Eskişehir, Türkiye, Wednesday 6 July 2022

On a typical pandemic afternoon, thousands of noncombatants watched from the sidelines as their General ordered his troops across the battlefield and became locked in a fierce duel with the enemy.

At one point the General berated himself for a tactical misstep that cost have cost his side the high stakes conflict.

Then he smiled and began outmaneuvering his foe.

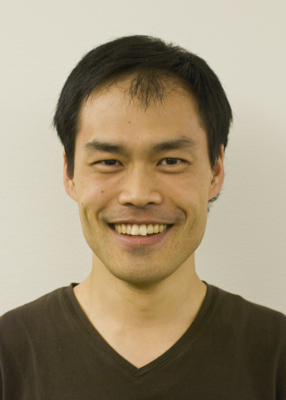

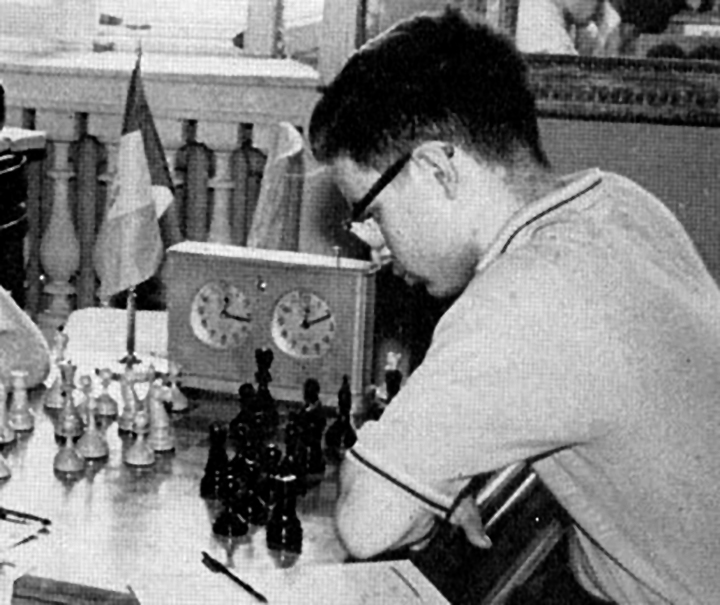

“I can’t lose.“, Hikaru Nakamura (32) said to the exultant onlookers.

Victory seemed close as members of the opposing army were vanquished one by one.

“I win again – there you go, guys. Wow.“

Nakamura gave himself just a moment’s respite, then plunged into another fray.

Pawns, knights, bishops and even kings fell before him as the chess grandmaster demolished a slate of online challengers, all while narrating the tide of the battle to tens of thousands of fans watching him stream live on Twitch, the Amazon-owned site where people usually broadcast themselves playing video games like Fortnite and Call of Duty.

