Eskişehir, Türkiye, Thursday 16 June 2022

Steve Biddulph tells a story which resonates with me every time I think of it:

Two farmers stand in the dusty yard of a property.

One is a neighbour, come to say goodbye.

The other is watching as the last of his furniture is packed onto a truck.

The farm looks bare.

Stock gone, machinery sold.

Two teenagers stand by the car.

The wife sits inside it.

Eyes averted.

The two men have farmed alongside each other for 30 years, fought bushfires, driven through the night with injured children, eaten thousands of scones, drunk gallons of black tea, and cared for each other’s wives and kids as their own.

They have shared good times and bad.

Now, one is leaving.

Bankrupt.

He will go to live in the city, where his wife will support them by cleaning motels.

“Well, I’ll be off then.“, says one.

“Yeah. Thanks for coming over.“, says the other.

“Look us up sometime.“, says the one.

“Yeah, I reckon.“, says the other.

They climb into their vehicles and leave.

While their wives will correspond for years to come, these men will never exchange words again.

So much unspoken.

So much that would help the healing to take place from this terrible turn of events.

What pain would flow out if one was to say:

“Listen, you have been the best friend a man could want.” and looked the other straight in the eye as he said it.

If they had spent a long evening together with their wives, full of “remember when” punctuated with tears and easing laughter.

If, instead of standing stiff-armed and choked, they could have had a long strong hug, from which to draw strength and assurance, as they faced the hardship their futures would bring.

The farmer leaving the land will not find the opportunity for any support, comfort or appreciation.

He twists up inside to suppress the emotions his body feels.

Self-censoring of any kind of warmth, creativity, affection or emotion.

No one feels free to be himself, to simply be.

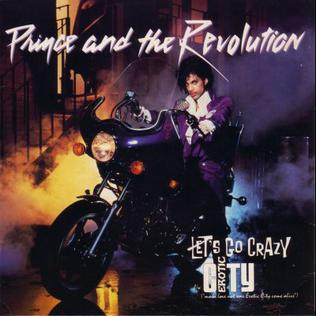

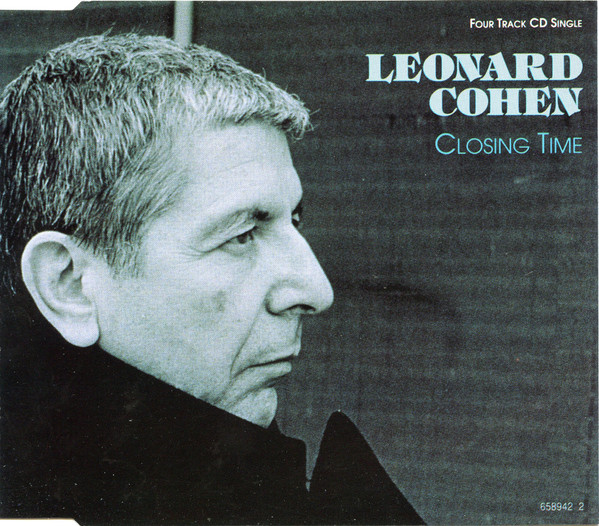

A night out with the boys – the terrible trio (joined briefly by the lovely Miss S.) of “Luck of the Irish” Paul, “the Yank that Florida forgot” Ian, and Canada Slim (a legend in his own mind) your humble blogger.

Three expats from places few, if any, of our students have ever visited, on a Saturday night in a pseudo-Irish pub named the Dublin, a watering hole with as little connection to the Irish capital as an African has with Greenland.

In an ideal world men would see each other as brothers, with good things to give and to receive.

The Xervante people of Brazil divide manhood up into eight stages of growth.

These peer groups stay very close throughout life.

They are also helped by those in the group higher up in the sequence.

Each year the Xervante hold running races for each group in turn.

These races look like a contest but they are not.

When a runner falters or trips, the others pick him up and run with him.

The group always finishes together.

It is not a race at all, though everyone puts in a huge effort.

It is a celebration of manhood – an expression of vitality.

The Xervante is a culture that has survived thousands of years by cooperation.

They don’t have to prove they are men.

They celebrate that they are men.

I wonder:

Do women feel the need to prove that they are women?

Friends offer enormous comfort.

They help to structure your time.

They show you that you belong and can be cared about.

A man who lacks a network of friends is seriously impaired from living his life, from loving his life.

Friends alleviate the neurotic overdependence on a wife or a girlfriend for every emotional need.

If a man, going through a “rough patch“, gets help from his friends as well as his partner, then the burden is shared.

If his problems are with his partner (as they often are) then his friends can help him through, talk sense into him, stop him acting stupidly and help him to release his grief.

Male friends can do these things where women cannot.

Other men know how a man feels.

Men have issues which do not have a female equivalent.

Only other men can help a man learn about the ongoing process of being a man.

Millions of women complain about their male partner’s lack of feeling, his woodenness.

Men themselves often feel numb and confused about what they really want.

This is usually attributed to the irreconcilable split between men and women – the “battle of the sexes“.

But what if men’s inarticulateness simply comes from a lack of sharing opportunities (as opposed to bullshit sessions) with other men?

If men talked to each other more, perhaps they would understand themselves better.

Perhaps they would have more to say to their female partners.

Only in the company of other men can men begin to activate themselves.

As men’s voices have a different tone, so do their feelings.

We have more than enough feelings, but they are not the same as women’s.

But where women instinctively seem to have no trouble expressing themselves, many men are not as fortunate.

We have been set up.

We are asked to be more intimate and sensitive.

However, we are still coached in the possibility of being sent to war, still expected to be tough when needed.

Because toughness is needed in this life.

Toughness is expected from a man.

We and our women folk don’t actually want men who are weaker.

Just men who can shift gears when needed.

Not an easy task.

Controlling one’s feelings is a very valuable part of being male.

It has great survival value.

And all women, deep down, count on this.

But being able to also let go of these feelings, when the time is right, is another matter entirely.

For truth be told, reserve creates reserve, unspoken fears remain unexpressed.

But banter and warmth to counter the internal struggle of loss and shame teaches us respect for pain and endurance.

We live deep within.

We speak, we listen.

There is a pressure inside that builds up over a very long period of time.

We are tense, we are numb, because we have held ourselves back.

Women have their own pain and so cannot always provide what a man needs.

Failing to express the depth of what a man feels leads to a shutdown in the full spectrum of emotions – anger, fear, warmth and love.

Passion is gone.

Passion is needed.

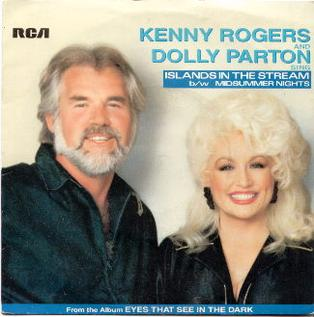

Dearly beloved, we are gathered together to celebrate that thing called Life.

Men gather together to have fun.

Noisy, energetic, affectionate, ribald, accepting, cautious, but free from respectability or restraint.

We are harsh with one another.

We are zany.

We call out each other for the BS we all inherently have.

Character is built this way.

We are islands of seriousness in an ocean of fun.

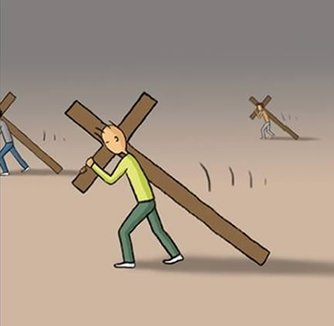

Our lives are eased, stabilized and supported by these friendships.

We each have our own cross to bear, but it is comforting to know that others care burdens equal to our own.

That we are not alone in suffering and sorrow.

Of course, the question arises:

What are we doing with our lives?

We sip our drinks, and I am reminded of Ronald Gross’ The Independent Scholar’s Handbook:

“Ronald, I have always made a respectable living, but I have not been willing to give up my life to getting the kind of money with which you can buy the best things in life.

I am stuck in business and routine and tedium.

I must live as I can.

But I give up only as much as I must.

For the rest, I have lived, and always will live, my life as it can be lived at its best, with art, music, poetry, literature, science, philosophy and thought.

I shall know the keener pleasures, as long as I can and as much as I can.

That is the real practical use of self-education and self-culture.

It converts a world which is only a good world for those who can win at its ruthless game into a world good for all of us.

Your education is the only thing that nothing can take from you in this life.

You can lose your money, your wife, your children, your friends, your pride, your honour and your life, but while you live you cannot lose your culture, such as it is.“

Sometimes I think that ESL teachers are the plongeurs (the dishwashers) of language.

Ours is a job that offers little prospects beyond more hours that may generate more trivial amounts of money spent in more frivolous ways.

Our lives are intensely exhausting, though we must pretend to possess an energy we do not really feel.

To be enthusiastic, we act enthusiastic.

But the more honest an ESL teacher is, the more he admits that this energy is merely a generated sham to encourage those who cannot learn that they should nevertheless try.

We try to bring hope to the hopeless and happiness to the hapless, even though we know that many of those in our charge possess hardly a whit (or wit) of skill or interest in our struggles to somehow educate them.

Ours is the sort of job a lazy man thinks enviable, only to soon realize that advancement (what little there might be) requires effort even in this endeavour.

This is the sort of job an alcoholic might consider doing in his brief moments of sobriety.

All that is required is to speak words that sound plausible for the monies of the gullible.

We avoid penury and injury by pretending wisdom and intelligence.

Happily, some of us need not pretend.

But low as we are and as far removed as we may be from the sacred groves of Academe, we possess a perverse pride that sustains us.

It is the pride of the drudge.

We are intellectual beasts of burden, oxen dragging ploughshares through the barren fields of blissful ignorance, seeking a harvest that can maintain us.

We will teach anyone anything if it is sought and taught in English.

Our capacity to continue is our only virtue.

Our brilliant ruse that we can teach the improbable to the impossible is our only vice.

Some of us when school shifts end stagger bone-weary to our bowers, turn on our laptops and continue to teach online for as long as there are students willing to learn in the remaining hours before midnight.

Few would ever demand our services past midnight or prior to dawn, but were there such denizens of the night, an ESL teacher would fight exhaustion and keep teaching till his last coherent thought fades into unconscious slumber.

Those with intimate companions seek solace and silence in the arms of amnesia.

Those without such comforts seek release in other ways.

Some to the quiet dullness of apartment hovels we laughingly call home.

Others when propriety allows to the taverns they hie.

Truth of character lies at the bottom of a glass, coaxed cleverly from the neck of a bottle, spoken loudly from the courage of uninhibited spirits.

We are not alcoholics, but not for lack of trying.

Men who teach are frustrated by women who share the profession, such obstinate virtue, minds of metal encased in bodies made for sin.

We speak about the unspeakable, professing love for the unlovable, draining hope’s last drop from transparent glasses.

We wish to quarrel but that requires effort.

So we shout and we joke and we drink and the smokers smoke and the non-smokers choke and we make love to the moment.

We stagger home aware of our deficiencies and return to anonymous apartments and invisible lives.

The expat ESL teacher knows that the natives make less and work more, but we grumble nonetheless ungratefully.

Oh, woe is the world of the wandering scholar!

Oh, weep for the women who wonder why we are driven so!

We seek to belong where we do not and flee from the places where we once did.

We tell ourselves we are happy.

Occasionally our lies convince even ourselves.

Morning comes and the bones ache and the eyes itch and the mouth is dry.

Another day is dawning.

I recall what words of wisdom remain from the haze of the evening.

We spoke of colleagues, both loved and loathed.

We spoke of students, the delightful and the despised.

We spoke of Eskişehir and sought to justify our presence here.

We spoke of what it isn’t to find feeling for what it is.

It is neither Istanbul nor Ankara with their crowds and their cost and their cacophony of chaos and cars.

Tourists rarely come here, for what might attract them is quickly seen and forgotten.

It is neither Kars nor Konya where conservatives demand lip service over the freedom of thought and expression that is every person’s due, for Eskişehir is a university town that leans liberally left.

In Konya, women scurry.

In Eskişehir, women strut.

Away from the dark thoughts of the drinkers of the Dublin.

Morning has broken and dawn recalls the places that once were familiar.

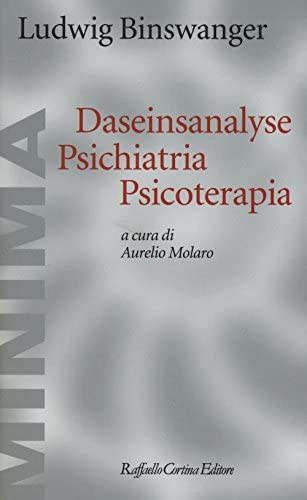

And for reasons not immediately clear I think of Kreuzlingen, Switzerland…..

Kreuzlingen, Switzerland, Thursday 30 December 2021

First, let me explain myself.

I believe that travel should bring people together.

We travel to have enlightening experiences, to meet inspirational people, to be stimulated, to learn, to grow.

Travel humbles you, enriches you, shapes your world view, and sometimes activates you into doing your part in making the world a better place for everyone.

We better ourselves by observing others.

We learn about ourselves by observing others and by challenging ourselves to see beyond our individual selves.

By learning from our travels and bringing these ideas home, we make our homes even stronger.

With thoughtful travel comes powerful lessons.

We need to travel purposefully, to learn with an open mind, to consider new solutions to old problems, to come home and look at ourselves more honestly, and help our society confront its challenges more wisely.

I have been back in Switzerland two days and I am already ready to leave, for I share the sentiments that Lord Byron once did:

“Switzerland is a cursed, selfish, swinish country of brutes in the most romantic region of the world.“

And of the places in this land that reflect the character of the Swiss without the romance of their geography, Kreuzlingen is the epitome of what I dislike the most here.

