaped karst hills in a flooded landscape where the river and rice paddies merge serenely into one.

Keep an eye open for mountain goats high on the cliffs and bright darting kingfishers in the waters.

Journey’s end is Tam Coc, three long, dark tunnel-caves (Hang Ca, Hang Giua and Hang Cuoi) eroded through the limestone hills with barely sufficient clearance for the sampan after heavy rains.

The Tam Coc – Bich Dong tourist region currently has a natural area of 350.3 hectares and is located 2 km from National Highway 1, 7 km from Ninh Binh City, 9 km from Tam Diep City.

Pick-up centers are distributed at the following points:

- Tam Coc

- Co Vien Lau

- Nang valley

- Nham valley

- Bich Dong Pagoda

- Mua Cave

The Tam Coc – Bich Dong tourist region includes:

- Cruises: Van Lam wharf – Ngo Dong River – Tam Coc / Bich Dong / Sunshine Valley

- Tourist attractions: Bich Dong Mountain and Pagoda / Tien Cave / Mua Cave / the ancient house of Co Vien Lau / Thai Vi Temple / Thien Huong cave

Tam Coc, which means “three caves“, includes Ca Cave, Hai Cave and Ba Cave.

All three caves were formed by the Ngo Dong River crashing through the mountain.

- Ca Cave is a 127 metre long incursion through a large mountain. The mouth of the cave is over 20 metres wide. Bring a sweater as the cave can be quite chilly. Many stalactites of various shapes hang down.

- Hang Hai, nearly 1 km from Ca Cave, is 60 metres long. The ceiling of the cave has many strange hanging stalactites.

- Hang Ba, near Hang Hai, is 50 metres long. The ceiling of this cave is like a stone arch and lower than the other two caves.

Wanting to visit Tam Coc, visitors can get off the boat from the central wharf.

Boats take tourists on the Ngo Dong River that winds past cliffs, water caves, and rice fields.

The travel time is about 2 hours.

The scenery of Tam Coc, especially the shores of the Ngo Dong River, can change according to the rice season (green rice, golden rice or the silver colour of the water in the fields).

The beauty of Tam Coc comes from the intricate maze of mountains, river valleys and wetlands that have let it be nicknamed “the inland Ha Long Bay“.

Above: Ha Long Bay

The main river boat tour is a must – a roughly two-mile thoroughfare through Vietnam’s live action version of Avatar’s planet Pandora.

As your rickety tin sampan boat further rows up the sleepy Ga Dong River, the landscape becomes ever more mysterious, it is then that you comprehend the irony that the natural complexity of your surroundings is what makes you appreciate the simplicity of its feel.

Like Huckleberry Finn drifting down the muddy Mississippi River, the traveller is without a care, alone with only thoughts as companions.

On the way back, you can ask to stop at Thai Vi Temple, a short walk from the river.

Dating from the 13th century and dedicated to the founder of the Tran Dynasty, it’s a peaceful, atmospheric spot.

Thai Vi Temple is the place to pay homage to kings, generals, and a queen.

The Tam Coc mountain area was the place where the Tran dynasty came to set up Vu Lam Palace in the resistance war against the Nguyen Mong.

Thai Vi Temple can be reached by foot from Tam Coc or by road 2 km from Tam Coc boat station.

King Tran Thai Tong (r. 1255 – 1258) started the construction of Vu Lam Palace on an elevation near Ca Cave.

During the construction of the amphitheatre, Thai Vi recruited exiles to reclaim and establish hamlets, expand roads, embellish key places, and prepare against invasion.

Many important court meetings were held here.

During the second resistance war against the Nguyen Mong Empire in 1285, the Vu Lam Hanh Palace area became a solid base of the Tran army and people.

On 7 May 1285, the year of the Rooster, the two kings Tran Thanh Tong and Tran Nhan Tong defeated a part of the Mongol-Yuan army here, “beheading and cutting off the enemy’s ears unspeakably“.

The battle took place in the Thien Duong limestone valley.

In the middle of the valley, there is Cua Ma Field and the nearby Valley of Tombs, so named because there are many graves here and locals still call this valley a “war ground“.

The battle quickly swept the Mongols out from Dai Viet, once again showing that Truong Yen was not only the imperial capital but also the land of the Vietnamese Emperor.

In addition to its strategic position, the Vu Lam palace area is also a place filled with majestic beautiful nature.

Tran Thai Tong compared this place to a fairy land:

The eternal water consciousness of Bong Lai,

Valley of the moon and moon of the mortal world.

The book “Khâm Định Đại Việt su tong muong muc” speaks more clearly:

“Here the mountains overlap.

There are caves in the mountain guts.

The mountain circumference is as wide as the mountains.

Outside there is a small river winding and winding, connecting to the mountains.

Small boats can be carried in.“

There is a description of Vu Lam’s palace, in the poem Vu Lam Thu Van (Autumn afternoon in Vu Lam).

Tran Nhan Tong wrote:

The slot is printed upside down for the suspension ball

Sneeze at the edge of the crevice of the sun

Quietly a thousand young, falling red leaves

Clouds spread like a distant bell

After the first resistance war against the Mongol invaders (1258), 40-year-old King Tran Thai Tong ceded the throne to his son and returned to the Truong Yen mountains to establish the Vu Lam palace base.

King Tran Thanh Tong also built a number of other palaces here and made a road from Van Lam village to the Palace, and had built a stone dragon bridge across the Ngo Dong River over Dragon Culvert.

Vu Lam Palace was the first Buddhist monk monastic home of Emperor Tran Nhan Tong.

Dai Viet historical recorder Toan Thu wrote in the 7th month of the year of the Horse (1294):

“The emperor came to Vu Lam to visit the rock cave.

The stone mountain gate is narrow.

The emperor sat in a small boat with the queen empress Tuyen Tu at the stern.”

In the year of the Cat (1295), the Dai Viet historical record reads:

“In the summer, in June, the emperor returned to the scriptures.

Having left home, to Vu Lam palace he returned again.”

Vu Lam served as a palace for at least 41 years (1258 – 1299).

In front of the temple, there is a jade well built of green stone.

Behind the temple is the Cam Son rock mountain range.

Outside of Nghi Mon, there are two horses made of monolithic green stone on both sides.

Through Nghi Mon, there is a steeple made of ironwood, while the roof is tiled.

Here hangs a bell cast from the 19th year of Chinh Hoa.

Opposite the steeple along the main road is a stele tower and three steles erected on either side.

The four-sided stele records the merits of those who have contributed to the construction of the temple.

The main road and the dragon yard are paved with green stone.

The dragon yard is about 40 square metres wide.

On both sides of the dragon yard are two rows of Vong houses – where the ancestors discussed the sacrifices in the past.

From the dragon yard, follow the stone steps ascending to a height of 1.2m to reach the Five Great Gate (five large doors) with six parallel rows of round stone columns all carved with the dragon king embossed in front.

The outside of the stone columns are carved with parallel sentences of Chinese characters.

The verandas are also made of stone, carved with two dragons adoring the moon.

Through the five large doors, there are five majestic Bai Duong pavilions.

There are also six square stone columns carved with parallel sentences on the outside, embossed on the other sides with all manner of beasts.

Next are three Trung Duong pavilions with two rows of round stone columns, each row with four columns, all carved with dragon clouds.

Here is put into the stone – incense.

The two sides have a pair of wooden cranes more than two metres high with two sets of gold medallions.

Through Trung Duong in the Chinh Tam Pavilion, there are also eight round stone columns carved with relief.