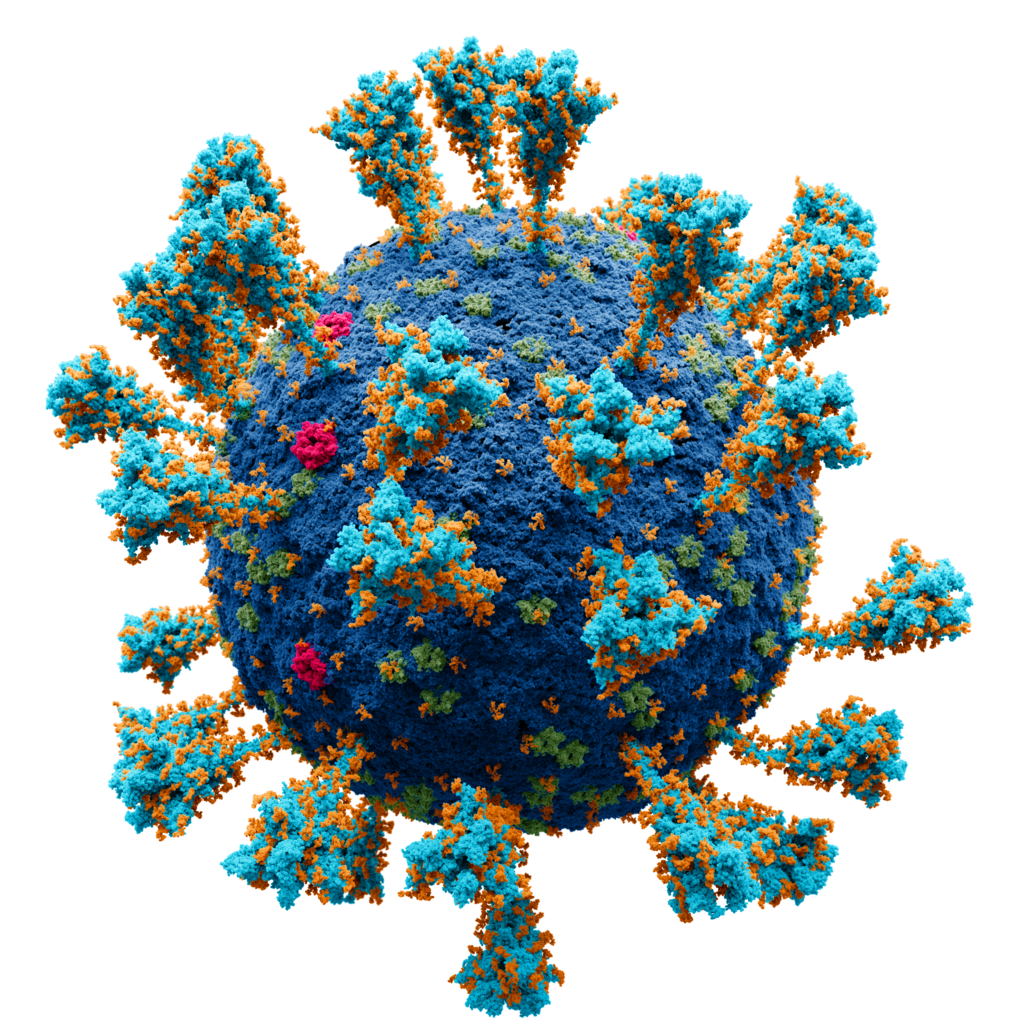

The corona virus pandemic and stay-at-home orders crowned a host of unlikely winners catering to bored audiences, but watching livestreams of chess games?

Could one of the world’s oldest and most cerebral games really rebrand itself as a lively enough pastime to capture the interest of the masses on Twitch?

It did.

Since the pandemic began (and truth be admitted it has not really gone away, despite many countries acting as if it has), viewership of live chess games has soared.

From March through August 2020, people watched 41.2 million hours of Twitch, four times as many hours as in the previous six months, according to analytics website SullyGnome.

In June 2020, an amateur chess tournament called PogChamps was briefly the top-viewed stream on Twitch, with 63,000 people watching at once, SullyGnome said.

And popular Twitch gamers like Félix Lengyel (better known to his 3.3 million followers as “xQcOW“) have also recently started streaming chess.

That collision of the chess audience and the general gamer audience has created a “giant chess bonfire“, said Marcus Graham, Twitch‘s head of creator development.

The popularity of online chess has partly been fueled by Nakamura.

Last month, one of the world’s top professional video game teams, Team SoloMid, beat several e-sports rivals to sign him to a six-figure contract so it could pair him with advertisers and merchandise.

Nakamura was one of the first chess players to join an e-sports team, just a week after a different group signed a Canadian player, Qiyu Zhou.

Though Nakamura began streaming chess consistently on his Twitch channel, GMHikaru, in 2018, nearly all of his 528,000 followers have come aboard since the pandemic began.

And as his popularity has skyrocketed, media attention has increased – including a cameo of himself on the TV drama Billions in May.

“It is just amazing to see the level of support and the love that I have seen from the Twitch community.“, Nakamura said.

He added that the most appealing part of playing and streaming chess was simply “the fact that I am so good at it“.

It helps that he has an unimpeachable chess pedigree.

In 1998, at age 10, he became the youngest player in the United States to be named a Master, a title earned through strong performances.

Five years later, he became the youngest US player to graduate to Grandmaster, the highest title.

He has since won five national championships.

On his Twitch channel, Nakamura, who lives in Los Angeles, rarely stops talking.

His stream of commentary and chatter, even as he directs his pieces with the precision of an orchestra conductor, is one of the main reasons fans have flocked to him.