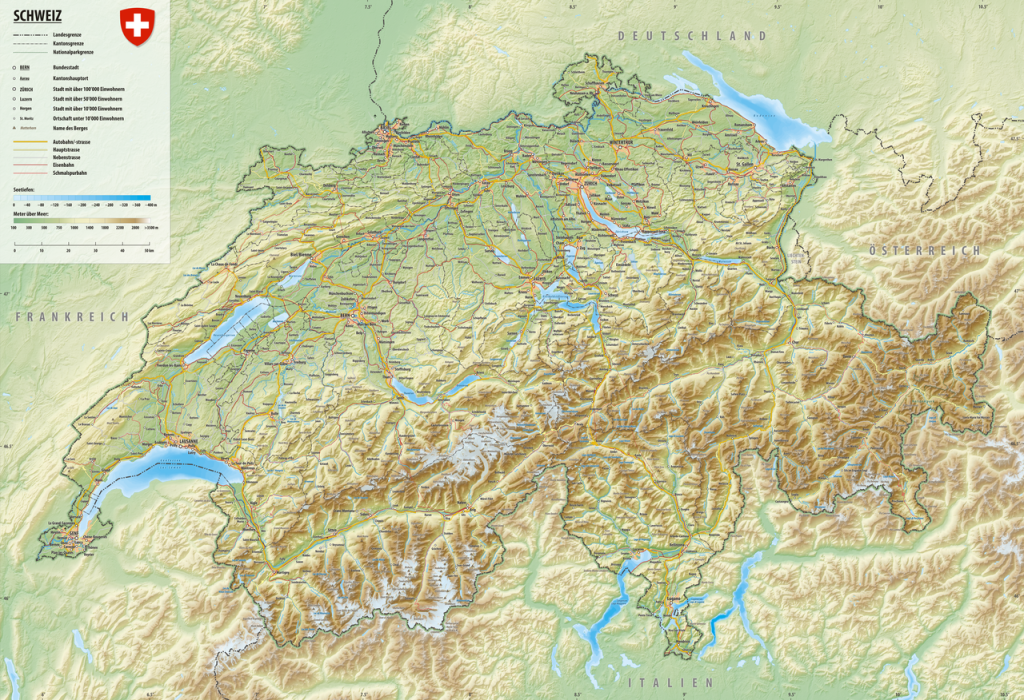

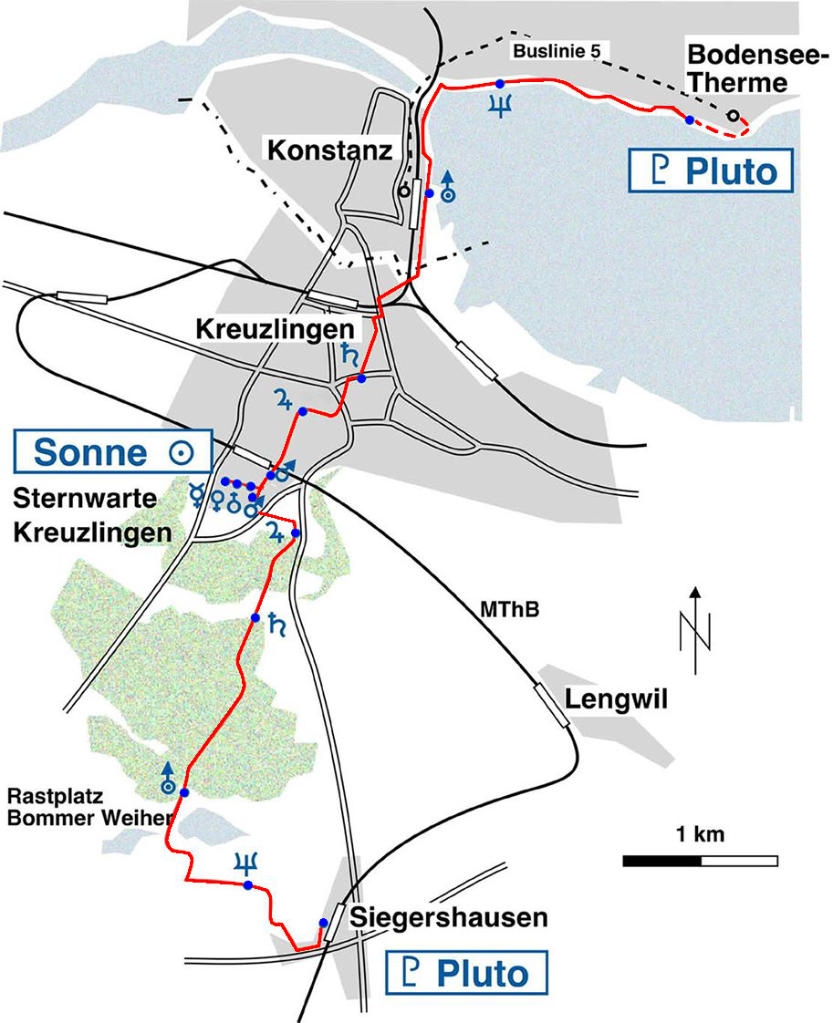

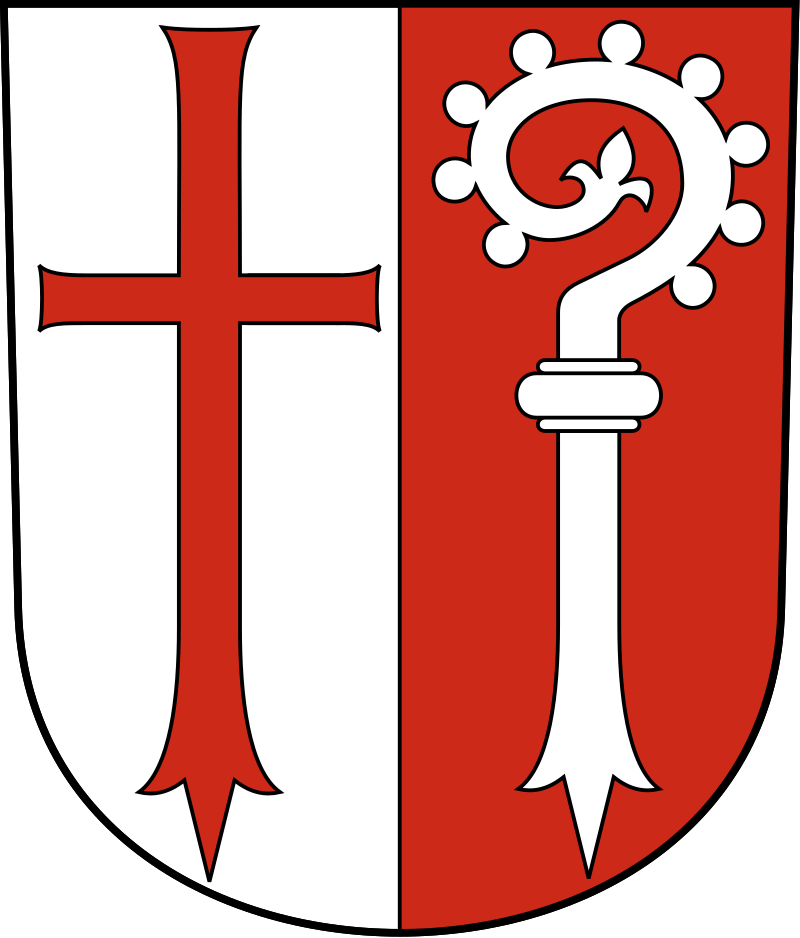

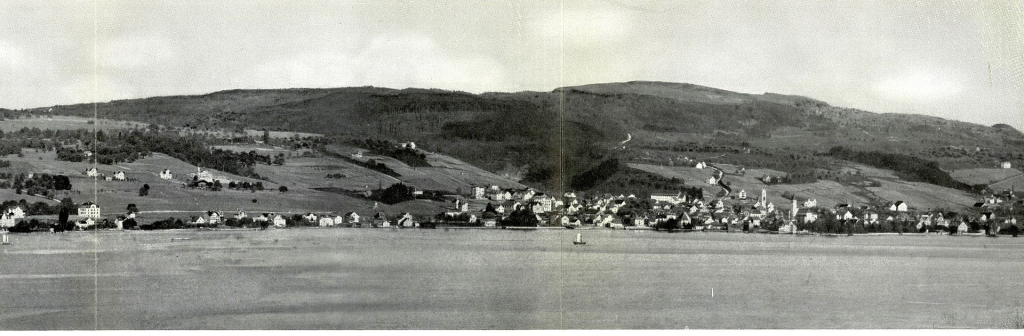

Kreuzlingen is a municipality in the canton of Thurgau in northeastern Switzerland.

It is the second-largest city of the canton (after Frauenfeld, the cantonal capital) with a population of about 22,000.

Together with the adjoining city of Konstanz (Constance) just across the border in Germany, Kreuzlingen is part of the largest conurbation on the Bodensee (Lake Constance) with a population of almost 120,000.

And it is Kreuzlingen’s location that is both its attraction and detraction.

One never goes to Kreuzlingen.

One goes through Kreuzlingen.

Unless one has no other choice but to linger.

When I lived in Landschlacht, 15 km to the east, I would go through Kreuzlingen en route to Konstanz or Zürich.

Only sheer bloody necessity would compel me to go to Kreuzlingen.

I would come to Kreuzlingen to go to the gym, for a husband must remain silent about the changes in a spouse’s body as she ages, but a wife is forever vocal about her dissatisfaction to aging in her husband’s form.

I treat gyms as I do banks or government institutions.

I go through the motions but I never enjoy myself when I do.

I would come to Kreuzlingen when between jobs I sought money from social services.

Time expended was never the same as money extended.

The rudeness and aggravation associated with these monthly endurance trials darkened my foul feelings towards Kreuzlingen even further.

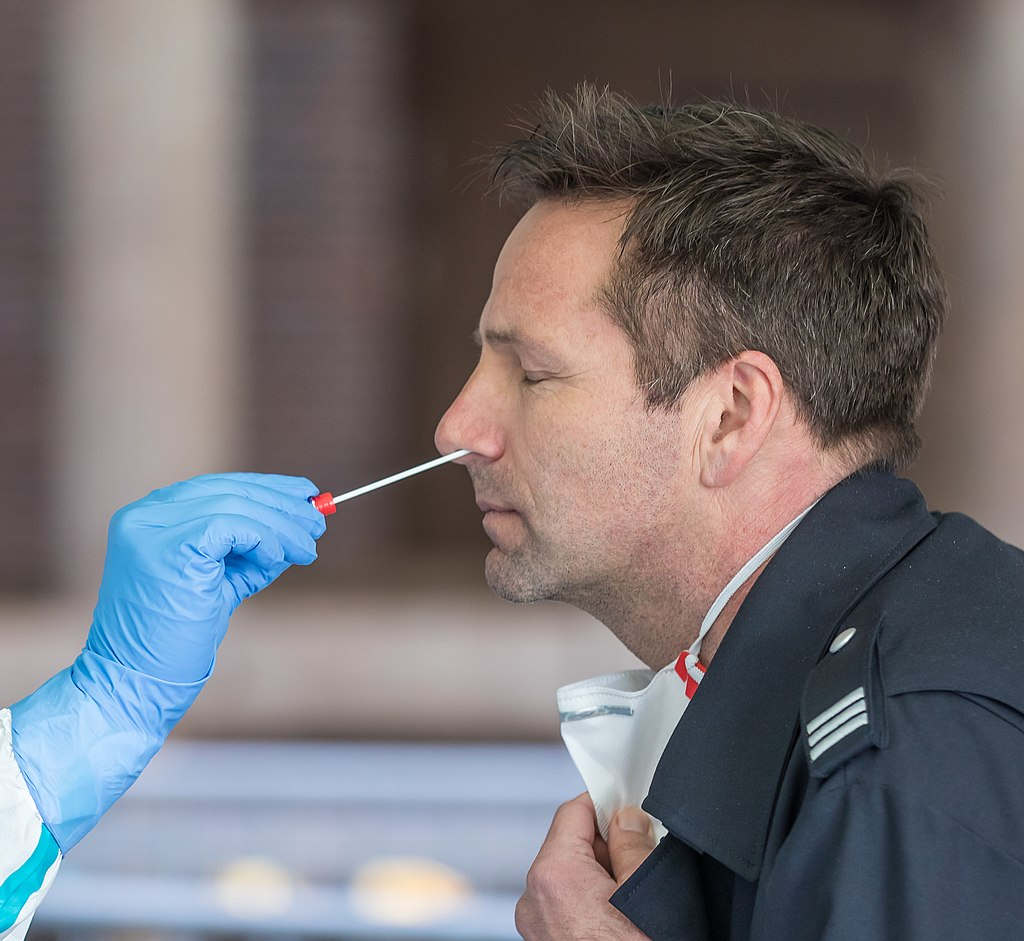

Kreuzlingen came to be further associated with unpleasantness, for it was the closest urban centre where residents of Landschlacht could get PCR testing for the coronavirus without a hospital visit.

Folks coming into the country from abroad, such as I from Turkey, had to be PCR tested within days of their arrival on Swiss soil, regardless of whether you had been tested before you left the land you had been in.

There is the old joke about what is European heaven and what is European hell:

Heaven is where:

- the police are British

- the chefs Italian

- the mechanics German

- the lovers French

- and everything is organized by the Swiss.

Hell is where:

- the police are German

- the chefs British

- the mechanics French

- the lovers Swiss

- and everything is organized by the Italians.

But I don’t think a Heaven where everything is organized by the Swiss is such a divine idea, especially when the ideas of enforcement (i.e. law and order) in German-speaking Schweiz are Germanic in attitude and application.

Add to this the universal axiom that governments everywhere love to take but loathe to give.

I, in some fit of madness, married a law-abiding German woman with whom I had moved to Switzerland.

She, in another type of insanity, married a cantankerous Canadian for whom rules rub him roughly.

Truly, opposites attract.

So, like husbands who capitulate to their wives’ whims for the sake of peace (never found) at home, I found myself submitting, yet again, to children in medical attire thrusting a sharp pointy object up a nasal cavity until the deposited brain matter is collected and assessed for that ever fateful announcement that you too might have contracted the coronavirus.

(And Chandler Bing, of Friends fame, sarcastically remarks:

“You need to stop the Q-tip when there’s resistance.“)

If I have one failing (among many) in my character, it is that I always try to find something positive about everyone and every situation.

My first impressions of Kreuzlingen were negative and I have tried, truly tried, to find something, anything, positive to change my attitude towards the place.

Even now, as I grumble about it, this post is trying, still, to give a fair and balanced view of a place I find it difficult to like.

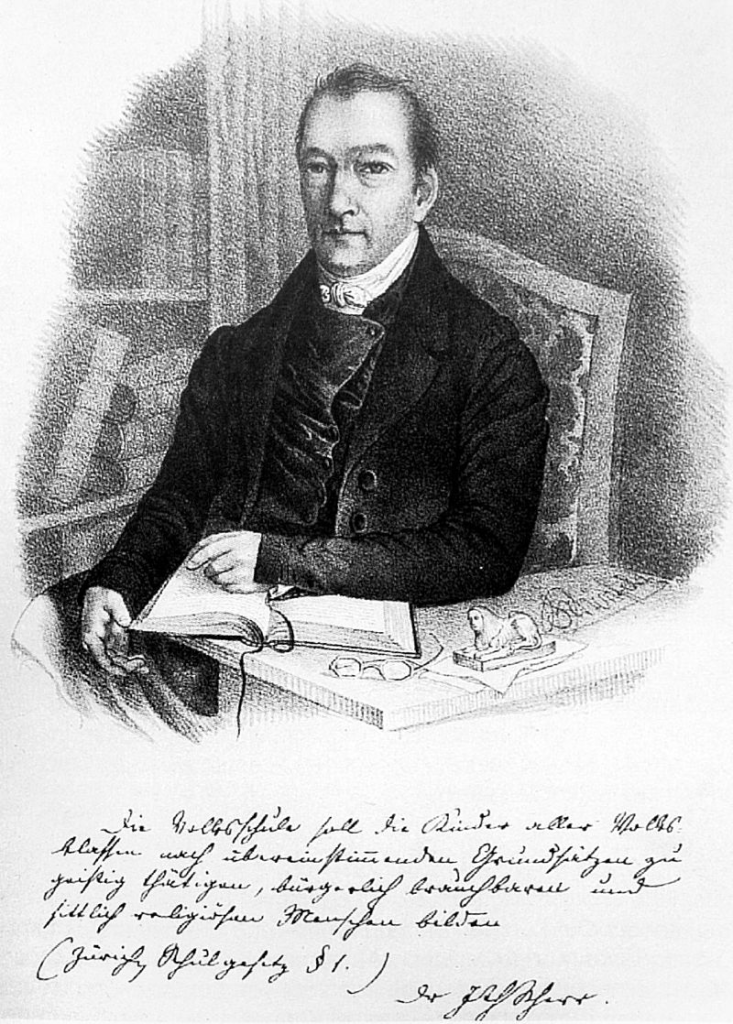

Consider its history and you may begin to see reasons for my ever present attitude.

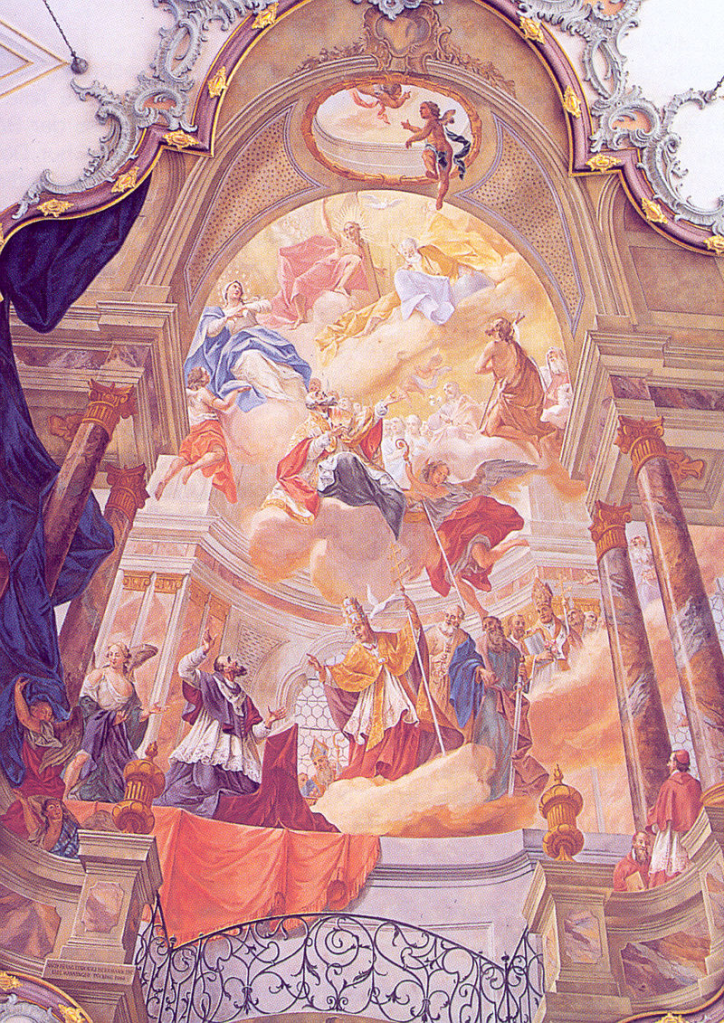

Konrad, Bishop of Konstanz (935 – 976) brought back from Jerusalem a fragment of the True Cross, which he presented to the hospital he had founded in the Konstanz suburb of Stadelhofen and from which it took the name of “Crucelin” which later became Crucelingen / Kreuzlingen.