Thai Vi Am remains to this day is an area of about six acres wide, surrounded by earthen ramparts, in the middle of which is a temple.

In the middle of the Palace are statues of kings (Tran Thai Tong, Tran Thanh Tong, Tran Nhan Tong, Tran Anh Tong), of generals (Tran Hung Dao, Tran Quang Khai) and of a queen (Thuan Thien).

On the left and right are two bronze statues of females standing in service of the King.

At the Thai Vi temple ruins, there is a small temple where King Tran Thai Tong stayed to practice his faith in the last years of his life.

Thai Vi Temple Festival is held from the 14th to the 17th day of the 3rd lunar month to commemorate the merits of the first kings of the Tran Dynasty.

The procession is led by a drum carried by two people, one who wears a robe and a swallow’s hat, followed by five people holding flags.

Then there is a palanquin with bowls of tribute on it, with images of the kings, queens, or princesses of the Tran dynasty, accompanied by the scent of incense and flowers.

The palanquin has a very beautiful, swinging red umbrella.

Next is a palanquin of four people carrying offerings of flowers and fruits.

The palanquin procession at Thai Vi Temple is not one group, but more than 30 groups.

On the morning of 14 March, a palanquin from the roads in the district and province is carried to Thai Vi temple in the jubilant atmosphere of the festival.

The palanquins are all gorgeously painted with gilded lipstick as young people dress up according to the old festival customs.

Sacrifice is an important ritual, held in front of the temple.

The priesthood consisting of 15 to 20 people carry out the incense and drink.

The chief priest reads literature and recites the song of praise and merit of King Tran Thai Tong.

After each sacrifice, a man plays the lute and a woman explains the ca tru way.

As part of the festival, there are games, such as the lion dance, the dragon dance, human chess, wrestling, boating, and, oh, the fun you will have!

Located deep in the mountainous area of Trang An, visitors sit in traditional boats steered by local people, and experience a close connection with nature, feel the pure and splendid beauty of caves and strange rocks, and learn of the golden features of the nation’s history in the process of building and defending the country.

From Trang An wharf, about 15 minutes by boat through Lam Cave, you can enter Noi Lam Valley.

Here, the Vietnam Institute of Archeology excavated and explored the valley and found thousands of artifacts on the surface and in the dug holes.

Dr. Le Thi Lien of the Vietnam Institute of Archeology said:

After a period of excavation and archaeological survey of Noi Lam valley – a place belonging to Vu Lam palace of Tran dynasty, archaeologists have discovered many remarkable vestiges, such as:

- traces of clay-containing areas for ceramic materials

- traces of trees in the black mud

- traces of stone embankment road or water wharf

- traces of the embankment

This result shows the possibility of pottery production in this area.

In addition, there are relics obtained with 5,525 fragments lying on the surface and 940 pieces of relics of all kinds appearing in the dug holes.

Through research, analysis has discovered many relics of great value: architectural decorative pieces, glazed ceramics, earthenware, lumps of rice, coal-fired rice.

Archaeologists hypothesize that this area was the production site of glazed ceramics in the Tran Dynasty.

The discovery of traces of clay material reserve and remnants of waste shows the possibility of pottery production here.

Located in the middle of Noi Lam valley, by Tien Stream, there are temples paying homage to the kings and mandarins of the Tran dynasty.

Truong Han Sieu was a famous artist and guest.

He had a strong character, a profound education, and made great contributions to the 2nd and 3rd resistance wars against the Yuan Mongols.

During the period when King Tran Nhan Tong returned to this land to practice his faith, Truong Han Sieu also retired to this hermitage and set up a monastery to practice in his hometown of Ninh Binh.

This is why Truong Han Sieu is also honoured at this relic by the people.

Be mindful when choosing your boat to stay clear of those with boxes, as these usually mean that your rower will haggle you endlessly until you have purchased something from them – it can ruin your relaxing ride if you do not wish to buy something.

Also, be aware that hawkers will sometimes convince you to buy a drink for your guide/rower, however, your oarsmen or women will quickly sell this back to them for half the price once you have left.

The landscape here is flat, so bike riding through the rice fields is recommended and makes you feel like you are in a movie scene.

Ride at ease whilst taking in the breathtaking views and lush green colours.

Ride through bamboo-lined village roads to learn about the culture and customs of farmers in wet rice areas.

Imagine being a shepherd, herding buffalo, slapping fish, catching crabs, grinding rice and pounding rice, enjoying rustic dishes, such as grilled perch, crab soup with salted eggplant….

Thien Duong Cave, located on the road from Ngo Dong River to Thai Vi Temple, is a dry and bright cave located halfway up the mountain at an altitude of about 15 metres.

The cave is about 60 m high, 40 m deep, and 20 m wide.

The top of the cave is hollow, so the cave is also called Troi Cave.

Nestled in the cave is a shrine dedicated to Tran Thi Dung, the wife of King Ly Hue Tong, and said to be the person who taught the people of Ninh Hai Commune the craft of embroidery.

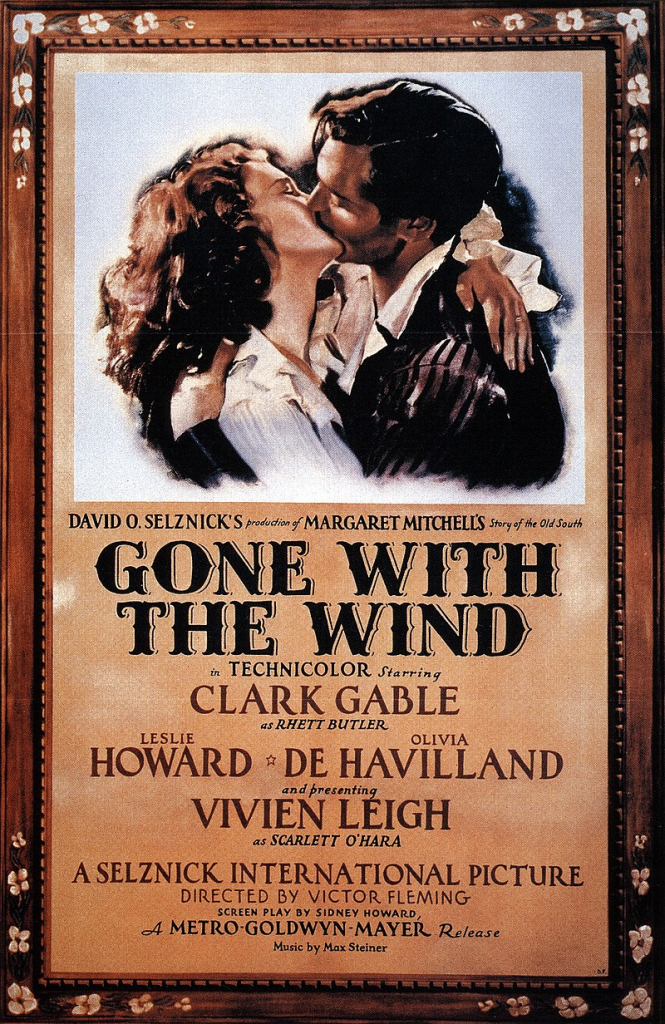

Indochine intends to be the French Gone With The Wind, a story of romance and separation, told against the backdrop of a ruinous war.

The French, of course, have their own ways of approaching such epic topics, and this movie is heavier on boudoirs and chic, lighter on bluster and battle, than our North American classics.

The French are really good at translating any tragic history into a relationship between men and women.

Indochine is also curiously inconclusive, leading up to a final meeting that never takes place.