“He draws people because he is so good, but also, there are other top players on Twitch that are not as engaging as he is, not as funny, not as in tune with the sort of Twitch culture.“, said Brandon Benton (34), a post-doctorial physics researcher at Cornell University who watches Nakamura stream.

“He is a down-to-earth memer and jokester.“

If you are picturing a chess match as a drawn-out slog…..

Well, you are not wrong.

A classical game without time limits can last five hours, but many online battles, including nearly all the games that Nakamura streams are blitz chess.

Each player has just a few minutes to complete their moves, leading to an aggressive, risky style of play that fans say is exhilarating to watch.

A player’s timer stops only when it is the other person’s turn to move a piece, so planning ahead and making quick calls is vital to managing the clock.

The climax often comes when mere seconds remain and the combatants exchange a rapid flurry of moves.

In an August 2020 stream, Nakamura had fewer pieces left than his opponent and just 20 seconds remaining, but 41 moves later, he was grinning after pulling off an improbable checkmate that involved charging a pawn across the board and hatching it into a queen.

It had taken him just 16 seconds.

“More than anything, it is the ability to play extremely high-level chess and win while I seemingly am not focused on the game and talking to my chat.“, Nakamura said of his ability to draw a large audience, which he usually retains as he plays more than 20 or more games in one sitting.

“At least at blitz chess, I am probably the best or second-best player ever, in the entire history, at least online.“

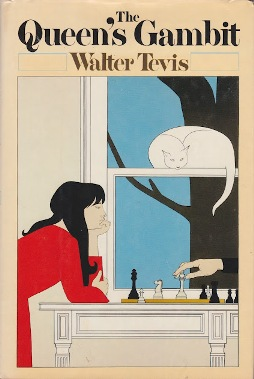

Also in 2020, another factor in the rise in popularity of chess was The Queen’s Gambit, an American coming-of-age period drama streaming TV miniseries based on the 1983 novel of the same name by Walter Tevis.

The title refers to the “Queen’s Gambit“, a chess opening.

Beginning in the mid-1950s and proceeding into the 1960s, the story follows the life of Beth Harmon (Anya Taylor-Joy), a fictional chess prodigy on her rise to the top of the chess world while struggling with drug and alcohol dependency.

Netflix released The Queen’s Gambit on 23 October 2020.

After four weeks it had become Netflix’s most-watched – including by my wife – scripted miniseries, making it Netflix’s top program in 63 countries.

The series received critical acclaim, with particular praise for Taylor-Joy’s performance, the cinematography, and production values.

It also received a positive response from the chess community for its accurate depictions of high-level chess, and data suggests that it increased public interest in the game.

I will be honest.

I am no Nakamura now nor Harmon here.

Friends and family taught me the game, but never taught me how to win.

Nor taught me to invest a lot of emotion or time in the game.

Here the pieces are represented by riders upon elephants, horses & camels predating the European Staunton design.

In the Middle Ages and during the Renaissance, chess was a part of noble culture.

It was used to teach war strategy and was dubbed “the King’s Game“.