The name of the municipality stems from the Augustinian monastery Crucelin, later Kreuzlingen Abbey.

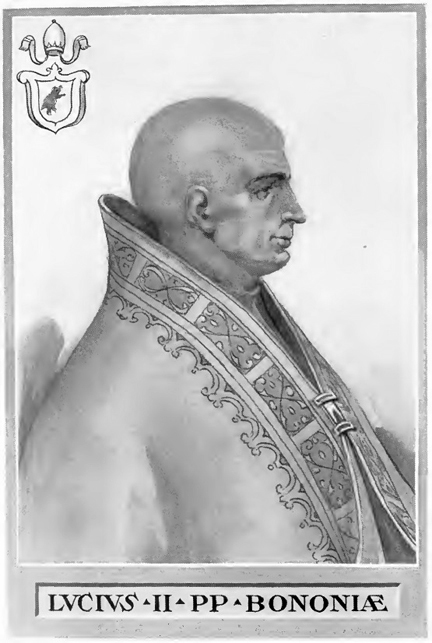

It was founded in 1125 by the Bishop of Constance (Konstanz) Ulrich I.

In 1144 Pope Lucius II, and in 1145 Emperor Frederick Barbarossa took the monastery under their protection.

The first monastery stood outside the city walls.

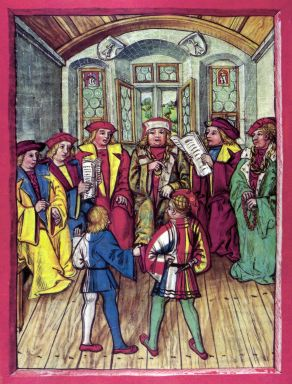

At the time of the Council of Constance (Konstanz) (1414 – 1418) the Abbot of Kreuzlingen gave shelter from 27 to 28 October 1414 to the later deposed Pope John XXIII.

Baldassarre Cossa (1370 – 1419) was Pisan Antipope John XXIII (1410 – 1415) during the Western Schism (a split within the Catholic Church, lasting from 1378 to 1417, in which bishops residing in Rome and Avignon both claimed to be the true Pope, and were joined by a third line of claimants from Pisa in 1409.).

The Catholic Church regards Cossa as an Antipope, as he opposed Pope Gregory XII whom the Catholic Church now recognizes as the rightful successor of Saint Peter.

Cossa was also an opponent of Antipope Benedict XIII, who was recognized by the French bishop as legitimate Pontiff.

Cossa was born in the Kingdom of Naples.

He participated in the Council of Pisa in 1408, which sought to end the Western Schism with the election of a third alternative Pope.

In 1410, Cossa succeeded Antipope Alexander V, taking the name John XXIII.

At the instigation of Sigismund, King of the Romans, Pope John called the Council of Constance of 1413, which deposed John XXIII and Benedict XIII, accepted Gregory XII’s resignation, and elected Pope Martin V to replace them, thus ending the Schism.

John XXIII was tried for various crimes, though later accounts question the veracity of those accusations.

Towards the end of his life Cossa restored his relationship with the Church and was made Cardinal Bishop of Frascati by Pope Martin V.

When asked by Emperor Frederick to also join the Swabian League, the Eidgenossen (Switzerland) flatly refused:

They saw no reason to join an alliance designed to further Habsburg interests, and they were wary of this new, relatively closely knit and powerful alliance that had arisen on their northern frontier.

Furthermore, they resented the strong aristocratic element in the Swabian League, so different from their own organization, which had grown over the last 200 years liberating themselves from precisely such an aristocratic rule.

On the Swabian (southern Germany, present day Württemberg) side, similar concerns existed.

For the common people in Swabia, the independence and freedom of the Eidgenossen was a powerful and attractive role model.

Many a baron in southern Swabia feared that his own subjects might revolt and seek adherence to the Swiss Confederacy.

These fears were not entirely without foundation:

The Swiss had begun to form alliances north of the Rhine River, concluding a first treaty with Schaffhausen in 1454 and then also treaties with cities as far away as Rottweil (Germany)(1463) and Mulhouse (France)(1466).

The city of Konstanz and its Bishop were caught in the middle between these two blocks:

They held possessions in Swabia, but the city also still exercised the high justice over Thurgau, where the Swiss had assumed the low justice since its annexation in 1460.

The foundation of the Swabian League prompted the Swiss city states of Zürich and Bern to propose accepting Konstanz into the Swiss Confederacy.

The negotiations failed, though, due to the opposition of the founding cantons of the Confederacy and Canton Uri in particular.

The split jurisdiction over Thurgau was the cause of many quarrels between the city and the Confederacy.

In 1495, one such disagreement was answered by a punitive expedition of soldiers of Uri.

Konstanz had to pay the sum of 3,000 guilders to make them retreat and cease their plundering.

(Thurgau was a territory of the Swiss Confederacy, and Uri was one of the cantons involved in its administration.)

Konstanz joined the Swabian League as a full member on 3 November 1498.

Although this did not yet definitively define the position of the city — during the Reformation, it would be allied again with Zürich and Bern, and only after the defeat of the Schmalkaldic League in 1548 its close connections to the Eidgenossenschaft would be finally severed — it was another factor contributing to the growing estrangement between the Swiss and the Swabians.

The Schmalkaldic League was a military alliance of Lutheran princes within the Holy Roman Empire during the mid-16th century.

Although created for religious motives soon after the start of the Reformation, its members later came to have the intention that the League would replace the Holy Roman Empire as their focus of political allegiance.

While it was not the first alliance of its kind, unlike previous formations, the Schmalkaldic League had a substantial military to defend its political and religious interests.

It received its name from the town of Schmalkalden, Thuringia, Germany.

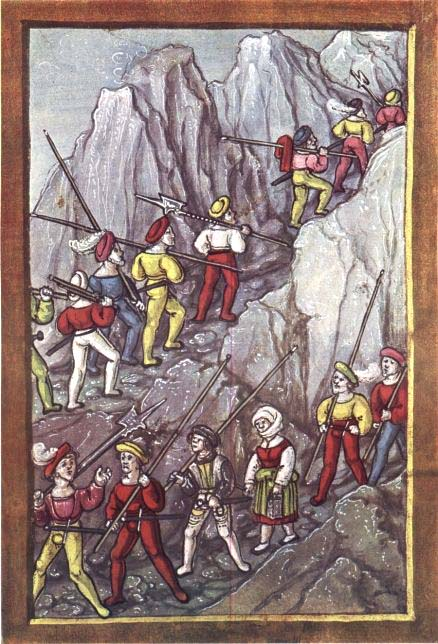

The competition between Swiss (Reisläufer) and Swabian (Landsknechte) mercenaries, who both fought in armies throughout Europe, sometimes opposing each other on the battlefield, sometimes competing for contracts, intensified.

Contemporary chronicles agree in their reports that the Swiss, who were considered the best soldiers in Europe at the time after their victories in the Burgundian Wars (1474 – 1477), were subject to many taunts and abuses by the Landsknechte.

They were called “Kuhschweizer“ (Swiss cow herders) and ridiculed in other ways.

Such insults were neither given nor taken lightly, and frequently led to bloodshed.

Indeed, such incidents would contribute to prolong the Swabian War itself by triggering skirmishes and looting expeditions that the military commands of neither side had ever wanted or planned.

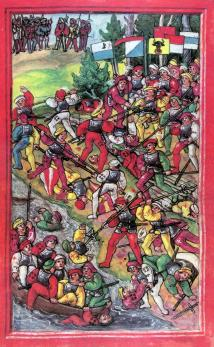

A large attack of the Swabian League took place on 11 April 1499:

Swabian troops occupied and plundered some villages on the southern shore of the Bodensee, just south of Konstanz.

The expedition ended in a shameful defeat and open flight when the Swiss soldiers, who had their main camp just a few miles south at Schwaderloh, arrived and met the Swabians in the Battle of Schwaderloh.

The Swabians lost more than 1,000 soldiers – 130 from the city of Konstanz alone.

The Swiss captured their heavy equipment, including their artillery.

The continued defeats of both Habsburg and Swabian armies made King Maximilian, who had hitherto been occupied in the Netherlands, travel to Konstanz and assume the leadership of the operations himself.

He declared an imperial ban over the Swiss Confederacy in an attempt to gain wider support for the operation amongst the German princes by declaring the conflict an “imperial war“.

However, this move had no success.

The refusal of the military leaders of the Swabian League to withdraw troops from the northern front to send them to the Grisons as Maximilian had demanded made the King return to the Bodensee.

The differences between the Swabians, who preferred to strike in the north, and the King, who still hoped to convince them to help him win the struggle in the Val Müstair, led to a pause in the hostilities.

Troops were assembled at Konstanz, but an attack did not occur.

Until July, nothing of significance happened along the whole front.

By mid-July, Maximilian and the Swabian leaders suddenly were under pressure from their own troops.

In the west, where there lay an army under the command of Count Heinrich von Fürstenberg, a large contingent of mercenaries from Flanders and many knights threatened to leave as they had not received their pay.

The foot soldiers of the Swabian troops also complained:

Most of them were peasants and preferred to go home and bring in the harvest.

Maximilian was forced to act.

An attack by sea across the Bodensee on Rheineck and Rorschach on 21 July 1499 was one of the few successful Swabian operations.

The small Swiss detachment was taken by surprise, the villages plundered and burnt.

A much larger attack of an army of about 16,000 soldiers in the west on Dornach, however, met a quickly assembled but strong Swiss army.

In the Battle of Dornach on 22 July 1499, the Swabian and mercenary troops suffered a heavy defeat after a long and hard battle.

Their general Heinrich von Fürstenberg fell early in the fight, about 3,000 Swabian and 500 Swiss soldiers died, and the Swabians lost all of their artillery.

Again.

A major problem for the Swiss was the lack of any unified command.

The cantonal contingents only took orders from their own leaders.

Complaints of insubordination were common.

The Swiss Diet had to adopt this resolution on 11 March 1499:

“Every canton shall impress upon its soldiers that when the Confederates are under arms together, each one of them, whatever his canton, shall obey the officers of the others.“

The Swabian and Habsburg armies had suffered far higher human losses than the Swiss, and were also short on artillery, after repeatedly having lost their equipment to the Swiss.

The Swiss also had no desire to prolong the war further.

Finally, Maximilian and the Swiss signed the Peace of Basel on 22 September 1499.

After the Swabian War (1499), in the Peace of Basel, the Duke of Milan ceded the sovereignty of Thurgau to the Swiss.

This so angered the inhabitants of Konstanz that they burned down the Abbey of Kreuzlingen.

The city was compelled to rebuild the Abbey.

On 17 April 1509, Abbot Peter I von Babenberg (1498 – 1545) was able to rededicate the new church.

During the Thirty Years’ War (1618 – 1648), despite the neutrality of the Swiss, a Swedish army entered Thurgau via Stein am Rhein, advanced on Kreuzlingen and besieged Konstanz unsuccessfully, losing several thousand men.

When on 2 October 1633, the troops left Kreuzlingen, the people of Konstanz blamed the monks for having supported the enemy and destroyed the Abbey a second time.

It was now decided that the monastery should not be rebuilt right up against the walls of Konstanz, but should be removed from it by not less than the distance of a cannon shot.

During the Protestant Reformation (1516 – 1648) in Switzerland, both the Catholic and emerging Reformed parties sought to swing the subject territories, such as Canton Thurgau, to their side.

In 1524, in an incident that resonated across Switzerland, local peasants occupied the Cloister of Ittingen in Thurgau, driving out the monks, destroying documents, and devastating the wine cellar.

Between 1526 and 1531, most of Thurgau’s population adopted the new Reformed faith spreading from Zürich.

Zürich’s defeat in the War of Kappel (1531) ended Reformed predominance.

Instead, the First Peace of Kappel protected both Catholic and Reformed worship, though the provisions of the treaty generally favored the Catholics, who also made up a majority among the seven ruling cantons.

Religious tensions over Thurgau were an important background to the First War of Villmergen (1656), during which Zürich briefly occupied Thurgau.

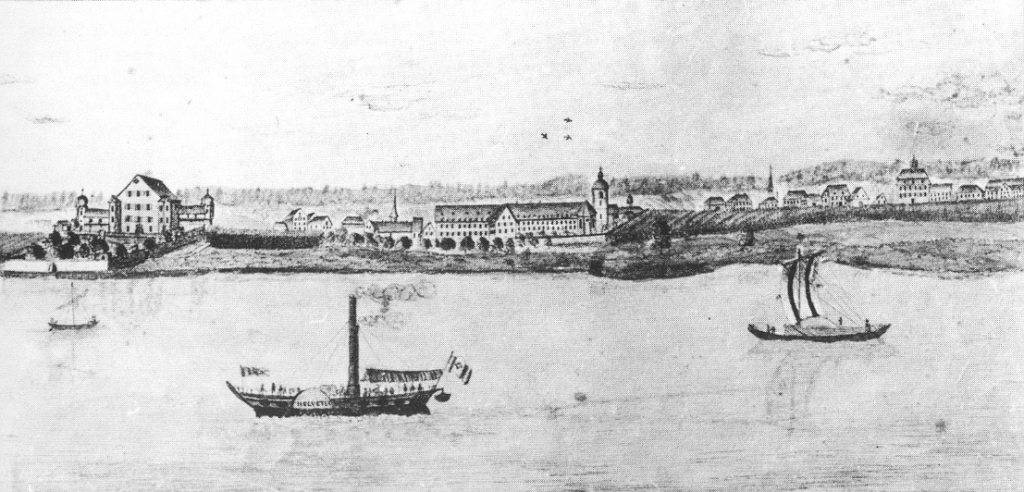

At the beginning of the 19th century, today’s centre of Kreuzlingen was largely arable land, meadowland and vineyards.

Around the monastery stood 13 houses.

With the reorganization of Europe, Kreuzlingen became a border region.

The first customs house was built in 1818.

The first steamboats that operated on the Bodensee from 1824 and the construction of the railway lines to Romanshorn (1871) and Etzwilen (1875) attracted trade and industry.

Until the First World War (1914 – 1918) Kreuzlingen was a kind of suburb of Konstanz.

Industry in Kreuzlingen was also almost exclusively in the hands of German entrepreneurs.

It was only after the border was closed during the War that Kreuzlingen became more independent.