There are many good things in this film, not least the sense of time and place:

French Indochina, later Vietnam, from the years of colonial calm to the days when the French withdrew and the beautiful country became an American trauma.

This period is largely seen through the eyes of the owner of a French plantation (Catherine Deneuve), her adopted Vietnamese daughter (Linh Dan Pham) and the daughter’s son, who is raised mostly in France by Deneuve after the mother becomes a revolutionary.

There is always something bittersweet and decadent about the dying days of colonial regimes.

The old customs have outlasted their times, and yet people go through the motions, their manners and folkways reflecting a certain stubborn pride.

They are yesterday’s people, not ready to admit it.

You get that feeling in films like White Mischief and A Passage to India and you get it here, too, as the Deneuve character strides fearlessly among her plantation workers, who may, for all she knows, be Communists preparing an uprising.

She is protected by the invisible shield of decades of French rule.

Her society is a decadent one.

She looks cool and elegant, and is dressed in understated tropical chic, but from time to time she has a Chinese retainer prepare her an opium pipe, and she is not above a sudden rush of passion with a handsome young French Naval officer (Vincent Perez).

He, alas, then falls in love with Deneuve’s beautiful young adopted daughter, and betrays the values of his officer class to embrace the rising tide of anticolonial rebellion.

The photography is the star of this movie.

As the two young lovers run away, hoping to hide themselves in the countless islands of a secret lake, a vast long shot shows their boat as a speck surrounded by magnificent landscape.

Many other shots show an architecture in harmony with the land and the climate, the outdoors sensed from indoors, the walls and windows slatted or curtained so that all life seems partly exhibitionism.

Through this film, Deneuve drifts like an angel.

She is as beautiful as ever, in the role of a lifetime – she spans decades, yet never ages, and the problem is not to make her seem young for the early scenes but old enough for the later ones.

Her serenity in the face of crisis is perhaps too perfect:

A grittier, earthier woman might have connected better with the realities of the country.

Here we get a Scarlett in her gowns but not a Scarlett who grubs for potatoes.

The screenplay does the film no favors.

It is long and discursive and not very satisfying.

After a grand melodrama like this, we expect an ending more satisfactory than the epilogue in Geneva, with Deneuve and her grandson awaiting the daughter and the Vietnamese revolutionary committee.

Of course, the story of Vietnam did not end at that point, and so perhaps the story of this movie cannot either.

Indochine is an ambitious, gorgeous missed opportunity – too slow, too long, too composed.

It is not a successful film, and yet there is so much good in it that perhaps it’s worth seeing anyway.

The beauty, the photography, the impact of the scenes shot on location in Vietnam, are all striking.

But the people seem to drift and waver in their focus.

The film seems to suggest that the French still do not quite understand what happened to them in Vietnam.

Well, they’re not alone.

You have to forget this man, Lili.

I’ll never understand French love stories.

They’re all about madness, fury, suffering.

They’re similar to our war stories.

You know the secret.

I’ve told you already.

Yes, I know.

Indifference.

The French ideology of freedom and equality was completely absent in French colonial rule, specifically Indochina.

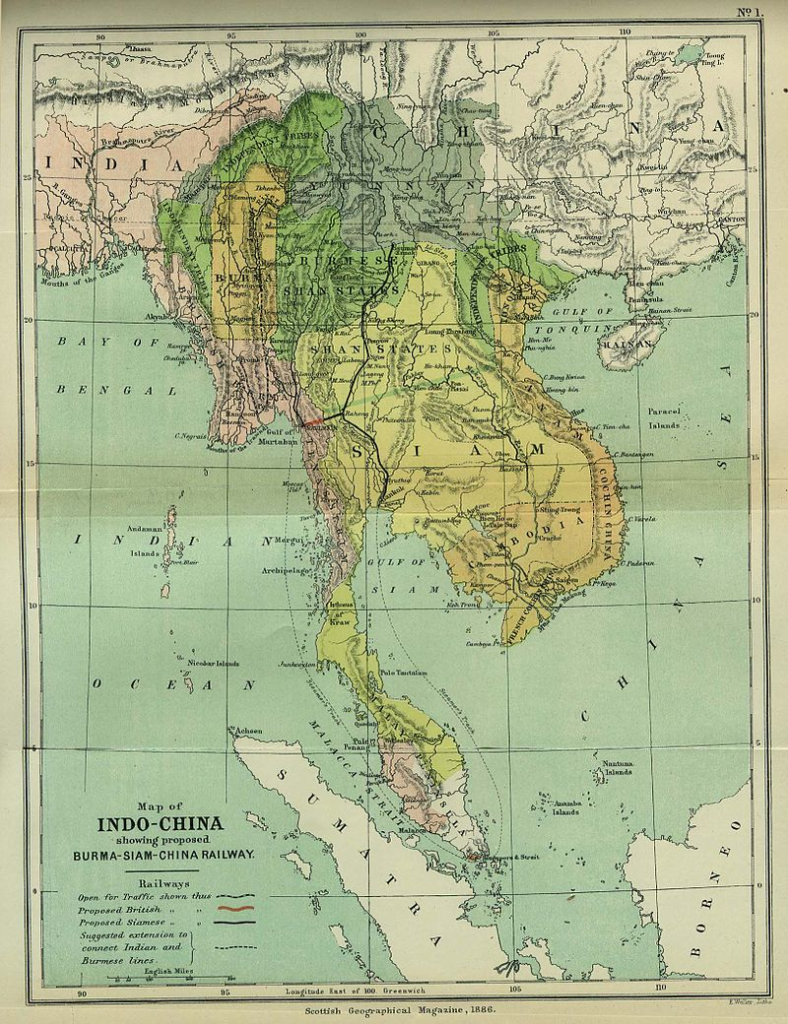

In the early 20th century before World War II, the French colonized the Indochina region, known today as Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos.

During their rule, the military and police forces emphasized the importance of their empire, taking any and all means to defend it.

The film Indochine addresses the exploitation of native subjects in Indochina around 1930, and focuses on the transformation of the region under a political revolution.

Indochine is a film set in 1930 French Indochina revolving around Éliane, a wealthy French rubber farm owner, Camille, a Vietnamese princess adopted by Éliane, and Jean-Baptiste, an officer in the French Navy.

Eliane and Jean Baptiste have a hidden romance in the beginning of the film, but after Camille is almost killed by a misdirected bullet, the story shifts to Camille and Jean-Baptiste.

Camille believes Jean Baptiste saves her life and after Jean Baptiste is reassigned to a remote post on the coast, Camille leaves everything behind to find Jean Baptiste.

When Camille is saved by Jean Baptiste, she discovers the horrors of French rule and revolts, killing a French Navy officer and escaping with Jean Baptiste.

The film does a fantastic job portraying the cruelty of French rule and their mistreatment of natives, lack of compassion, and the complete absence of “equality” when dealing with the Vietnamese population.

Although Eliane and Jean-Baptiste save Camille and often help natives, they too have moments of exploitation, showing their true backgrounds.

Five scenes in the film stand out as best representing French Indochina and the role race and power played in colonial rule.

“The prince Nguyen, his wife, and I were inseparable.

Maybe this is what youth is all about.

Believing the world is made of inseparable things.

Men and women, mountains and plains, human beings and gods, Indochina and France.”

Éliane says this in the opening scene when she is being driven by her Indian driver to her estate and plantation.

She is discussing the relationship between France and Indochina, and the imperative role it plays in the shape of her country.

In this scene, she is wearing pristine clothing in her expensive car, being driven through her rubber farm, watching all the Vietnamese workers producing rubber for her.

Throughout the film, there are rarely scenes where native people in the background are seen smiling or lively.

The only times any natives look healthy are scenes including royalty or elites.

In much the same manner as Indochine, vlogs about Vietnam all seem to focus on the wealthy and privileged foreign traveller rather than the locals who make up the bulk of the nation the foreigner is visiting.

When Éliane is saying France and Indochina are inseparable, she is only considering her French perspective, a common aspect of colonial ideology.

Even for her own daughter, Éliane often shows delusion when it comes to how white colonists see Vietnamese people.

There is a scene where Éliane is informed that her daughter Camille is being verbally attacked for being Vietnamese, but she doesn’t seem to be too concerned.

Even though Camille was raised by a wealthy French woman, society still views her as contaminated and lower class.

Another significant scene that uncovers the French officials’ true nature is when Jean-Baptiste sets fire to a native family’s boat.

Jean-Baptiste’s Navy vessel finds a small wooden boat in the delta after an 8 pm curfew and even though everyone else on the Navy ship thinks it is a genuine mistake, Jean Baptiste orders a sailor to light the Vietnamese boat on fire.

When they are sailing away from the fireball on the water, a sailor confronts Jean Baptiste:

Sailor:

“They’ll drown!

Are you proud of yourself?

Are you proud of your victory?”

Jean Baptiste:

“I followed the rules.

You can have generosity and leniency.

No one will get inside my head and steal my soul, no one!

Not even eternal Asia, no one!”

This encounter revealed Jean Baptiste’s character as the stereotypical colonial official, showing no empathy or compassion for native deaths.

“I followed the rules” is a common psychological mindset where shifting blame is simple if one didn’t actually make the decision, but rather followed an order.

This is prevalent in war, and of course imperialism, making accountability for actions far more vague and impossible.

Jean Baptiste also alludes to Asia having a soul of its own.

Europeans viewed outsiders as uncivilized and wild, and being further from the homeland can alter someone’s perspective of the world.

This concept was introduced by Joseph Conrad in Heart of Darkness, where the protagonist spirals into madness when he sails further into the Congo.

Indochine addresses the same concept and uses it as an excuse for Jean Baptiste to potentially kill an innocent Vietnamese family.

This lack of compassion was apparent in most of the film, but usually not by Éliane.

As discussed earlier, Éliane does have a view of the world where France and Indochina are inseparable because they mutually help one another.

This, however, is a mindset ingrained and innocent to her.

Later in the film, her rubber factory is set on fire and all her workers are outside refusing to return:

Head worker:

“They set fire.

It’s not an accident.

We couldn’t stop the fire.

All the rubber burned.”

Éliane: “When can we get back to work?”

Head worker: “Tomorrow, I think.”

Éliane: “Why not now?

Head worker: “They don’t want to go inside.

They say they’ll be shot.”

Éliane: “By whom?”

Native: “Boom, danger! No work!”

Éliane is clearly outraged by not only the fact that her plantation is ablaze, but also that her Vietnamese workers aren’t risking their lives for her money.

She shows absolutely no concern for the natives and instead of trying to extinguish the fire, she runs into the factory to show it is temporarily safe.

Of course the workers don’t really have a say so they follow her into the building with fear and despair.

The French had different stereotypes for certain ethnicities.

Indochinese people in particular were considered to be weaker but smarter, so during the war they often had background assistant work.

This film shows how Éliane and French officials felt physically superior to the workers and would often manhandle them into groups.

The pivotal scene in the film is when Camille shoots the Navy officer in the head.

Camille escapes Saigon to find Jean Baptiste and during her journey, she meets a Vietnamese family of four.

After running through the countryside encountering endless natives struggling to survive, she finally finds Jean Baptiste at a slave auction.

The French call it a working post, but earlier in the film an officer explicitly states it is a slave auction for Vietnamese workers.

After Jean Baptiste identifies Camille, Camille sees Sao, the mother, and the rest of the family dead in chains on the water.

Camille is horrified and when the Navy tries to capture her, she shoots the head officer in the head and escapes with Jean Baptiste.

What is interesting in this scene is the conversation between the French officials prior to Camille’s arrival.

The French officials’ main fear is a revolt and riot, which they believe would crumble the Empire.

This was a legitimate fear imperialists had when colonizing new lands.

It was apparent in many other colonies in Asia and Africa.

The final scene is about Camille’s former husband’s statement to his mother.

After deciding that he will leave Saigon to fight for Vietnamese freedom, he tells his mother:

“Camille is free.

It’s her life and she doesn’t owe anything to anyone.

Obedience made slaves out of us.

The French taught me the words “freedom” and “equality.”

That’s how I’ll fight them.”

This quote is the only time French ideology is explicitly addressed in the film and fascinatingly by a Vietnamese native talking about fighting against France.

He understands the hypocrisy of French ideology, and sees that it is only freedom and equality for themselves.

A passage in Race and War in France states:

“Colonial subjects, the thinking went, owed France a “blood tax” in return for the privilege of living under enlightened French rule.”

The French believed their colonial rule itself was a way of helping the natives, so freedom and equality were granted to them under enlightenment.

It didn’t matter to the French whether the Indochina natives were equal to them, but rather the natives received guidance to become more civilized.

Camille’s husband realizes how absurd French ideology is, so he ridicules the French by saying true freedom and equality will destroy French colonies.

These scenes in Indochine show how French ideology was completely disregarded and contradicted in French Indochina.

The film addresses many issues regarding exploitation, racism, and inhumane practices by European imperialists in their colonies, and how they contributed to their eventual downfall.

Indochine is narrated by Éliane Devries (Catherine Deneuve), a woman born to French parents in colonial Indochina.

It is told through flashbacks.

In 1930, Éliane runs her and her widowed father’s large rubber plantation with many indentured laborers, whom she casually refers to as her coolies.

She divides her days between her homes at the plantation and outside Saigon.

She is also the adoptive mother of Camille (Linh Dan Pham), whose birth parents were friends of Éliane‘s and members of the Nguyên Dynasty.

Guy Asselin (Jean Yanne), the head of the French security services in Indochina, courts Éliane, but she rejects him and raises Camille alone giving her the education of a privileged European through her teens.

Éliane meets a young French Navy lieutenant, Jean-Baptiste Le Guen (Vincent Pérez), when they bid on the same painting at an auction.

She is flustered when he challenges her publicly and surprised when he turns up at her plantation days later, searching for a boy whose sampan he set ablaze on suspicion of opium smuggling.

Éliane and Jean-Baptiste begin a torrid affair.

Camille meets Jean-Baptiste by chance one day when he rescues her from a terrorist attack.

Believing him to have saved her life, Camille falls in love with Jean-Baptiste at first sight, while Jean-Baptiste has no inkling of Camille‘s relation to Éliane.

When Éliane learns of Camille‘s love for Jean-Baptiste, she uses her connections with high-ranking Navy officials to get Jean-Baptiste transferred to Haiphong.

“And I didn’t know.

I hadn’t wanted to see, that she was in love, the way one loves the first time.

Nothing would stop her.“

Jean-Baptiste angrily confronts Éliane about his transfer during a Christmas party at her home, resulting in a heated argument where he slaps her in front of his fellow officers.

For his transgression, Jean-Baptiste is sent to the notorious Dragon Islet (Hòn Rồng), a remote French military base in northern Indochina.

Éliane allows Camille to become engaged to Thanh (Eric Nguyen), a pro-Communist Vietnamese boy expelled as a student from France because of his support for the 1930 Yên Bái Mutiny.