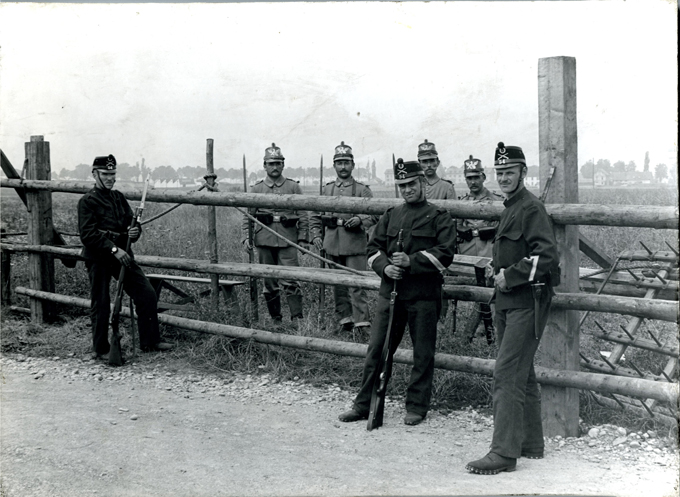

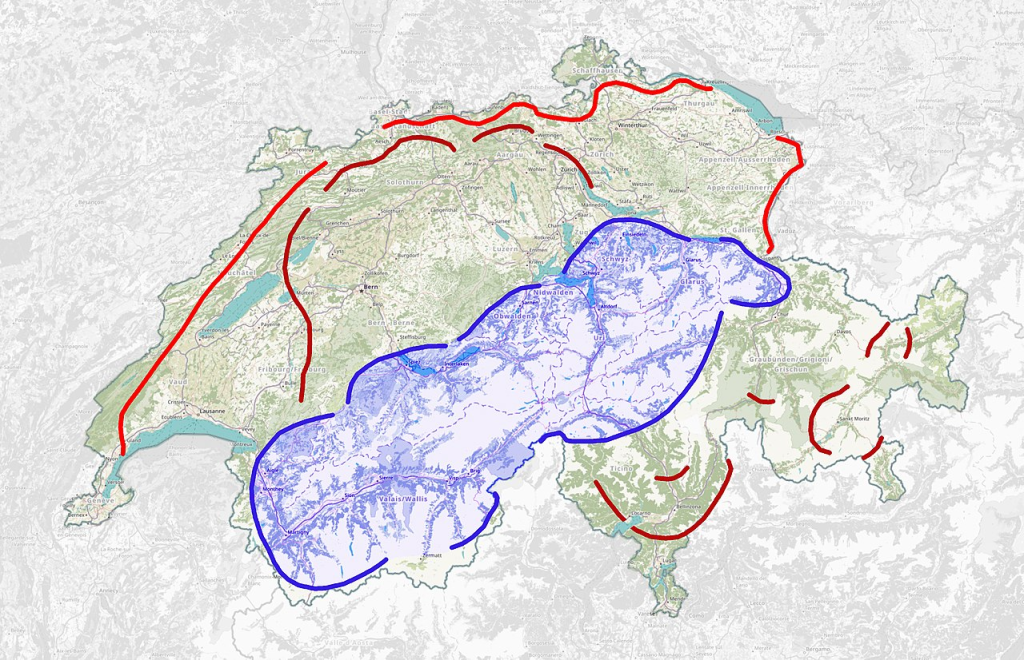

During World War I (1914 – 1918) and World War II (1939 – 1945) Switzerland maintained armed neutrality, and was not invaded by its neighbors, in part because of its topography, much of which is mountainous.

Consequently, it was of considerable interest to belligerent states as the scene for diplomacy, espionage, and commerce, as well as being a safe haven for refugees.

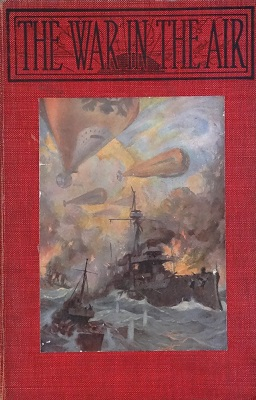

In The War in the Air – an apocalyptic prediction of the coming global conflict, published in 1903, eleven years before the actual outbreak of war – H.G. Wells assumed that Switzerland would join the coming war and fight on the side of Germany.

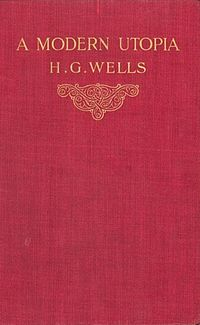

Wells is known to have visited Switzerland in 1903, a visit which inspired his book A Modern Utopia, and his assessment of Swiss inclinations might have been inspired by what he heard from Swiss people in that visit.

Switzerland maintained a state of armed neutrality during the First World War.

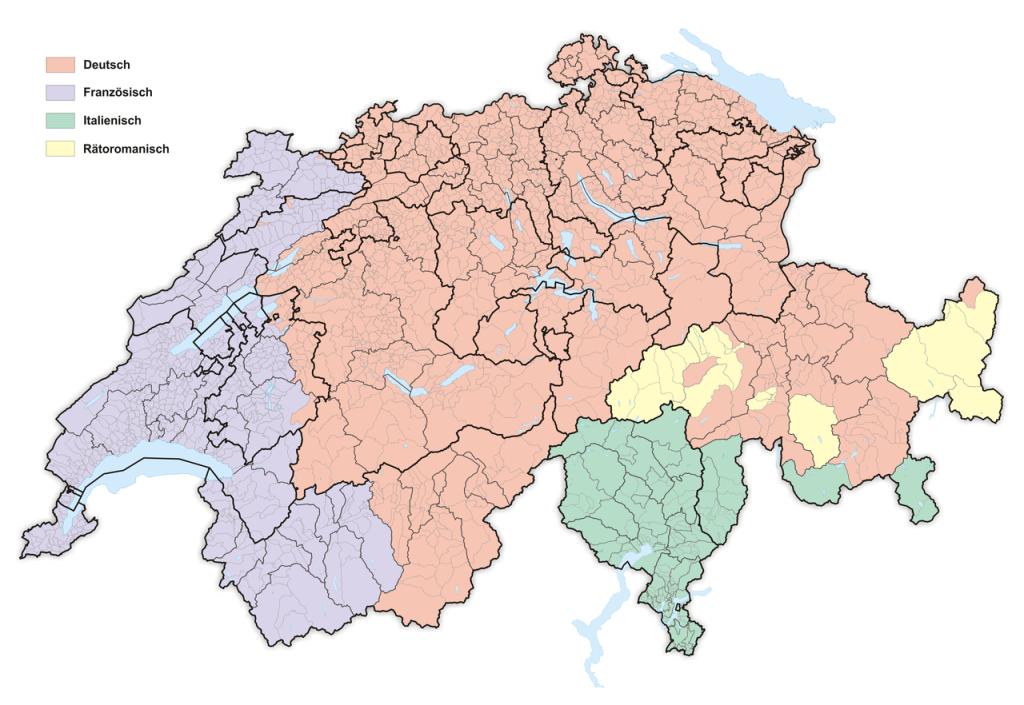

However, with two of the Central Powers (Germany and Austria-Hungary) and two of the Entente Powers (France and Italy) all sharing borders and populations with Switzerland, neutrality proved difficult.

Under the Schlieffen Plan, the German General Staff had been open to the possibility of trying to outflank the French fortifications by marching through Switzerland in violation of its neutrality, although the plan’s eventual executor Helmuth von Moltke the Younger selected Belgium instead due to Switzerland’s mountainous topography and the disorganized state of the Belgian Armed Forces.

From December 1914 until the spring of 1918, Swiss troops were deployed in the Jura along the French border over concern that the trench war might spill into Switzerland.

Of lesser concern was the Italian border, but troops were also stationed in the Unterengadin region of Graubünden.

While the German-speaking majority in Switzerland generally favored the Central Powers, the French- and, later, Italian-speaking populations sided with the Entente Powers, which would cause internal conflict in 1918.

However, the country managed to keep out of the War, although it was blockaded by the Allies and therefore suffered some difficulties.

Nevertheless, because Switzerland was centrally located, neutral, and generally undamaged, the War allowed the growth of the Swiss banking industry.

For the same reasons, Switzerland became a haven for foreign refugees and revolutionaries.

There were a number of Swiss neutrality scandals during the war, when certain people within Switzerland were found to have been favouring one side or the other.

One of the worst was the “two colonels” affair.

In February 1916, two senior Swiss intelligence officers were found to have been passing copies of intelligence reports and other sensitive material to the German and Austrian military attaches in Switzerland for nearly a year.

This included signals sent between foreign embassies in Switzerland and their home governments, which the Swiss had intercepted.

The two officers defended themselves by saying that no secret information had been given away, and that information had been received from the Central Powers in return.

Although they were sacked, they received no other punishment.

Being neutral, Switzerland was also a place where exiles could go.

Czech and Lithuanian national councils were established in Switzerland during the War.

In 1914, both these countries were part of a larger empire (Austria-Hungary and Russia respectively) and these national councils sought independence.

King Constantine of Greece went into exile in Switzerland in June 1917.

After the Great War, the Austrian Imperial family fled to Switzerland.

Following the organization of the army in 1907 and military expansion in 1911, the Swiss Army consisted of about 250,000 men with an additional 200,000 in supporting roles.

Both European alliance-systems took the size of the Swiss military into account in the years prior to 1914, especially in the Schlieffen Plan.

Following the declarations of war in late July 1914, on 1 August 1914, Switzerland mobilized its army.

By 7 August the newly appointed general Ulrich Wille had about 220,000 men under his command.

By 11 August Wille had deployed much of the army along the Jura border with France, with smaller units deployed along the eastern and southern borders.

This remained unchanged until May 1915 when Italy entered the war on the Entente side, at which point troops were deployed to the Unterengadin valley, Val Müstair and along the southern border.

Once it became clear that the Allies and the Central Powers would respect Swiss neutrality, the number of troops deployed began to drop.

After September 1914, some soldiers were released to return to their farms and to vital industries.

By November 1916 the Swiss had only 38,000 men in the army.

This number increased during the winter of 1916 – 1917 to over 100,000 as a result of a proposed French attack that would have crossed Switzerland.

When this attack failed to occur the army began to shrink again.

Because of widespread workers’ strikes, at the end of the War the Swiss army had shrunk to only 12,500 men.

During the War “belligerents” crossed the Swiss borders about 1,000 times, with some of these incidents occurring around the Dreisprachen Piz (Three Languages Peak), near the Stevio Pass.

Switzerland had an outpost and a hotel (which was destroyed as it was used by the Austrians) on the peak.

During the War, fierce battles were fought in the ice and snow of the area, with gunfire coming on to Swiss territory.

The three nations made an agreement not to fire over Swiss territory, which jutted out between Austria (to the north) and Italy (to the south).

Instead they could fire down the pass, as Swiss territory was around the peak.

In one incident, a Swiss soldier was killed at his outpost on Dreisprachen Piz by Italian gunfire.

During the fighting, Switzerland became a haven for many politicians, artists, pacifists, and thinkers.

Bern, Zürich and Geneva became centres of debate and discussion.

In Zürich, two very different anti-war groups, the Bolsheviks and the Dadaists, would bring lasting changes to the world.

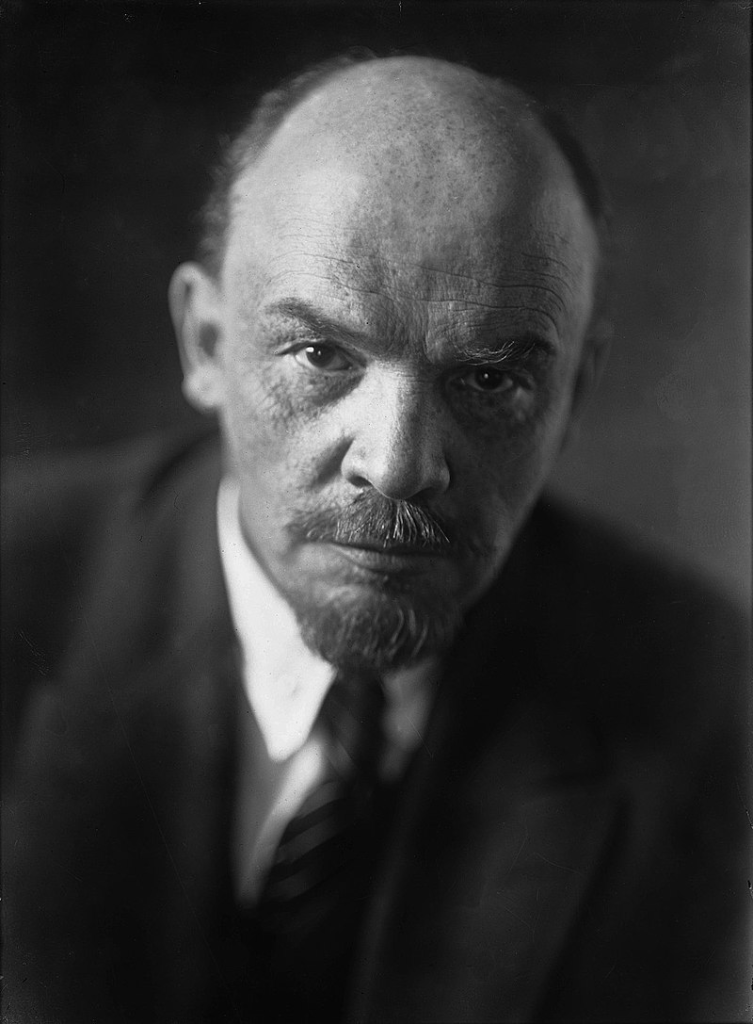

The Bolsheviks were a faction of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party, centered around Vladimir Lenin.

Following the outbreak of the War, Lenin was stunned when the large Social Democratic parties of Europe (at that time predominantly Marxist in orientation) supported their various respective countries’ war efforts.

Lenin, believing that the peasants and workers of the proletariat were fighting for their class enemies, adopted the stance that what he described as an “imperialist war” ought to be turned into a civil war between the classes.

He left Austria for neutral Switzerland in 1914 following the outbreak of the War and remained active in Switzerland until 1917.

Following the 1917 February Revolution in Russia and the abdication of Tsar Nicholas II, he left Switzerland on a sealed train to Petrograd, where he would shortly lead the 1917 October Revolution in Russia.

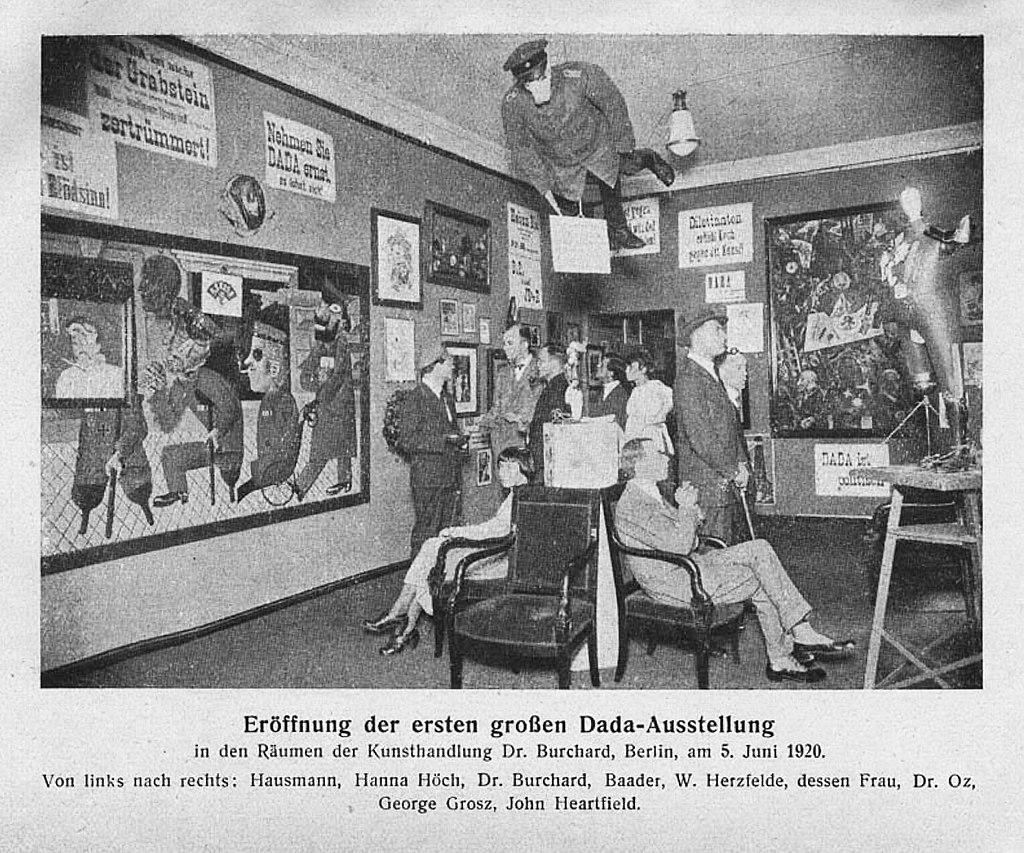

While the Dada art movement was also an anti-war organization, Dadaists used art to oppose all wars.

The founders of the movement had left Germany and Romania to escape the destruction of the War.

At the Cabaret Voltaire in Zürich they put on performances expressing their disgust with the War and with the interests that inspired it.

By some accounts Dada coalesced on 6 October 1916 at the Cabaret.