A sympathetic Thanh allows Camille to search for Jean-Baptiste up north.

Camille travels on foot and eventually makes it to Dragon Islet, where she and a Vietnamese family she travels with are imprisoned alongside other labourers.

When Camille comes across the sight of her travelling companions brutally tortured and murdered by French officers, she attacks a French officer and shoots him in the struggle.

Jean-Baptiste defies his superiors to protect Camille in the ensuing firefight.

The two set sail and escape Dragon Islet as outlaws.

After spending several days adrift in the Gulf of Tonkin, Camille and Jean-Baptiste reach land and are taken in by a Communist theatre troupe, who offers the couple refuge in a secluded valley.

After several months, Camille has become pregnant with Jean-Baptiste’s child, but are told they must vacate the valley out of safety.

Thanh, now a high-ranking Communist operative, arranges for the theatre troupe to smuggle the lovers into China.

Guy attempts to use operatives to quell the growing insurrections by labourers and to locate Camille and Jean-Baptiste, without success.

Camille and Jean-Baptiste‘s story becomes a celebrated legend in tuong performances by Vietnamese actors, earning Camille the popular nickname “the Red Princess“.

When the couple nears the Chinese border, Jean-Baptiste takes his and Camille‘s newborn son to baptize him in a river while she is asleep.

After christening the baby Étienne, he is ambushed and apprehended by several French soldiers.

A distraught Camille evades capture and escapes with the theatre troupe, while French authorities remand Jean-Baptiste to a Saigon jail and hand Étienne over to Éliane.

After some days in prison, Jean-Baptiste agrees to talk if he can first see his son.

The Navy, which has authority over the case and refuses to subject Jean-Baptiste to interrogation by the police, plans to court-martial Jean-Baptiste in Brest, France, to avoid the public outcry that would likely arise from a trial in Indochina.

Jean-Baptiste is allowed a 24-hour visitation with Étienne before being taken to France.

He goes to see Éliane, who lets him stay with Étienne at her Saigon residence for the night.

The next day, Éliane finds Jean-Baptiste dead in his bed with a gunshot to his temple, a gun in hand, and an unharmed Étienne.

Outraged, Éliane tells Guy she suspects the police murdered him, but Guy‘s girlfriend tells Éliane that the Communists may have killed Jean-Baptiste to silence him.

With no evidence sought for either suspicion, Jean-Baptiste‘s death is ruled a suicide.

Camille is captured and sent to Poulo Condor – a high security prison where visitors are not permitted and not even Éliane or Guy can help free her.

After five years, the Popular Front comes to power and releases all political prisoners, including Camille.

Éliane reunites with Camille, but she declines to return to her mother and son, choosing instead to join the Communists and fight for Vietnam’s independence.

Camille reasons she does not wish for her son to know the horrors she has witnessed.

She tells her mother that French colonialism is drawing to an end.

Taking Étienne with her, Éliane sells her plantation and leaves Indochina.

In 1954, Éliane finishes telling her story to a grown Étienne (Jean-Baptiste Huynh).

They have both come to Switzerland, where Camille is a Vietnamese Communist Party delegate to the Geneva Conference.

Étienne goes to the negotiators’ hotel intending to find his birth mother, but it is so crowded with people that he is not sure how Camille can find or recognize him.

He tells Éliane he sees her as his mother.

As the film concludes, an epilogue notes the next day, French Indochina becomes independent from France and Vietnam is partitioned into North and South Vietnam (leading, eventually, to the Vietnam War).

From Thach Bich wharf, sampans sail to Sunshine Valley.

Beneath the clear cool water is a rich and lively fauna.

Thung Nang still retains its wild features.

Relax and feel comfortable in this quiet and pleasant space.

When the boat is brought into the cave, you may feel cool.

The ceiling of the cave is very low, with stalactites of various shapes.

In front of the cave are luxuriant reed bushes.

Here, anchor the boat, rest, take pictures, and admire the beautiful scenery.

The large valley still retains the pristine features that nature intended.

Should fortune favour, perhaps you may see flocks of white storks surveying the wetland.

Crossing a waterway with whispering rice fields on both sides, overlapping mountains, you will pass Voi Temple.

Continuing the journey, you will come to Thung Nang Cave (100 metres long), wherein is Thung Nang Temple.

The Temple was built in a quiet space, the back of the temple leaning on the sacred mountain, an ideal place to worship God.

After Thung Nang, on the way back, visit Voi Temple.

Voi Temple, built hundreds of years ago, of stone, is famous for its elaborately carved altars.

If you have time after the boat trip, follow the road leading southwest from the boat dock for about 2km to visit the cave-pagoda of Bich Dong, or “Jade Grotto“.

Stone-cut steps, entangled by the thick roots of banyan trees, lead up a cliff face peppered with shrines to the cave entrance, believed to have been discovered by two monks in the early 15th century.

On the rock face above, two giant characters declare “Bich Dong“.

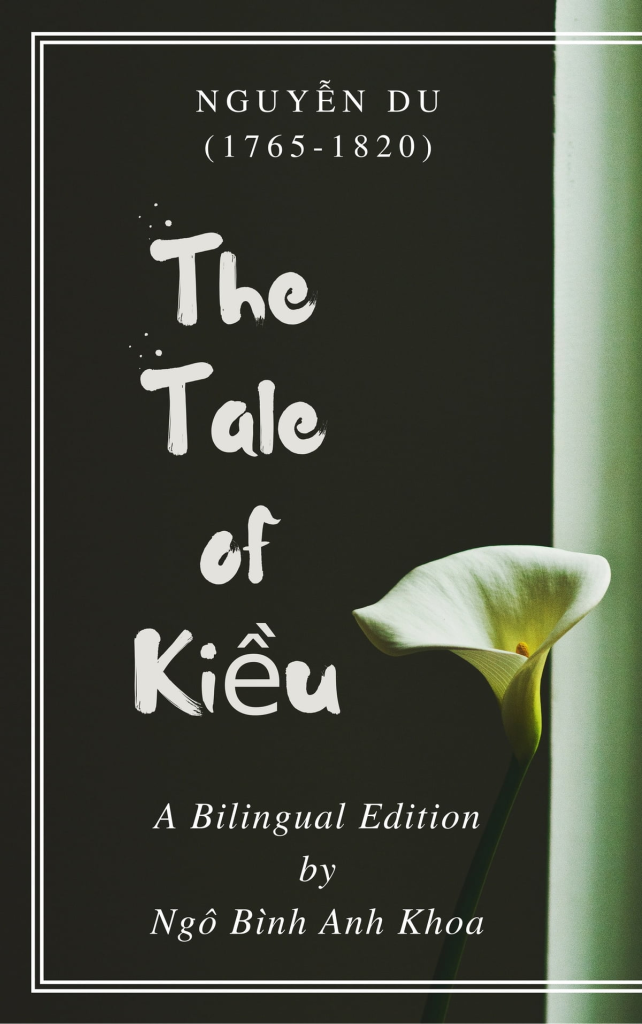

The story goes that they were engraved in the 18th century by the father of Nguyen Du (author of the classic Tale of Kieu), who was entrusted with the construction of the complex.

The cave walls are now scrawled with graffiti, but the three Buddhas sit unperturbed on their lotus thrones beside a head-shaped rock which purportedly bestows longevity if touched.

Walk through the cave to emerge higher up the cliff, from where steps continue to the third and final temple and viewpoint over the waterlogged scene.

Bich Dong means “green cave“, the name given to the Cave by Prime Minister Nguyen Nghiem, the father of the great poet Nguyen Du, in 1773.