The artists used abstraction to fight against the social, political, and cultural ideas of that time that they believed had caused the War.

Dadaists viewed abstraction as the result of a lack of planning and of logical thought-processes.

When World War I ended in 1918, most of the Zürich Dadaists returned to their home countries, and some began Dada activities in other cities.

In 1917, Switzerland’s neutrality came into question when the Grimm – Hoffmann Affair erupted.

Robert Grimm, a Swiss socialist politician, travelled to Russia as an activist to negotiate a separate peace between Russia and Germany, in order to end the war on the Eastern Front in the interests of socialism and pacifism.

Misrepresenting himself as a diplomat and an actual representative of the Swiss government, he made progress but had to admit to fraud and return home when the Allies found out about the proposed peace deal.

The Allies were placated by the resignation of Arthur Hoffmann, the Swiss Federal Councillor who had supported Grimm but had not consulted his colleagues on the initiative.

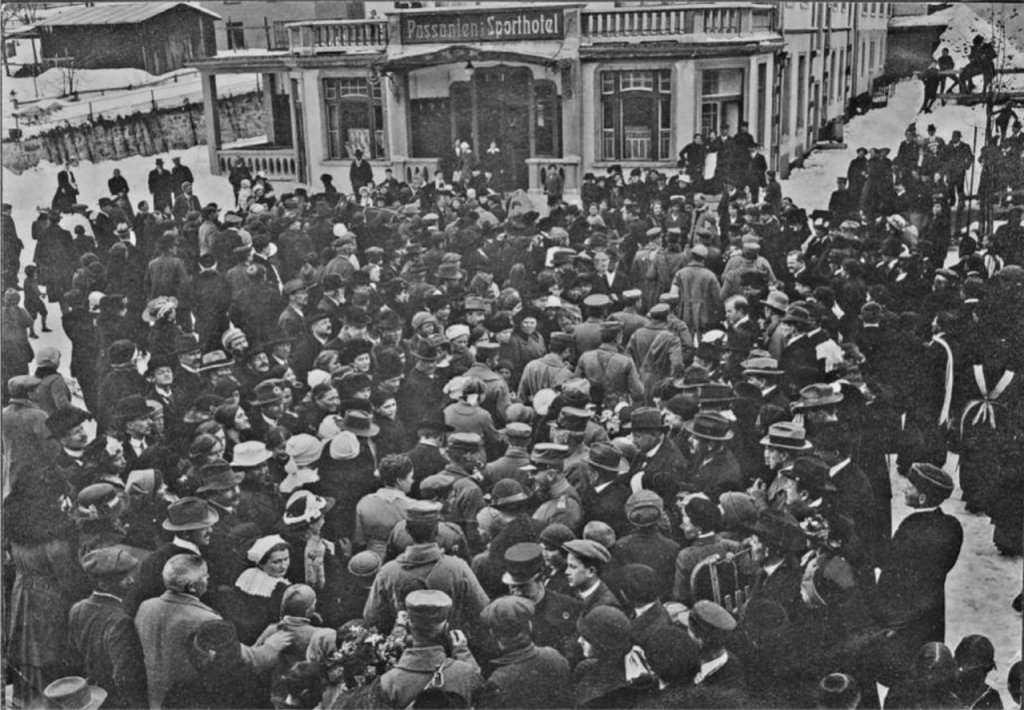

During the War, Switzerland accepted 68,000 British, French and German wounded prisoners of war (POWs) for recovery in mountain resorts.

To be transferred the wounded had to have a disability that would negate their further military service or have been interned over 18 months with deteriorating mental health.

The wounded were transferred from POW camps unable to cope with the number of wounded and sat out the war in Switzerland.

The transfer was agreed between the warring powers and organised by the Red Cross.

In 1934, the Swiss Banking Act was passed.

The law was announced in front of the Three Confederates statue to the Swiss public and international community in the Federal Palace of Switzerland during a 1934 special assembly.

This allowed for anonymous numbered bank accounts, in part to allow Germans (including Jews) to hide or protect their assets from seizure by the newly established Third Reich.

In 1936, Wilhelm Gustloff was assassinated at Davos.

He was the head of the Nazi Party’s “Auslands-Organisation” in Switzerland.

The Swiss government refused to extradite the alleged assassin David Frankfurter to Germany.

Frankfurter was sentenced to 18 years in prison but was pardoned in 1946.

As European tension grew in the 1930s, the Swiss began to rethink their political and military situation.

The Social Democratic Party abandoned their revolutionary and anti-military stances, and soon the country began to rearm for war.

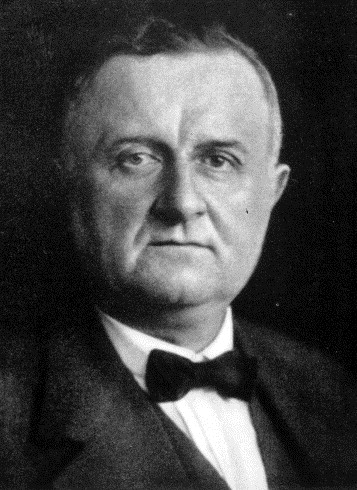

Farmers, Traders and Citizens’ Party (BGB) Federal Councillor Rudolf Minger, predicting war would come in 1939, led the rebuilding of the Swiss Army.

Starting in 1936, he secured a larger defence budget and started a war bond system.

The army was restructured into smaller, better equipped divisions and boot camps for conscripts was extended to three months of instruction.

In 1937, a war economy cell was established.

Households were encouraged to keep a two-month supply of food and basic necessities.

In 1938, Foreign Minister Giuseppe Motta withdrew Switzerland from the League of Nations, returning the country to its traditional form of neutrality.

Actions were also taken to prove Switzerland’s independent national identity and unique culture from the surrounding Fascist powers.

This policy was known as Geistige Landesverteidigung (spiritual national defence).

In 1937, the government opened the Museum of Federal Charters.

Increased use of Swiss German coincided with a national referendum that made Romansh a national language in 1938, a move designed to counter Benito Mussolini’s attempts to incite Italian nationalism in the southern Grisons and Ticino cantons.

In December of that year in a government address, Catholic Conservative Councillor Philipp Etter urged a defence of Swiss culture.

Geistige Landesverteidigung subsequently exploded, being featured on stamps, in children’s books, and through official publications.

At the outbreak of World War II in 1939, Switzerland immediately began to mobilize for a possible invasion.

The transition into wartime was smooth and caused less controversy than in 1914.

The country was fully mobilized in only three days.

Parliament quickly selected the 61-year-old career soldier Henri Guisan to be General.

By 3 September, 430,000 combat troops and 210,000 in support services, 10,000 of whom were women, had been mobilized, though most of these were sent home during the Phoney War.

At its highest point, 850,000 soldiers were mobilized.

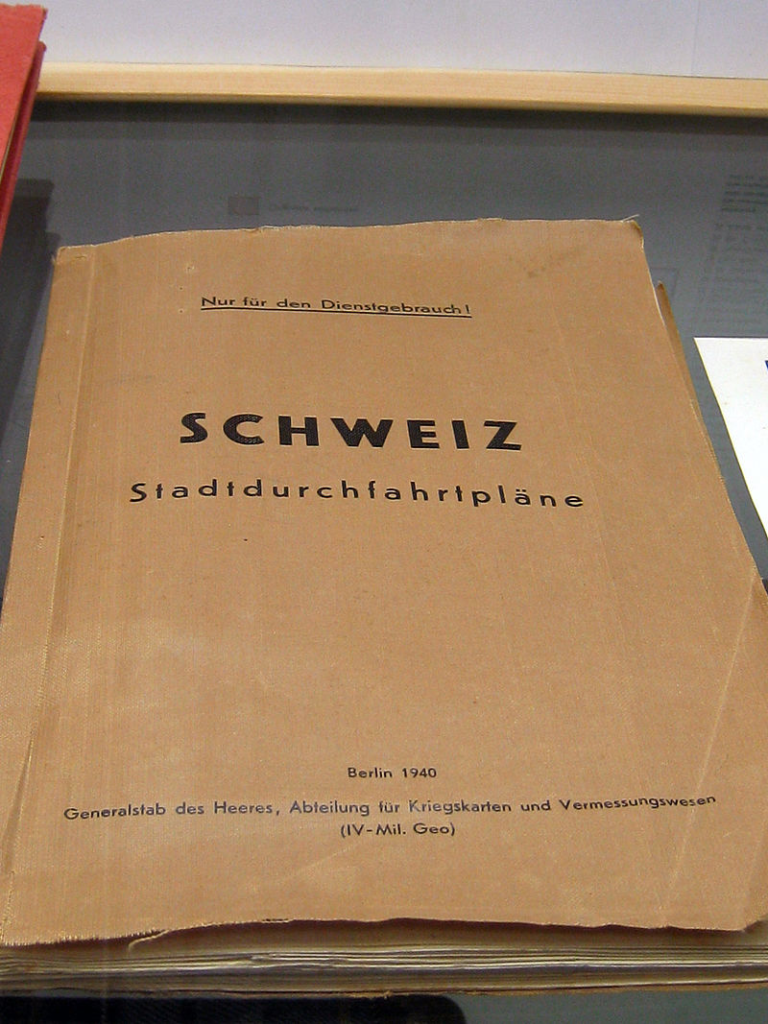

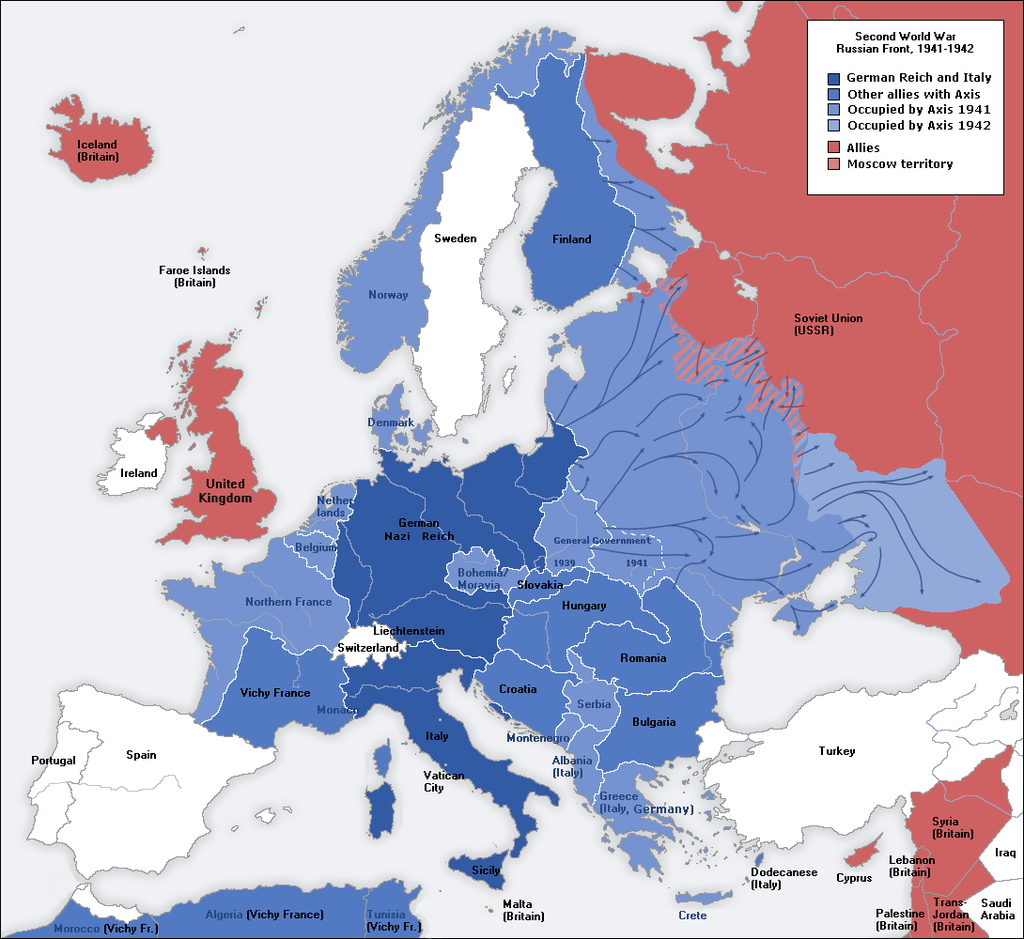

During the War, under the pan-Germanist and antidemocratic Neuordnung (New Order) doctrine, detailed invasion plans were drawn up by the German military command, such as Operation Tannenbaum (Christmas tree), but Switzerland was never attacked.

Switzerland was able to remain independent through a combination of military deterrence, economic concessions to Germany and good fortune as larger events during the War delayed an invasion.

The New Order (Neuordnung) of Europe was the political order which Nazi Germany wanted to impose on the conquered areas under its dominion.

The establishment of the Neuordnung had already begun long before the start of World War II, but was publicly proclaimed by Adolf Hitler in 1941:

“The year 1941 will be, I am convinced, the historical year of a great European New Order!“

Among other things, it entailed the creation of a pan-German racial state, structured according to Nazi ideology, to ensure the existence of a perceived Aryan – Nordic master race, consolidate a massive territorial expansion into Central and Eastern Europe through colonization by German settlers, achieve the physical annihilation of Jews, Slavs, (especially Poles and Russians), Roma (“gypsies“), and others considered to be “unworthy of life“, as well as the extermination, expulsion or enslavement of most of the Slavic peoples and others regarded as “racially inferior“.

Nazi Germany’s desire for aggressive territorial expansionism was one of the most important causes of World War II.

Historians are still divided as to its ultimate goals, some believing that it was to be limited to Nazi German domination of Europe, while others maintain that it was a springboard for eventual world conquest and the establishment of a world government under German control.

The Führer gave expression to his unshakable conviction that the Reich will be the master of all Europe.

We shall yet have to engage in many fights, but these will undoubtedly lead to most wonderful victories.

From there on the way to world domination is practically certain.

Whoever dominates Europe will thereby assume the leadership of the world.

— Joseph Goebbels, Reich Minister of Propaganda, 8 May 1943

Attempts by the Swiss Nazi Party to effect a unification with Germany failed, largely as a result of Switzerland’s sense of national identity and tradition of democracy and civil liberties.

The Swiss press criticized the Third Reich, often infuriating its leadership.

In turn, Berlin denounced Switzerland as a medieval remnant and its people renegade Germans.

Swiss military strategy was changed from one of static defence at the borders to a strategy of attrition and withdrawal to strong, well-stockpiled positions high in the Alps known as the National Redoubt.

This controversial strategy was essentially one of deterrence.

The idea was to render the cost of invading too high.

During an invasion, the Swiss Army would cede control of the economic heartland and population centres but retain control of crucial rail links and passes in the National Redoubt.

Switzerland was a base for espionage by both sides in the conflict and often mediated communications between the Axis and Allied powers by serving as a protecting power.

In 1942, the United States Office of Strategic Services (OSS) was established in Bern.

Through the efforts of Allen Dulles, the first US intelligence service in Western Europe was created.

During the allied invasion of Italy, the OSS in Switzerland guided tactical efforts for the takeover of Salerno and the islands of Corsica and Sardinia.

Despite the public and political attitudes in Switzerland, some higher-ranking officers within the Swiss Army had pro-Nazi sympathies: notably Colonel Arthur Fonjallaz and Colonel Eugen Bircher, who led the Schweizerischer Vaterländischer Verband.

In Letters to Suzanne (French: Lettres à Suzanne, Lausanne, Switzerland, 1949), the Swiss journalist Léon Savary retrospectively denounced in this sense “the occult influence of Hitlerism on the Swiss people during the Second World War, which they were not conscious of being under“.

Nazi Germany repeatedly violated Swiss airspace.

During the Battle of France in 1940, German aircraft violated Swiss airspace at least 197 times.

In several air incidents, the Swiss shot down 11 Luftwaffe aircraft between 10 May and 17 June 1940, while suffering the loss of three of their own aircraft.

Germany protested diplomatically on 5 June and with a second note on 19 June which contained explicit threats.

Hitler was especially furious when he saw that German equipment was used to shoot down German pilots.

He said they would respond “in another manner“.

On 20 June, the Swiss air force was ordered to stop intercepting planes violating Swiss airspace.

Swiss fighters began instead to force intruding aircraft to land at Swiss airfields.

Anti-aircraft units still operated.

Later, Hitler and Hermann Göring sent saboteurs to destroy Swiss airfields, but they were captured by Swiss troops before they could cause any damage.

Skirmishes between German and Swiss troops took place on the northern border of Switzerland throughout the war.

Allied aircraft intruded on Swiss airspace throughout World War II.

In total, 6,304 Allied aircraft violated Swiss airspace during the war.

Some damaged Allied bombers returning from raids over Italy and Germany would intentionally violate Swiss airspace, preferring internment by the Swiss to becoming POWs.

Over a hundred Allied aircraft and their crews were interned in this manner.

They were subsequently put up in various ski resorts that had been emptied from lack of tourists due to the war and held until hostilities ended.

At least 940 American airmen attempted to escape into France after the Allied invasion of Normandy in June 1944 but Swiss authorities intercepted 183 internees.

Over 160 of these airmen were incarcerated in a Swiss prison camp known as Wauwilermoos, which was located near Lucerne (Luzern) and commanded by André Béguin, a pro-Nazi Swiss officer.

The American internees remained in Wauwilermoos until November 1944 when the US State Department lodged protests against the Swiss government and eventually secured their release.

The American military attaché in Bern warned Marcel Pilet – Golaz, Swiss foreign minister in 1944, that “the mistreatment inflicted on US aviators could lead to ‘navigation errors’ during bombing raids over Germany“.

Switzerland, surrounded by Axis-controlled territory, also suffered from Allied bombings during the War – most notably from the accidental bombing of Schaffhausen by American aircraft on 1 April 1944.

“Destroyed by airmen 1 April 1944, rebuilt 1944/1945“

It was mistaken for Ludwigshafen am Rhein, a German town 284 kilometres (176 mi) away.

Forty people were killed and over fifty buildings destroyed, among them a group of small factories producing anti-aircraft shells, ball bearings and Bf 109 parts for Germany.

The bombing limited much of the leniency the Swiss had shown toward Allied airspace violations.

Eventually, the problem became so bad that they declared a zero-tolerance policy for violation by either Axis or Allied aircraft and authorized attacks on American aircraft.

Victims of these mistaken bombings were not limited to Swiss civilians, but included the often confused American aircrews, shot down by the Swiss fighters as well as several Swiss fighters shot down by American airmen.

In February 1945, 18 civilians were killed by Allied bombs dropped over Stein am Rhein, Vals and Rafz.

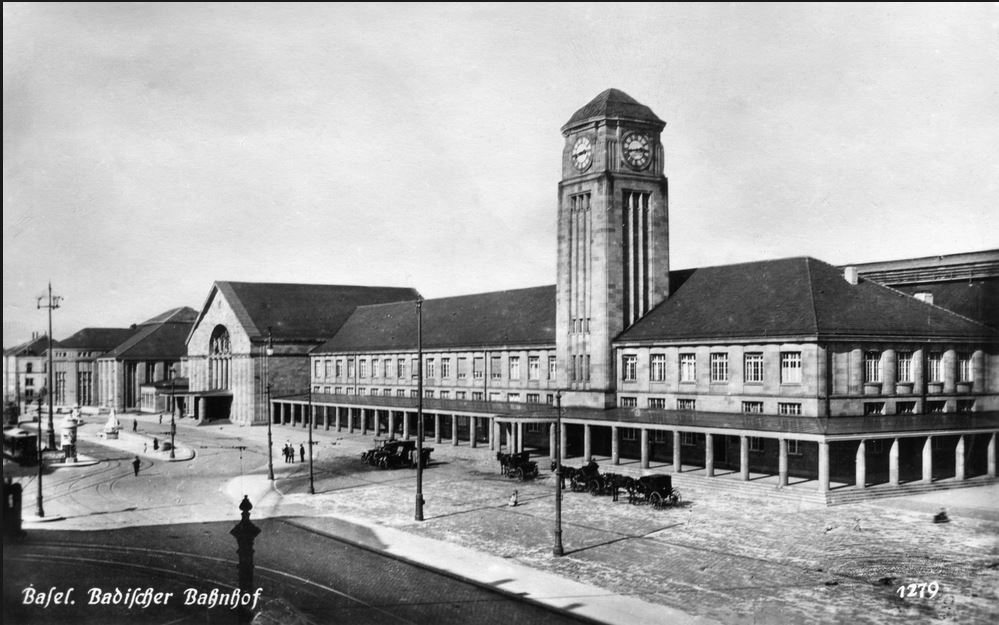

Arguably the most notorious incident came on 4 March 1945, when Basel and Zürich were accidentally bombed by American aircraft.

The attack on Basel’s railway station led to the destruction of a passenger train, but no casualties were reported.

A B-24 Liberator dropped its bomb load over Zürich, destroying two buildings and killing five civilians.

The crew believed that they were attacking Freiburg im Breisgau in Germany.

As John Helmreich points out, the pilot and navigator, in choosing a target of opportunity, “missed the marshalling yard they were aiming for, missed the city they were aiming for, and even missed the country they were aiming for“.

The Swiss, although somewhat skeptical, reacted by treating these violations of their neutrality as “accidents“.

The United States was warned that single aircraft would be forced down and their crews would still be allowed to seek refuge, while bomber formations in violation of airspace would be intercepted.

While American politicians and diplomats tried to minimize the political damage caused by these incidents, others took a more hostile view.

Some senior commanders argued that as Switzerland was “full of German sympathizers“, it deserved to be bombed.

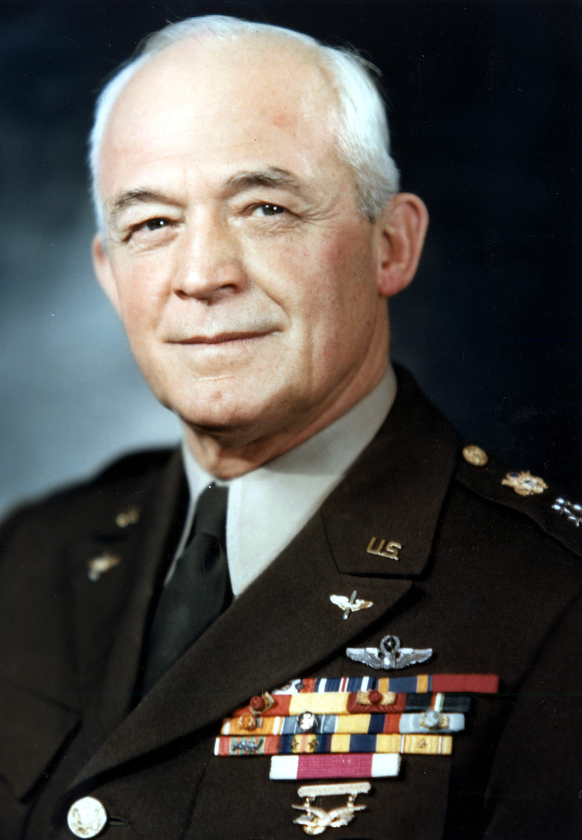

General Henry H. Arnold, Commanding General of the US Army Air Forces, even suggested that it was the Germans themselves who were flying captured Allied planes over Switzerland in an attempt to gain a propaganda victory.

From 1943 onwards Switzerland stopped American and British aircraft, mainly bombers, overflying Switzerland on nine occasions, six times by Swiss Air Force fighters and nine by flak.

Thirty-six Allied airmen were killed.

On 1 October 1943 the first American bomber was shot down near Bad Ragaz, with only three men surviving.

The officers were interned in Davos and the airmen in Adelboden.

The representative of the US military intelligence group based in Bern, Barnwell Legge (a US military attaché to Switzerland), instructed the soldiers not to flee, but most of them thought it to be a diplomatic joke and gave no regard to his request.

As a neutral state bordering Germany, Switzerland was relatively easy to reach for refugees from the Nazis.

Switzerland’s refugee laws, especially with respect to Jews fleeing Germany, were strict and have caused controversy since the end of World War II.

From 1933 until 1944 asylum for refugees could only be granted to those who were under personal threat owing to their political activities only.

It did not include those who were under threat due to race, religion or ethnicity.

On the basis of this definition, Switzerland granted asylum to only 644 people between 1933 and 1945.

Of these, 252 cases were admitted during the war.

All other refugees were admitted by the individual cantons and were granted different permits, including a “tolerance permit” that allowed them to live in the canton but not to work.

Over the course of the war, Switzerland interned 300,000 refugees.

Of these, 104,000 were foreign troops interned according to the Rights and Duties of Neutral Powers outlined in the Hague Conventions.

The rest were foreign civilians and were either interned or granted tolerance or residence permits by the cantonal authorities.

Refugees were not allowed to hold jobs.

Of the refugees, 60,000 were civilians escaping persecution by the Nazis.

Of these 60,000, 27,000 were Jews.

Between 10,000 and 24,000 Jewish civilian refugees were refused entry.

These refugees were refused entry on the asserted claim of dwindling supplies.

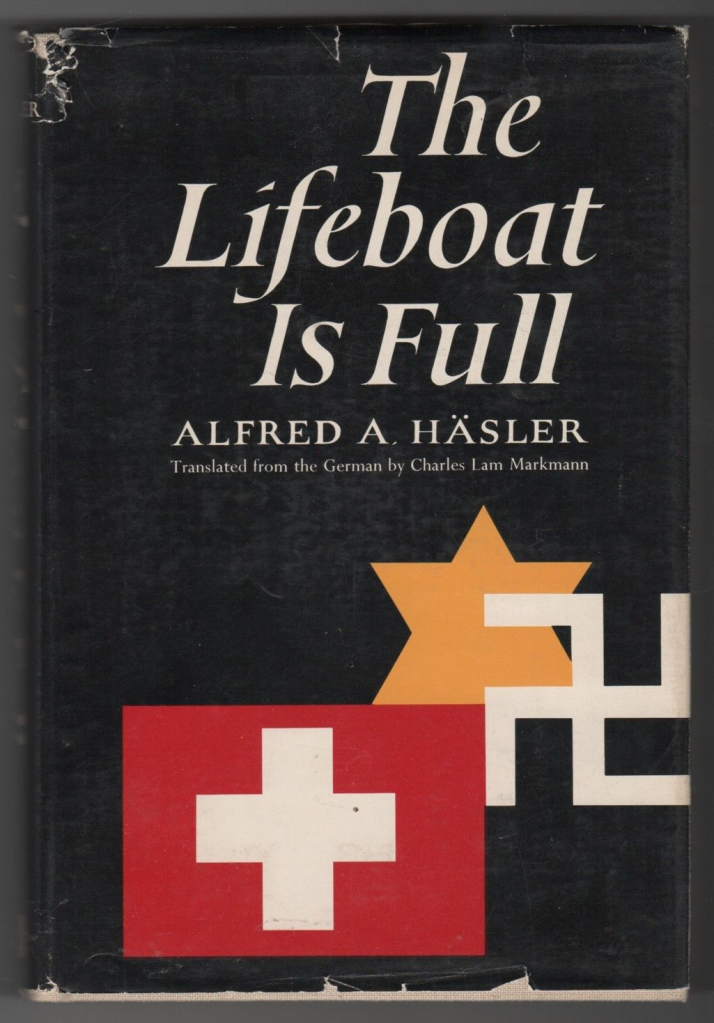

Of those refused entry, a Swiss government representative said:

“Our little lifeboat is full.”

At the beginning of the war, Switzerland had a Jewish population of between 18,000 and 28,000 and a total population of about 4 million.

By the end of the war, there were over 115,000 refuge-seeking people of all categories in Switzerland, representing the maximum number of refugees at any one time.

Switzerland’s treatment of Jewish refugees has been criticized by scholars of the Holocaust.

In 1999 an international panel of historians declared that Switzerland was “guilty of acting as an accomplice to the Holocaust when it refused to accept many thousands of fleeing Jews, and instead sent them back to almost certain annihilation at the hands of the Nazis“.

Jews were sent either to work or to the gas chamber.

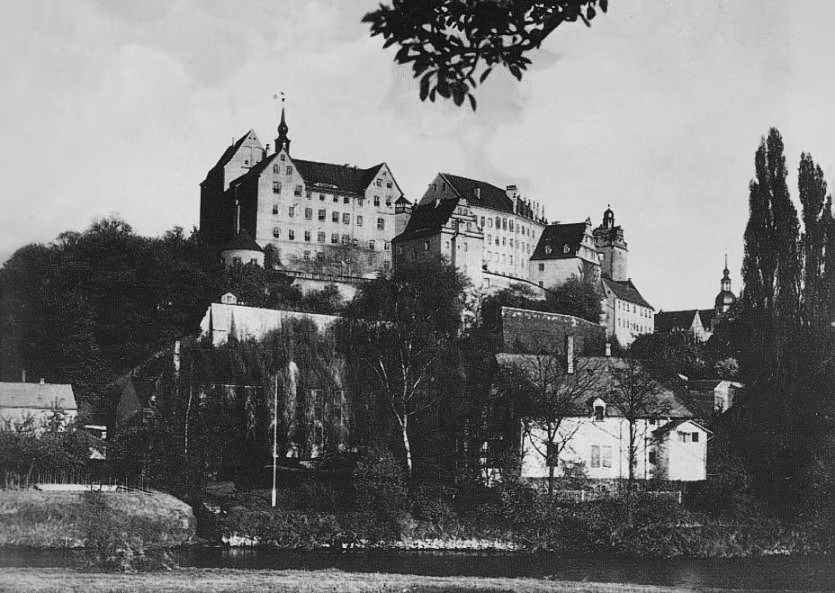

Switzerland also acted as a refuge for Allied POWs who escaped, including those from Colditz.

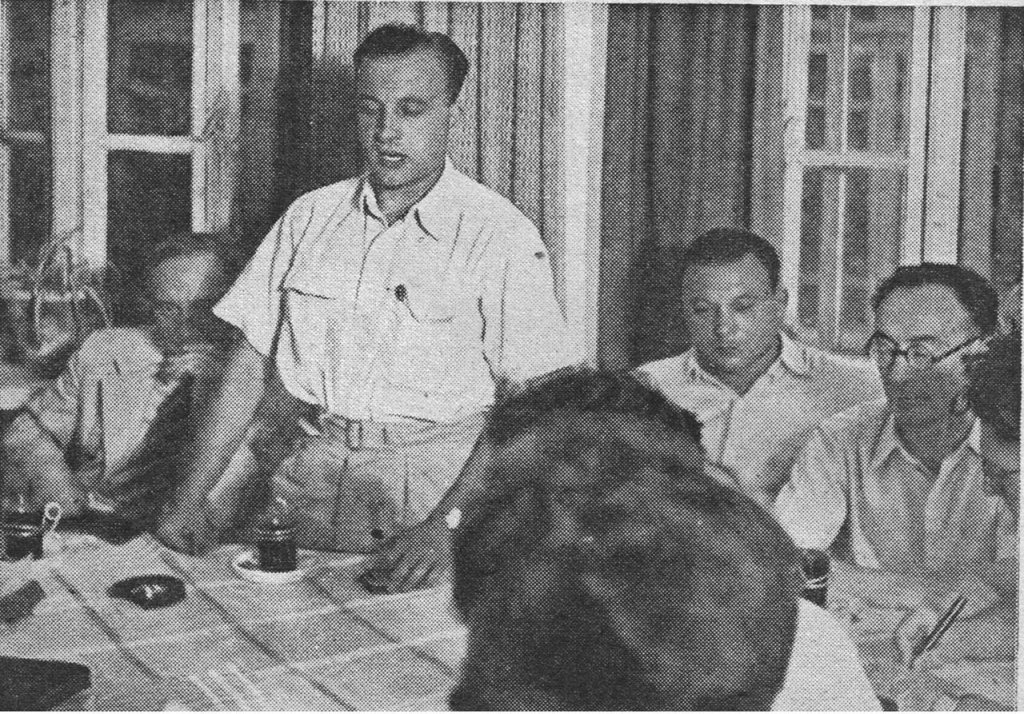

In 1939, the Service of Intellectual Assistance to Prisoners of War (SIAP) was created by the International Bureau of Education (IBE), a Geneva-based international organization dedicated to educational matters.

In collaboration with the Swiss Federal Council, who initially funded the project, and the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), the SIAP provided over half a million books to prisoners of war during World War II, and organized educational opportunities and study groups in prison camps.