The ancients called it “Nam Thien De Nhat Dong“, which means “the second most beautiful cave in the South” [behind Huong Tich Cave in Huong Son].

Bich Dong consists of a dry cave located halfway up the mountain and a water cave that pierces the mountain.

In front of the water cave is a tributary of the Ngo Dong River winding by the side of the mountain.

Across the river are rice fields.

Xuyen Thuy Cave is the dark and flooded cave located along the length of the Bich Dong massif.

Xuyen Thuy resembles a semicircular stone pipe about 350 metres long winding from east to west.

The average width of Xuyen Thuy Dong is 6 metres, the widest place is 15 metres.

The ceiling and walls of the cave are usually flat, creating a large stone slab like a dome, a semi-circle with various shapes.

The entrance to Xuyen Thuy Cave is at the back of the mountain, opposite the road to Bich Dong Pagoda.

At the end of the journey through the water cave, visitors can climb the mountain to reach the dry cave and Bich Dong Pagoda.

Bich Dong Pagoda is an ancient temple, built at the beginning of the Hau Le dynasty.

Inside the pagoda, there is a large bell cast during the reign of King Le Thai To, and the tombs of the monks who built the pagoda.

In 1705, there were two monks Tri Kien and Tri The.

Both monks were devout and wanted to go to many places to spread Buddhism and build temples.

Seeing that Bich Dong Mountain has a beautiful terrain and already had a pagoda, the two monks decided to stop, repair the old pagoda by themselves, donate money to rebuild it into three pagodas, and to remain here to lead religious lives.

In 1707, the two monks cast a large bell, which still hangs in Dark Cave.

The Minh Bia song written on the bell is considered the inscription of the Pagoda’s stele, written in Chinese characters, including the passage:

Been up that mountain

Blessed, have grace

Open the mountain, cut the rock,

Pure Qi handed down

During the reign of Le Hien Tong (1740 – 1786), the pagoda was restored and expanded to include Lower Pagoda, Trung Pagoda, and Upper Pagoda, spread out across three mountain floors.

In the year of the Horse (1774), Lord Trinh Sam visited the Pagoda, looking out at the panorama of mountains, caves, rivers, fields and trees, the Pagoda seemed to converge on the green background, so he named the pagoda Bich Dong (green pearl grotto).

Bich Dong Pagoda is an ancient architectural work, so like other temples built of ironwood, the roof is tiled with curved corners.

The blade, the shape of a phoenix’s tail, makes the roof undulating, flexible like tidal waves, looking like a spectacular dragon boat floating on water or like two wings of a bird flying up to Heaven.

Four mountains around the four seasons

The boat gently paddles racing

Waves crashing around the cave

Clouds pour over the temple scene

Bich Dong Pagoda was built in the style of “three“:

Three non-contiguous buildings, three levels along the mountainside, based on the mountain in position from low to high into three separate pagodas:

Lower, Middle and Upper.

The Lower lies at the base.

The Middle is reached by stone-cut steps, entangled by the thick roots of banyan trees, that lead up the face of the cliff.

Enter the Dark Cave.

Walk through the Cave to emerge higher up the cliff, from where steps continue – you will need a flashlight/torch – to the third and final Upper Temple, from whence you can gaze at the universe below.

The unique thing of Bich Dong Pagoda is that the mountains, caves and pagodas complement each other, and are hidden among the great green trees, making the pagoda blend in with the exotic natural scenery.

The panorama is a picture of majestic mountains and forests, inlaid with a bas-relief of ancient pagodas.

It was built on a high mountainside, where beneath lies Xuyen Thuy Cave.

From Trung (Lower) Pagoda, up six metres higher, is the Dark Cave, silent, solemn, slightly inclined to the east.

The way up to Dark Cave is almost vertical.

Go under the bridge and the cave gate looks like a rainbow.

Above the cave door hangs the large bronze bell cast by the monks Tri Kien and Tri The in 1707.

Dark Cave is a long, wide space with electric lighting, creating the aura of a petrified fairy world.

Near the door of Dark Cave are the statues of Buddha Amitabha, Manjushri Bodhisattva, and Guanyin Bodhisattva.

The three Buddhas sit on lotus thrones beside a head-shaped rock.

The rock purportedly bestows longevity if touched.

So, touch the rock, live long, and prosper.

Inside the entrance of the Dark Cave, on the left, is a small cave, paying homage to Quan The Am Bodhisattva.

Within this small cave are stalactites like turtles and two strange rock blocks that sound like a muzzle, one rock the bass, the other its echo.

Dark Cave is a natural temple, where one may hear the whisper of that quiet voice within.

One kilometre north of Bich Dong is beautiful Tien Cave, which is actually three large and wide high caves.

The ceilings of the caves have many stone veins, stalactites drooping with colourful sparkles, looking like big tree roots.

There are many bats and birds on the ceiling.

From the outside, the cave looks like a magnificent castle.

The changes of nature have created interesting shapes of stalactite in the shapes of trees, fairies, elephants, lions, tigers, iguanas, dragons, eagles, and colourful clouds.

The stone blocks in the cave, when tapped, will create many strange and wondrous sounds.

Three kilometres north of Tam Coc, Mua Cave is not, in fact, worth the diversion, but rather it is the pagoda and the viewpoint from the hillside above the Cave that makes the journey worthwhile.

A punishing 467 steps zigzag upwards from beside the cave entrance to a lookout across vast karst mountain scape.

Sadly – (or fortunately depending upon your point-of-view) – the land around the entrance has been developed into a resort, so, “naturally“, there is an overpriced restaurant on site to buy refreshments

This is an artificial tourist area with services such as mountain climbing, weekend getaways and conferences.

According to legend, Mua Cave was a place for performing arts, dancing and singing of the court ladies of the Tran dynasty.

Descriptions of Vietnam, through the tales of Swiss Miss and my own research to tell those tales, compel me to one day visit this nation.

Maybe even work there.

Vietnam is chronically short of language teachers due to its dizzying rate of economic growth (second only to China).

One of the main reasons for this growth in demand for teachers is the nation’s booming prosperity and an urgent ambition among parents for their children to master English.

Many urban Vietnamese want to learn English with a view to joining a profession such as banking or tourism or to have a chance of acceptance at institutes of higher learning overseas.

It is rumoured to be relatively easy for native speakers to get a job in Hanoi or Hoi Chi Minh City (HCMC) on the basis of a telephone interview.

Schools, it is said, will snap you up, especially if you have a bachelor’s degree and a CELTA.

Furthermore, Vietnam has low living costs and high salaries.

Often the best way to find work is to simply arrive in one of the major cities and look around.

Although Vietnam is still a one-party socialist republic (which has been accused of blocking websites and blogs that are critical of the government), it bears all the trappings (complete with garish advertising hoardings and American pop music) of a capitalist society with an expanding young middle class who invest in electronic goods, luxury items and English lessons.

Hanoi was beautiful, bustling and noisy.

HCMC (Ho Chi Minh City / formerly Saigon) is said to be a Bangkok in the making, with its sophisticated, sprawling commercial centre boasting a skyline dotted with skyscrapers – a metropolis that challenges the visitor with traffic, noise, pollution and street hassle.

Vietnam is a developing country and although the wealth of the nouveau riche classes in the cities is very visible, the countryside is still desperately poor.

The country experiences frequent power cuts and things in general don’t always work as they are supposed to.

Yet many travellers find themselves, despite the stifling heat and the torrential rains, the crowds and the pollution, delighted with the cities, packed with cheap restaurants and fantastic street food and the buzzing vibrant chaos of the night.