Switzerland’s trade was blockaded by both the Allies and by the Axis.

Each side openly exerted pressure on Switzerland not to trade with the other.

Economic cooperation and extension of credit to the Third Reich varied according to the perceived likelihood of invasion, and the availability of other trading partners.

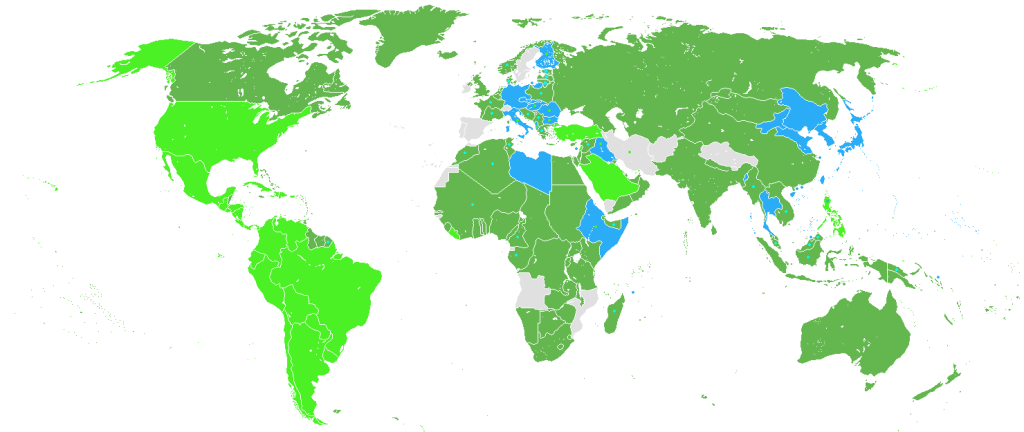

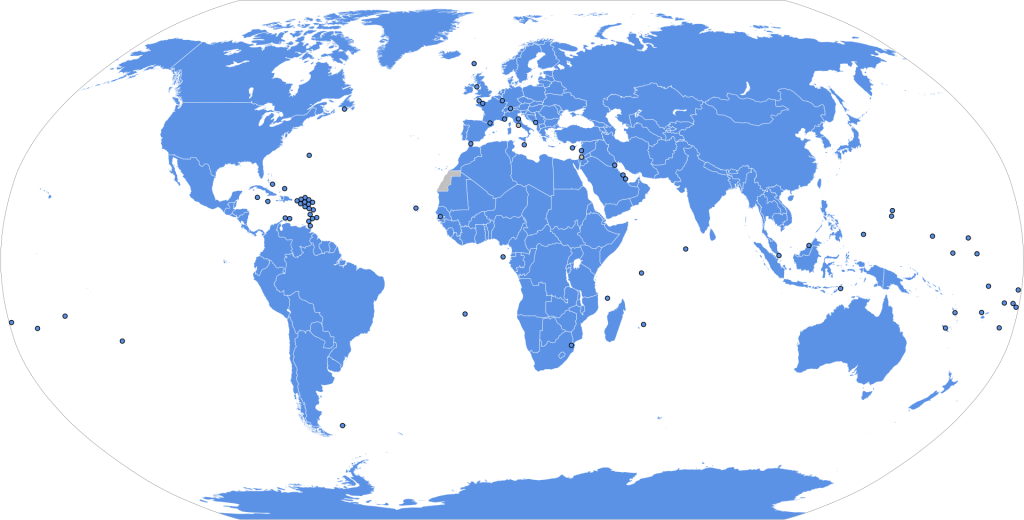

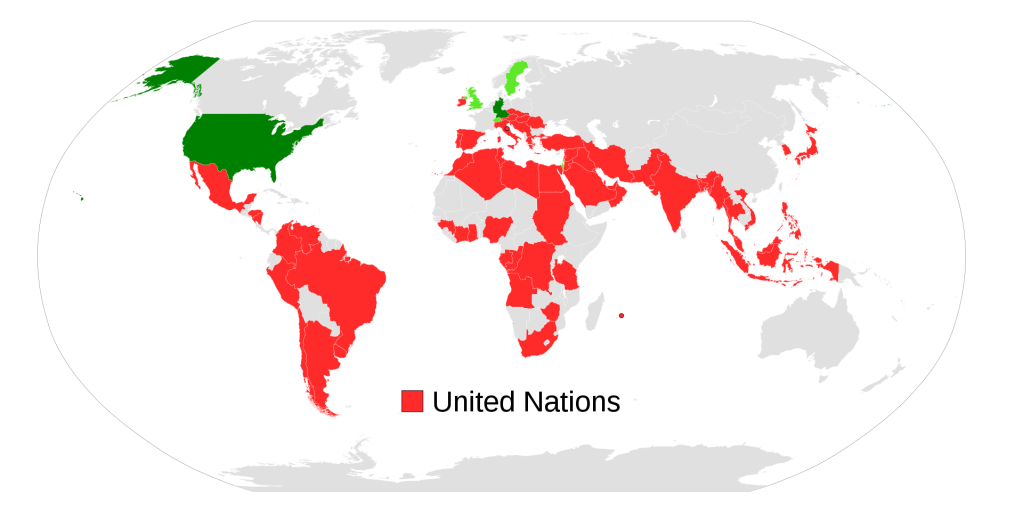

Dark Green: Allies before the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, including colonies and occupied countries

Light Green: Allied countries that entered the war after the attack on Pearl Harbor

Blue: Axis powers, their colonies and allies

Grey: Neutral countries during WW2

Dark green dots represent countries that initially were neutral but during the war were annexed by the USSR

Light green dots represent countries that later in the war changed from the Axis to the Allies Blue dots represent countries either being conquered by the Axis Powers, becoming puppets of those (Vichy France and several French colonies)

Concessions reached their zenith after a crucial rail link through Vichy France was severed in 1942, leaving Switzerland completely surrounded by the Axis.

Switzerland relied on trade for half of its food and essentially all of its fuel.

However, the Swiss controlled vital trans-alpine rail tunnels between Germany and Italy and possessed considerable electrical generating capacity that was relatively safe from air attack.

Switzerland’s most important exports during the war were precision machine tools, watches, jewel bearings (used in bomb sights), electricity, and dairy products.

Until 1936, the Swiss franc was the only remaining major freely convertible currency in the world.

Both the Allies and the Germans sold large amounts of gold to the Swiss National Bank.

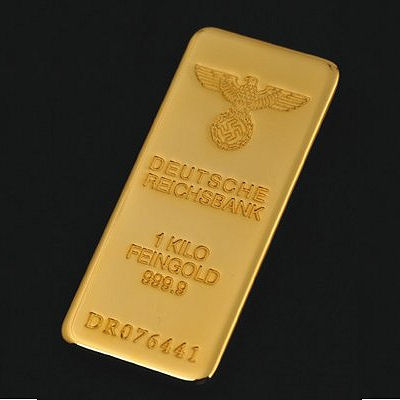

Between 1940 and 1945, the German Reichsbank sold 1.3 billion francs (approximately 18 billion francs adjusted for inflation to 2019) worth of gold to Swiss banks in exchange for Swiss francs and other foreign currency, which were used to buy strategically important raw materials like tungsten and oil from neutral countries.

Hundreds of millions of francs’ worth of this gold was monetary gold plundered from the central banks of occupied countries.

A total of 581,000 francs’ worth of “Melmer” gold taken from Holocaust victims in eastern Europe was sold to Swiss banks.

In the 1990s, a controversy over a class action lawsuit brought in Brooklyn, New York, over Jewish assets in Holocaust era bank accounts prompted the Swiss government to commission the most recent and authoritative study of Switzerland’s interaction with the Nazi regime.

The final report by this independent panel of international scholars, known as the Bergier Commission,was issued in 2002 and also documented Switzerland’s role as a major hub for the sale and transfer of Nazi-looted art during the Second World War.

Under pressure from the Allies, in December 1943 quotas were imposed on the importation and exportation of certain goods and foodstuffs and in October 1944 sales of munitions were halted.

However, the transit of goods by railway between Germany, Italy and occupied France continued.

North–South transit trade across Switzerland increased from 2.5 million tons before the war to nearly 6 million tons per year.

No troops or “war goods” were supposed to be transshipped.

Switzerland was concerned that Germany would cease the supply of the coal it required if it blocked coal shipments to Italy while the Allies, despite some plans to do so, took no action as they wanted to maintain good relations with Switzerland.

Between 1939 and 1945 Germany exported 10,267,000 tons of coal to Switzerland.

In 1943 these imports supplied 41% of Swiss energy requirements.

In the same period Switzerland sold electric power to Germany equivalent to 6,077,000 tons of coal.

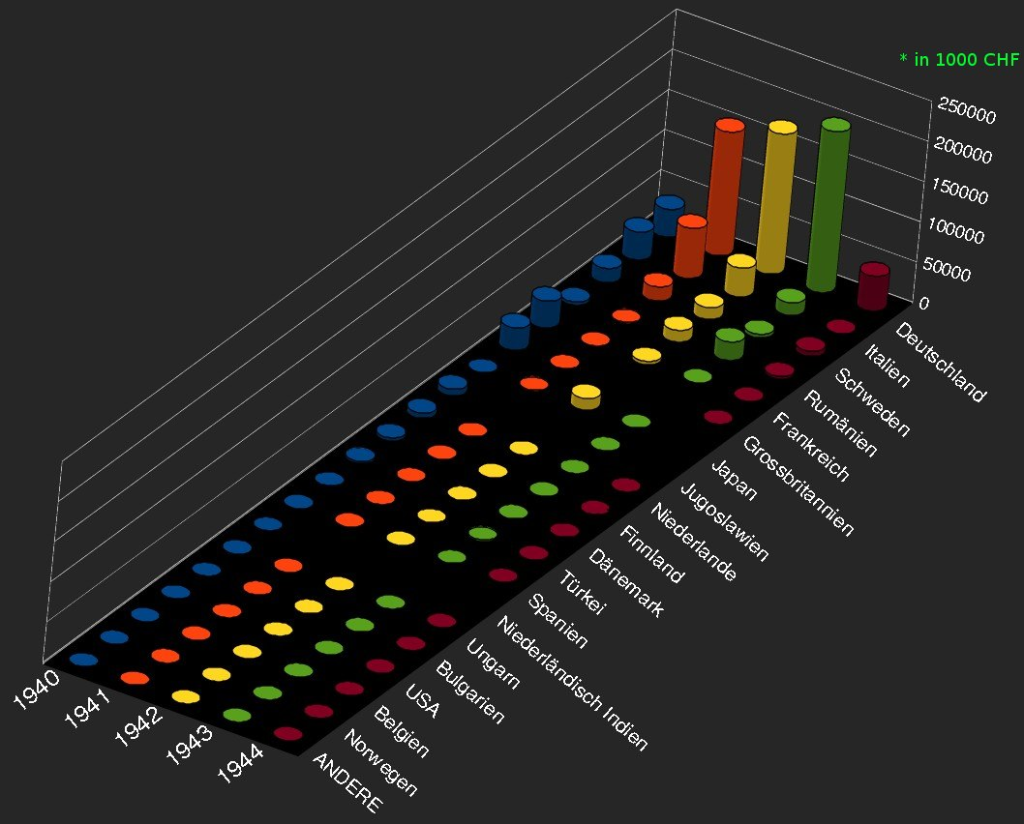

Above: Swiss exports of arms, ammunition, and fuses (thousands of CHF) (1940 – 1944)

Swiss neutrality is one of the main principles of Switzerland’s foreign policy which dictates that Switzerland is not to be involved in armed or political conflicts between other states.

This policy is self-imposed and designed to ensure external security and promote peace.

Switzerland has the oldest policy of military neutrality in the world.

It has not participated in a foreign war since its neutrality was established by the Treaty of Paris in 1815.

Although the European powers (Austria, France, the United Kingdom, Portugal, Prussia, Russia, Spain and Sweden) agreed at the Congress of Vienna (Wien) in May 1815 that Switzerland should be neutral, final ratification was delayed until after Napoleon Bonaparte was defeated so that some coalition forces Reformation could invade France via Swiss territory.

The country has a history of armed neutrality going back to the Reformation.

It has not been in a state of war internationally since 1815 and did not join the United Nations until 2002.

It pursues an active foreign policy and is frequently involved in peace-building processes around the world.

According to Swiss President Ignazio Cassis in 2022 during a World Economic Forum (WEF) speech, the laws of neutrality for Switzerland are based on the Hague agreement principles which include:

- no participation in wars

- international cooperation but no membership in any military alliance

- no provision of troops or weapons to warring parties

- no granting of transition rights

The beginnings of Swiss neutrality can be dated back to the defeat of the Old Swiss Confederacy at the Battle of Marignano in September 1515, or the peace treaty the Swiss Confederacy signed with France on 12 November 1516.

Prior to this, the Swiss Confederacy had an expansionist foreign policy.

The Peace of Westphalia in 1648 was another important step in the development of Switzerland’s neutrality.

Other countries were disallowed from passing through Swiss territory.

The Confederation became legally independent from the Holy Roman Empire, even though it had been independent from the Empire de facto since 1499.

The 1798 invasion of Switzerland by the French First Republic culminated in the creation of a satellite state called the Helvetic Republic.

While the 1798 Swiss constitution and the 1803 Act of Mediation stated that France would protect Swiss independence and neutrality, these promises were not kept.

With the latter act, Switzerland signed a defensive alliance treaty with France.

During the Restoration, the Swiss Confederation’s constitution and the Treaty of Paris’s Act on the Neutrality of Switzerland affirmed Swiss neutrality.

The dating of neutrality to 1516 is disputed by modern historians.

Prior to 1895, no historian referenced the Battle of Marignano as the beginning of neutrality.

The later backdating has to be seen in light of threats by several major powers in 1889 to rescind the neutrality granted to Switzerland in 1815.

A publication by Paul Schweizer, titled Geschichte der schweizerischen Neutralität (History of Swiss Neutrality) attempted to show that Swiss neutrality wasn’t granted by other nations, but a decision they took themselves and thus couldn’t be rescinded by others.

The later publication of the same name by Edgar Bonjour, published between 1946 and 1975, expanded on this thesis.

Following World War II, Switzerland began taking a more active role in humanitarian activities.

It joined the United Nations after a March 2002 referendum.

Ten years after Switzerland joined the UN, in recorded votes in the UN General Assembly, Switzerland occupied a middle position, siding from time to time with member states like the United States and Israel, but at other times with countries like China.

In the UN Human Rights Council Switzerland sided much more with Western countries and against countries like China and Russia.

Switzerland participated in the development of the International Code of Conduct for Private Security Service Providers, intended as an oversight mechanism of private security providers.

In September 2015, a “Federal Act on Private Security Services provided Abroad” was introduced, in order to “preserve Swiss neutrality“, as stated in its first article.

It requires Switzerland-based private security companies to declare all operations conducted abroad, and to adhere to the Code.

Moreover, it states that no physical or moral person falling under this law can participate directly — or indirectly through the offer of private security services — in any hostilities abroad.

In 2016, the Section of Private Security Services (SPSS), an organ of the Federal Department of Foreign Affairs in charge of the procedures defined by the new law, has received 300 approval requests.

In 2011, Switzerland registered as a candidate for a seat on the UN Security Council in 2023 – 2024.

In a 2015 report requested by Parliament, the government stated that a Swiss seat on the Security Council would be “fully compatible with the principles of neutrality and with Switzerland’s neutrality policy“.

Opponents of the project, such as former ambassador Paul Widmer, consider that this seat would “put its [Switzerland] neutrality at risk“.

A 2018 survey found that 95% of Swiss were in favor of maintaining neutrality.

In 2022, Switzerland imposed sanctions against Russia in response to the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

While Switzerland follows defined rules to remain neutral, it imposed sanctions for this “serious violation of the most fundamental norms of international law within the scope of its political room for manoeuvre“.

According to Federal Councilor Viola Amherd, Switzerland will not allow direct shipments of arms to the war zone from or through its territory.

Irrespective of the actual laws governing a neutral country, many media outlets still labelled this as a break with 500 years of Swiss neutrality.

In February 2022, Switzerland further adopted the sanctioning of Russia by the European Union and froze many Russian bank accounts.

Analysts said the move would affect the Swiss economy.

In April 2022, the Federal Department of Economic Affairs vetoed Germany’s request to re-export Swiss ammunition to Ukraine on the basis of Swiss neutrality.