The senses are assaulted, the pulse races, the heart finds a rhythm and pace both soothing and searing.

The melodic voice of Trung Kien Trinh evokes the urban melancholy and yearning, music navigates life.

Vietnamese music, undying, unceasing, boasts less about bling and instead whispers and croons the emotions and lives of ordinary people.

Vagabond upper crust travellers mingle in this Communist parody of colonial capitalism.

The locals quietly survive with grace and dignity.

This is a nation of black humor and youthful energy, the daily life of today intertwined with the dangerous legacy of yesterday and the vague promise of tomorrow.

Where the damned dance with the deceased and where grief is touched by the magic of courageous tenacity and enduring elegance.

This is the Vietnam that the tourist cannot see and the traveller forever seeks.

Travelling for the foreigner, despite “Western prices” where foreigners pay substantially more than locals do for everything, despite the deception behind that charming Vietnamese smile that seeks to extract money from the gullible, is nevertheless very affordable.

Low-cost airlines fly from north to south.

Regular tourist night buses are a great way to explore the country.

The Reunification Express train runs the full length of the country (over 1,300 km).

But renting (or purchasing) a motorcycle offers the traveller both flexibility and speed, for whatever else Vietnam may lack there is no shortage of motorbikes for rent or purchase here.

Although it is technically illegal for non-residents to own a vehicle, there is a small trade in second-hand motorbikes in Hanoi and HCMC.

Look at the noticeboards in hotels, travellers’ cafés and tour agents for adverts.

So far, the police ignore the practice…..

On the whole, the cops leave the alien alone, but if you are involved in an accident it is assumed that it is the foreigner’s fault.

Being the wise woman that she is, Heidi checked over everything carefully on her and Sebastian‘s bikes before they left Hanoi.

The brakes, the lights, the horns, the helmets.

All functioning, or at least appeared to be functioning.

It is said that the roads were worse in the past then they are today, but off the main highways road conditions can be highly erratic, with pristine asphalt followed by stretches of spine-jarring potholes and plenty of loose gravel on the sides of the road.

And there is no method to the madness that passes as the rules of the road in Vietnam.

Theory is merely a mention when faced with the frenzy of the fast and furious folly that is driving in the Republic.

Drive on the right…..

In theory.

But in practice…..

Drivers swoop and swerve, dash and dodge, wherever, however they wish.

Might means right, and right-of-way.

The mere motorcycle gives away to thundering trucks and hell bound buses, with indicators and brakes forgotten while the cacophony of horns is the language of the lane.

They assume the small give way to the big, that those without a death wish are wise enough to know when to allow themselves to be forced off the road, pulling over to the hard shoulder to avoid being crushed by the behemoths bent on maximum speed and minimal delay.

Darkness is death for the unwise motorcyclist, for many vehicles lack functioning headlights or the conscience to turn them on.

Flashing headlights, contrary to the unwritten rules of most of the world, do not mean “after you“, but rather in Vietnam they mean:

“There is no way on Earth that I am stopping for you.”

So Heidi and Sebastian ride by day and seek lodgings before the sun sets.

These are modern times and the tech-savvy traveller knows the wisdom of BABA (book a bed ahead), so the day’s destination was set:

Ninh Binh, a mere two hours’ ride (in theory) from Hanoi, was the first day’s goal, a modest ambition with a side trip to the Tam Coc region.

The provincial capital of Ninh Binh is an unattractive, traffic-heavy northern town with nothing much to see.

It is one of many places in the world that are great as a base to travel from, but lacking allure to draw visitors to themselves.

Ninh Binh City is located on the right bank of the Day River, with two bridges spanning the confluence of the Van and Day rivers.

The Day plays an important role in draining the city and flows beneath the urban beauty of the two steel bridges, Non Nuoc Bo and Ninh Binh, drawing the curious into the city centre.

On the river, Ninh Phuc and Ninh Binh ports connect water traffic to the mouth of the sea.

Day River Afternoon

The floating bridge at the end of the village opens the field

The mountains are green and the eye layers are right

The water rises, pushing the boat away from the sun

The old way to the moonlight

Smoke spread sporadically on both sides of the house

Spring trees and immense clusters of water

Trying to see where my hometown is

Cloudy white, pink wings

Nguyen Du

Ninh Binh is a crossroads, a fork where rivers and roads meet.

Since ancient times, the Trang An World Heritage Site complex, in the west of the city, has been the residence of prehistoric people belonging to the Stone Age.

Since ancient times, the confluence of the Van and the Day Rivers has formed markets and a wharf.

Along with favorable traffic advantages due to the location at the intersection of main roads, these markets have developed into a major economic, political and cultural centre south of the Red River Delta.

In 1873, the French occupied Ninh Binh with the intention of making this place an urban area with many architectural works, such as Ninh Binh Citadel, Lim Bridge, Church Street, Dragon Market…..

Later, people supported the “garden without empty house” campaign, so many urban buildings were demolished.

This is why Ninh Binh has the feel of a young city with a landscape that looks new.

During the Nguyen dynasty in August 1884 during the Tonkin campaign, the allegiance of Ninh Bình was of considerable importance to the French, as artillery mounted in its lofty citadel controlled river traffic to the Gulf of Tonkin.

Although the Vietnamese authorities in Ninh Bình made no attempt to hinder the passage of an expedition launched by Henri Rivière in March 1883 to capture Nam Dinh, they were known to be hostile towards the French.

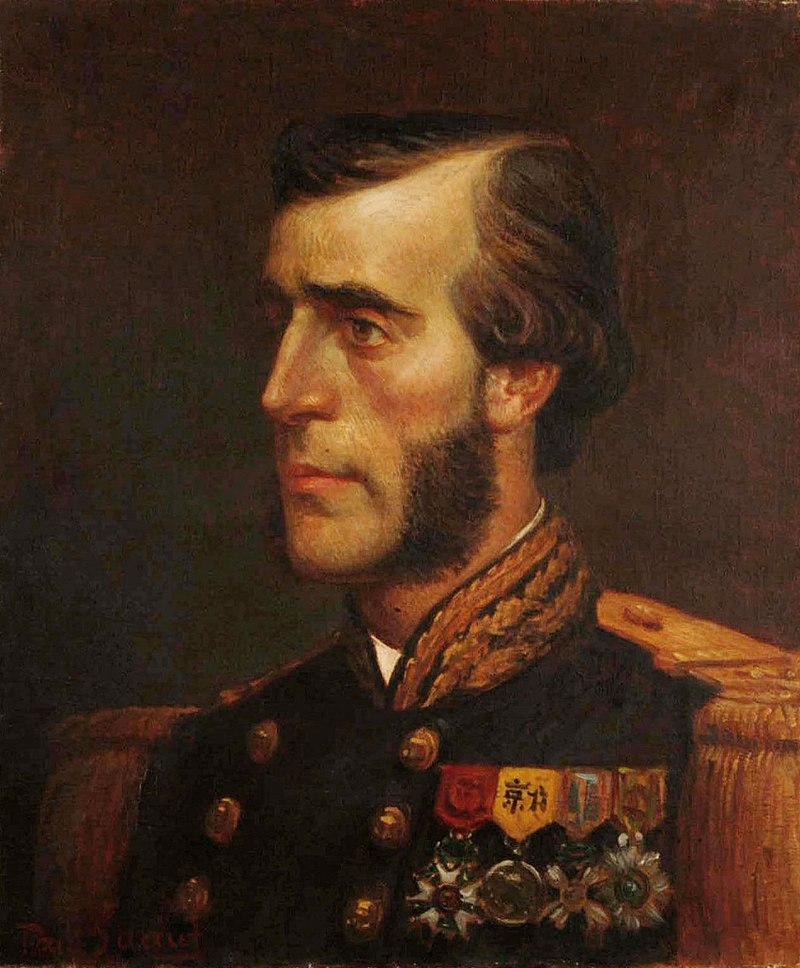

Born in Paris, Rivière entered the École Navale in October 1842.

He mustered out as a midshipman (second class) in August 1845, and saw his first naval service in the Pacific Ocean on Brillante.

In February 1847 he was posted to the South Seas naval division, to Virginie.

He was promoted to midshipman (first class) in September 1847 and to enseigne de vaisseau (ensign) in September 1849.

During the next five years he served in the Mediterranean squadron aboard Iéna (1850), Labrador (1851) and Jupiter (1852 – 1854).

Significantly, his confidential reports from this period mentioned that he seemed to be unduly interested in poetry and literature.

Rivière took part in the Crimean campaign (1854–56), serving on the vessels Uranie, Suffren, Bourrasque and Montebello.

Promoted to the rank of lieutenant de vaisseau in November 1856, he served aboard Reine Hortense during the Franco – Austrian War (1859).

In 1866 he took part in the Mexican campaign aboard Rhône and Brandon.

Clockwise from left: French assault on the fort of San Xavier during the siege of Puebla (March 1863) French cavalry capture the Republican flag during the Battle San Pablo del Monte (1863), the 1867 execution of Emperor Maximilian (1832 -1867)

He was promoted to the rank of capitaine de frégate in June 1870 and served as second officer on the ironclad corvette Thétis with the French Baltic Squadron during the Franco – Prussian War (1870).

He saw no active service in any of these campaigns.

Top left: The Proclamation of the German Empire

Top right: Henry XVII, Prince Reuss, on the side of the 5th Squadron I Guards Dragoon Regiment at Mars-la-Tour, 16 August 1870

Middle left: The Siege of Paris in 1870

Middle right: The Lauenburg 9th Jäger Battalion at Gravelotte

Bottom left: The Defense of Champigny

Bottom right: The Last Cartridges

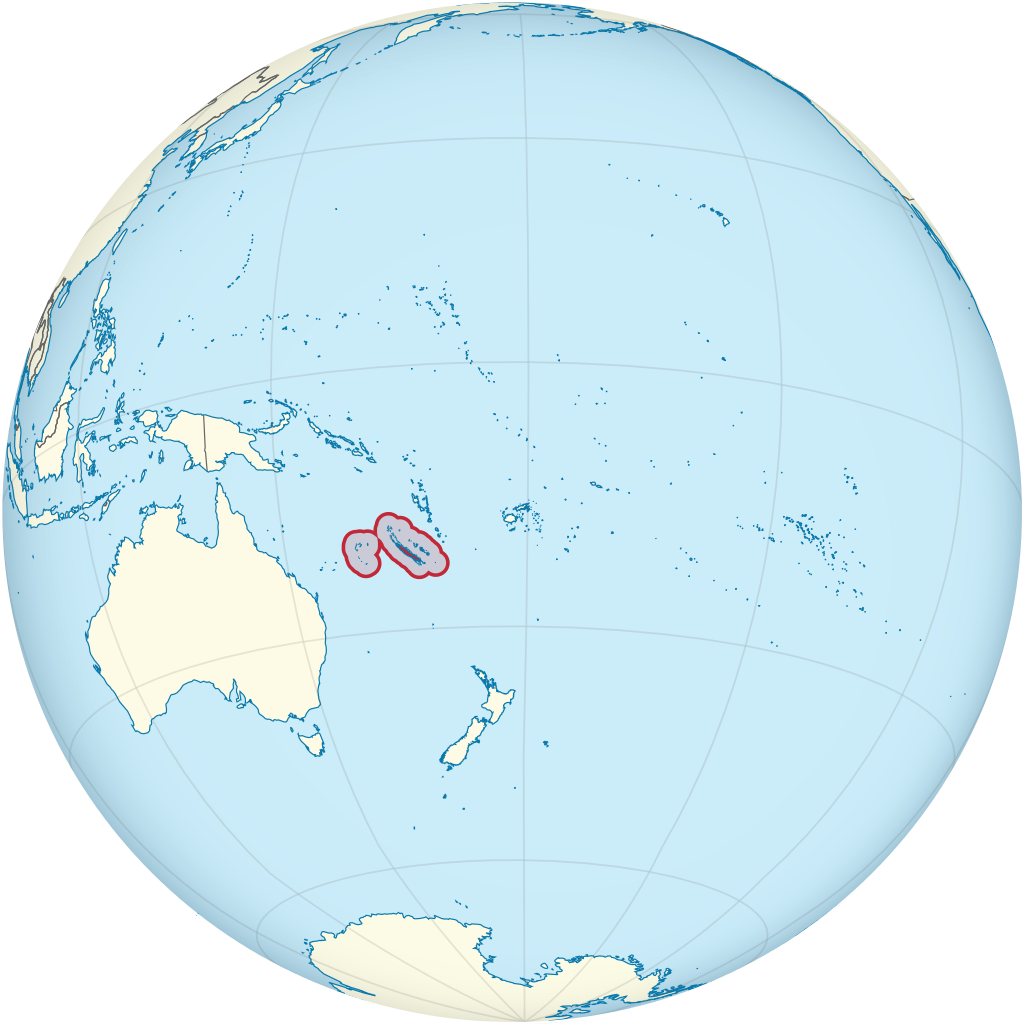

Rivière’s role in the suppression of a revolt in the French colony of New Caledonia in the late 1870s won him promotion to the coveted rank of capitaine de vaisseau in January 1880.

In November 1881 Rivière was posted to Saigon (HCMC), as commander of the Cochin China naval division.

The posting was generally regarded as a backwater that offered few opportunities for distinction.

Rivière himself saw it as an opportunity to write a literary masterpiece that would procure him membership of the Académie française.

Although Rivière spent most of his adult life as a naval officer, he was also ambitious for literary distinction.

He was a journalist for La Liberté and also had articles published in the Revue des deux mondes.

At the end of 1881, Rivière was sent with a small French military force to Hanoi to investigate Vietnamese complaints against the activities of French merchants.

In defiance of the instructions of his superiors, he stormed the citadel of Hanoi on 25 April 1882 in a few hours, with the governor Hoàng Diêu committing suicide having sent a note of apology to the Emperor.

Although Rivière subsequently returned the citadel to Vietnamese control, his recourse to force was greeted with alarm in both Vietnam and China.

The Vietnamese government, unable to confront Rivière with its own ramshackle army, enlisted the help of Liu Yongfu, whose well-trained and seasoned Black Flag soldiers were to prove a thorn in the side of the French.

The Black Flags had already inflicted one humiliating defeat on a French force commanded by lieutenant de vaisseau Francis Garnier in 1873.

Like Rivière in 1882, Garnier had exceeded his instructions and attempted to intervene militarily in northern Vietnam.

Liu Yongfu had been called in by the Vietnamese government, and ended a remarkable series of French victories against the Vietnamese by defeating Garnier’s small French force beneath the walls of Hanoi.

Garnier was killed in this battle, and the French government later disavowed his expedition.

The Vietnamese also bid for Chinese support.

Vietnam had long been a tributary of China.

China agreed to arm and support the Black Flags and to covertly oppose French operations in Tonkin.

The Qing court also sent a strong signal to the French that China would not allow Tonkin to fall under French control.