The defence ministry of Switzerland, initiated a report in May 2022 analyzing various military options, including increased cooperation and joint military exercises with NATO.

A public opinion poll from March 2022 found that 27% of those surveyed supported Switzerland joining NATO, while 67% were opposed.

Another from May 2022 indicated 33% of Swiss supported NATO membership for Switzerland.

56% supported increased ties with NATO.

Swiss neutrality has been questioned at times, notably regarding Switzerland’s role during the Second World War and the International Committee of the Red Cross, the looted Nazi gold (and later during Operation Gladio), its economic ties to the apartheid regime in South Africa, and more recently in the Crypto AG espionage case.

Operation Gladio is the codename for clandestine “stay behind” operations of armed resistance that were organized by the Western Union (WU)(1948 – 1954), and subsequently by NATO and the CIA, in collaboration with several European intelligence agencies.

The operation was designed for a potential Warsaw Pact invasion and conquest of Europe.

Although Gladio specifically refers to the Italian branch of the NATO stay-behind organizations, “Operation Gladio” is used as an informal name for all of them.

Stay-behind operations were prepared in many NATO member countries, and some neutral countries.

During the Cold War, some anti-Communist armed groups engaged in the harassment of left wing parties, torture, terrorist attacks, and massacres in countries such as Italy.

The role of the CIA and other intelligence organisations in Gladio — the extent of its activities during the Cold War era and any responsibility for terrorist attacks perpetrated in Italy during the “Years of Lead” (1968 – 1988) — is the subject of debate.

In 1990, the European Parliament adopted a resolution alleging that military secret services in certain member states were involved in serious terrorism and crime, whether or not their superiors were aware.

The resolution also urged investigations by the judiciaries of the countries in which those armies operated, so that their modus operandi and actual extension would be revealed.

To date, only Italy, Switzerland and Belgium have had parliamentary inquiries into the matter.

The three inquiries reached differing conclusions as regarded different countries.

Guido Salvini, a judge who worked in the Italian Massacres Commission, concluded that some right-wing terrorist organizations of the Years of Lead – La Fenice, National Vanguard and Ordine Nuovo – were the trench troops of a secret army, remotely controlled by exponents of the Italian state apparatus and linked to the CIA.

Salvini said that the CIA encouraged them to commit atrocities.

The Swiss inquiry found that British intelligence secretly cooperated with their army in an operation named P-26 and provided training in combat, communications, and sabotage.

It also discovered that P-26 not only would organize resistance in case of a Soviet invasion, but would also become active should the left succeed in achieving a parliamentary majority.

The Belgian inquiry could find no conclusive information on their army.

No links between them and terrorist attacks were found, and the inquiry noted that the Belgian secret services refused to provide the identity of agents, which could have eliminated all doubts.

A 2000 Italian parliamentary report from the left wing coalition Gruppo Democratici di Sinistra l’Ulivo reported that terrorist massacres and bombings had been organised or promoted or supported by men inside Italian state institutions who were linked to American intelligence.

The report also said the United States was guilty of promoting the strategy of terrorism.

Operation Gladio is also suspected to have been activated to counter existing left-wing parliamentary majorities in Europe.

The US State Department published a communiqué in January 2006 that stated claims the United States ordered, supported, or authorized terrorism by stay-behind units, and US-sponsored “false flag” operations are rehashed former Soviet disinformation based on documents that the Soviets forged.

The word gladio is the Italian form of gladius, a type of Roman short sword.

Crypto AG was a Swiss company specialising in communications and information security founded by Boris Hagelin in 1952.

The company was secretly purchased for US $5.75 million and jointly owned by the American CIA and West German Federal Intelligence Service (BND) from 1970 until about 1993, with the CIA continuing as sole owner until about 2018.

The mission of breaking encrypted communication using a secretly owned company was known as “Operation Rubikon“.

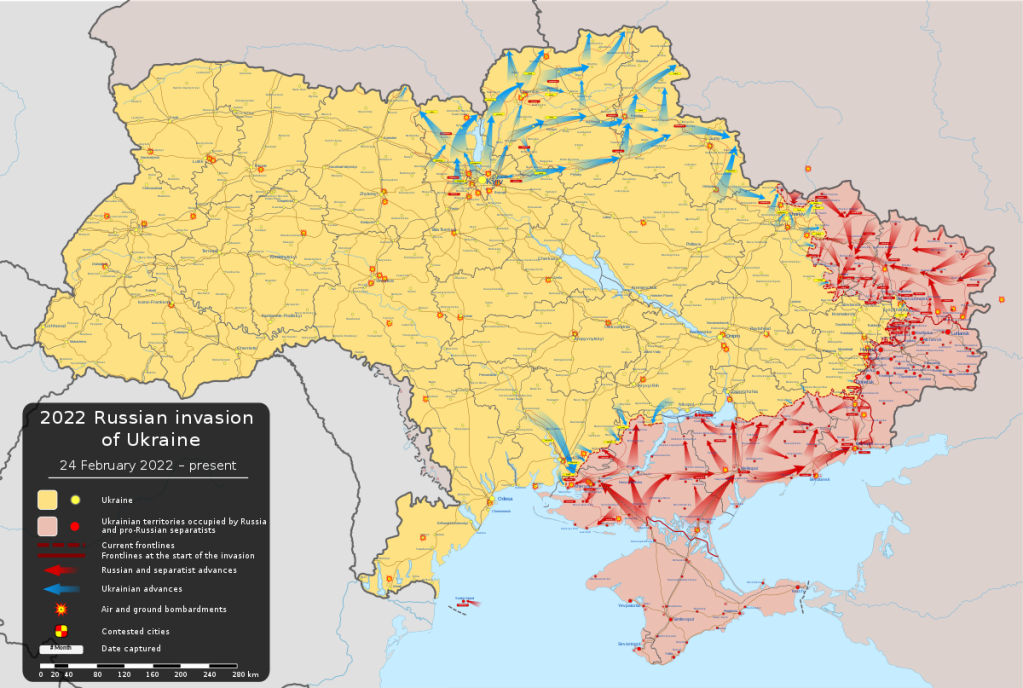

(dark green) Spying countries / (light green) Knowing countries / (red) Nations spied upon

With headquarters in Steinhausen, the company was a long-established manufacturer of encryption machines and a wide variety of cipher devices.

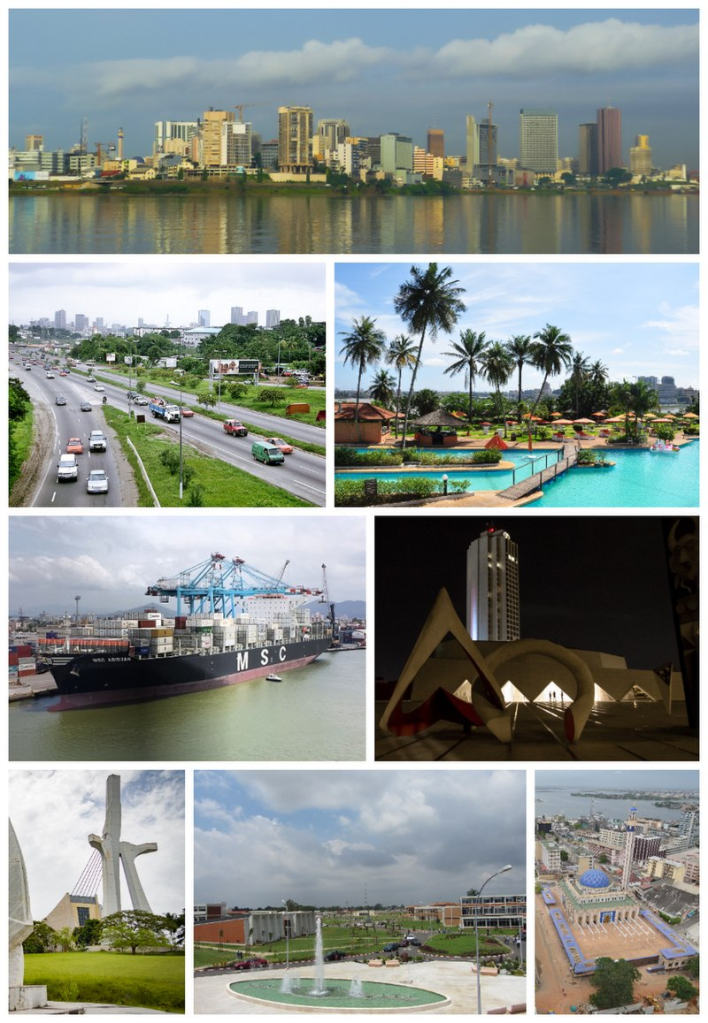

The company had about 230 employees, had offices in Abidjan, Abu Dhabi, Buenos Aires, Kuala Lumpur, Muscat, Selsdon and Steinhausen, and did business throughout the world.

The owners of Crypto AG were unknown, supposedly even to the managers of the firm.

They held their ownership through bearer shares.

The company has been criticized for selling backdoored products to benefit the American, British and German national signals intelligence agencies, the National Security Agency (NSA), the Government Communications Headquarters (GCHQ) and the BND, respectively.

On 11 February 2020, the Washington Post, ZDF and SRF revealed that Crypto AG was secretly owned by the CIA in a highly classified partnership with West German intelligence, and the spy agencies could easily break the codes used to send encrypted messages.

The operation was known first by the code name “Thesaurus” and later “Rubicon“.

According to a Swiss parliamentary investigation:

“Swiss intelligence services were aware of and benefited from the Zug-based firm Crypto AG’s involvement in the US-led spying.”

This is neutrality?

Honestly, my (albeit, amateur) opinion is that after the Swiss learned that waging war is more expensive than making wages from war, Swiss allegiance is as predictable as the direction of an airport’s wind sock – everything depends on which way the winds of change are blowing and what can generate the most profit.

Granted that war is truly something to be avoided, but there are times in the affairs of men that action is needed even if that action may mean that your side might lose.

I view the Switzerland of today no differently than the Switzerland of yesterday:

Mercantile, mercenary, Machiavellian in its machinations.

How the conduct and conscience of a nation connect with Thurgau’s second city is reflected in the weather vane direction switch that Kreuzlingen has showed over the decade when I was a resident of nearby Landschlacht.

It seemed almost on a weekly basis that either the Thurgauer Zeitung, the Kreuzlinger Nachrichten or the Kreuzlinger Zeitung would write editorials complaining vehemently how the region was being invaded and dominated by Germans and other foreigners buying lakeside property and dominating local business in much the same manner as occurred before World War 1.

Then the coronavirus struck and the border between Kreuzlingen and Konstanz was sealed.

Suddenly, Kreuzlingers were singing a different tune – how wonderful the Germans were, how beneficial the open border was for both nations, how eager everyone was for international trade and relations to resume.

Say what one will about the Germans, but at least they, rightly or wrongly, seem far more honest and steadfast and transparent than their Swiss counterparts.

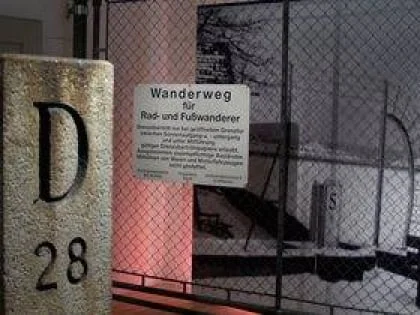

Above: The border between Germany (north) and Switzerland (south)

The fact that Kreuzlingen Abbey was deliberately torched twice suggests that distrusting the Swiss was not unique to the times nor to the residents of Konstanz.

Kreuzlingen invariably reminds me of Gatineau, Québec, across the Ottawa River from Ottawa, Ontario, Canada’s federal capital.

Gatineau definitely benefits from Ottawa as a major employer of its residents and yet often the Québec nationalist sentiments flow more strongly through Gatineau thought than the River that separates the two cities.

Kreuzlingen has a population (as of December 2020) of 22,390.

As of 2008, 48.1% of the population are foreign nationals.

Over the last 10 years (1997 – 2007) the population has changed at a rate of 2.2%.

Most of the population (as of 2000) speaks German (79.7%), Italian (5.2%) and Albanian (3.8%).

In all my visits to Kreuzlingen I have heard and spoken only German.

At first glance the casual observer might wonder why the Germans would move to Kreuzlingen when almost everything in Switzerland is far more expensive than is found in Germany.

But it seems for many professions working conditions are better in the Confederation than in the Republic.

This was the case for my wife’s profession.

The opposite was true for mine.

I reckon the next question should be whether Kreuzlingen is worth visiting at all.

Here is what Kreuzlingen has to offer the tourist:

- Five churches:

- Ten castles:

- Museums:

- Two Stölpersteine (stumbling blocks) found on Schläferstrasse in memory of those who were persecuted by the Nationalist Socialist Party

At Schäflerstrasse 11:

Ernst Bärtschi (1903 – 1983) was born in Tuttlingen, Germany.

He was a Swiss citizen, like his father, a shoemaker from Dulliken in canton Solothurn, who worked in Germany building the Black Forest Railway and married a woman from Tuttlingen.

Ernst Bärtschi and his German friends Karl Durst and Andreas Fleig smuggled political pamphlets and brochures from 1933 onwards.

Later he helped countless emigrants to flee to Switzerland.

In 1938, he and his comrades-in-arms fell into a Gestapo trap and were sentenced to 13 years in prison.

Shortly before the end of the war he was liberated by the Americans.

Bärtschi died in Scherzingen in canton Thurgau.

At Schäflerstrasse 7:

Andreas Fleig (1884 – 1971) was born in Sulz an der Lahr, Germany.

His parents were the carpenter Nikolaus Fleig and his wife Elisabeth.

He had several siblings and also learned the carpenter’s trade.

He moved to Konstanz, joined the German Woodworkers’ Association in 1904 and was a member of the SPD from 1910 to 1914.

In 1912 he moved to the Thurgau community of Kreuzlingen and worked for Jonasch & Cie, which manufactured seating furniture.

He married Wilhelmine Friedricke née Bleich and the couple had one son, Karl Andreas.

During the First World War he served in the German army from 1915 to 1918, but did not return to the troops from a home leave in 1918 and stayed in Switzerland.

In 1928, he bought a small house at Schäflerstrasse 7 in Kreuzlingen for around 15,000 francs.

A local councilor described him as a:

“Swabian of real buck and grain.

Efficient at work and helpful in life.»

Fleig was a declared opponent of National Socialism and kept in touch with trade unionists and social democrats.

As early as 1933 he was wanted by the Gestapo.

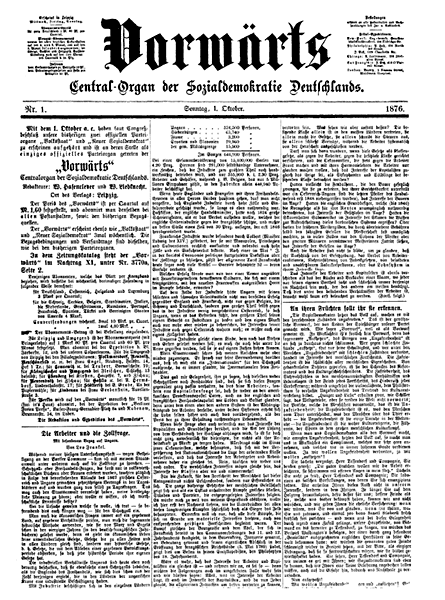

Together with his work colleagues and friends Josef Anselm and Karl Durst from Konstanz and his neighbor, the aluminum worker Hermann Ernst Bärtschi, he smuggled political brochures and magazines – such as Der Funke, afa Nachrichten or the Neue Vorwärts – from Switzerland to Germany.

He also worked with his friends as a courier for emigrant mail from Switzerland to Germany and also obtained border permits, which he used to steer persecuted officials of the German labour movement across the border.

For example, he saved the SPD Reichstag deputy Hans Unterleitner, who was interned in the Dachau concentration camp from 1933 to 1935, and his family.

When on 8 May 1938, together with Bärtschi and Durst, he tried to bring the persecuted trade union functionary Hans Lutz across the border, all three escape helpers were arrested.

Under torture, Lutz had revealed all the names of the Funkentruppe.

Also arrested were Josef Anselm, Paulina Gutjahr and Bruno W. Schlegel, the other members of the resistance group.