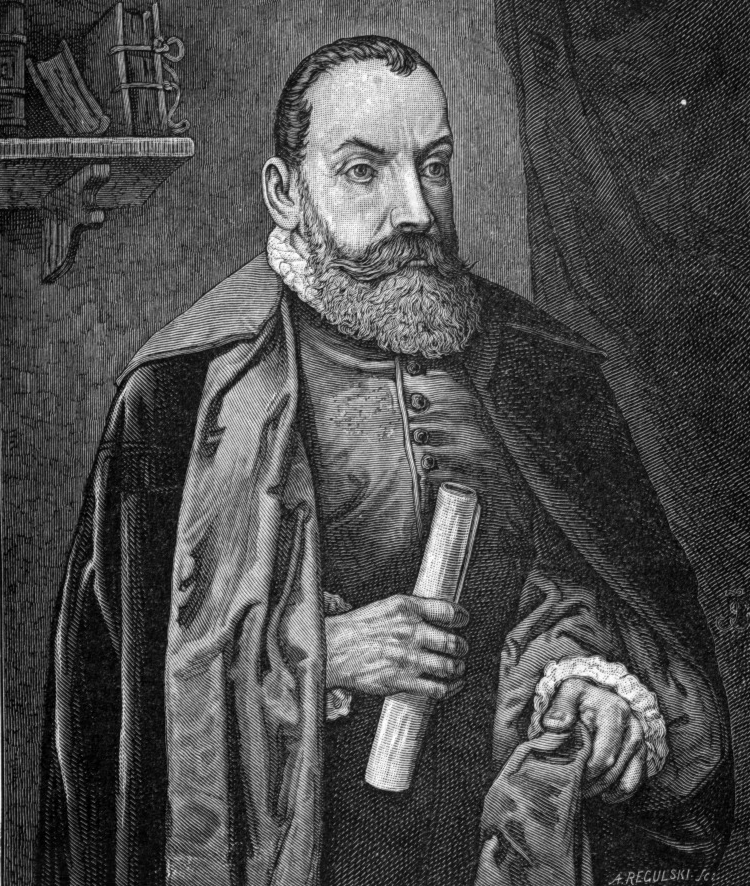

Chess or the King’s Game (Das Schach- oder Königsspiel) (1616) is a book on chess, which was published in Leipzig under the name of Gustavus Selenus, the pen name of Duke Augustus.

As a young prince, Augustus probably had learned of the game during his voyages to Italy and purchased numerous chess books from the Augsburg merchant and art collector Philipp Hainhofer.

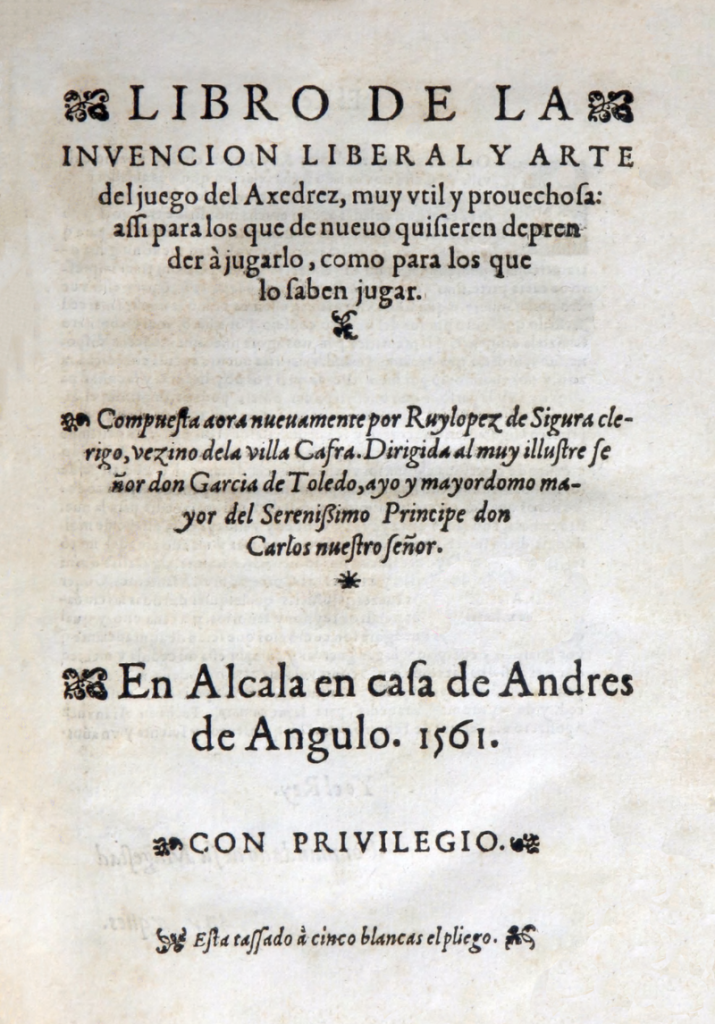

The first textbook on chess in the German language, Chess is mainly based on the Libro de la invencion liberal y arte del juego del axedrez (1561) by the Spanish priest Ruy López de Segura.

Chess also contains extensive philosophical and historical considerations (e.g. on the “chess village” of Ströbeck).

In addition to chess instruction, Chess contained interesting illustrations of contemporary German chess pieces.

The usage for chessmen at the time tended to favour slender designs with nested floral crowns.

The book was so successful that pieces of this pattern became known as the “Selenus chess sets”.

Over time, pieces became taller, thinner, and more elaborate.

Their apparent floral nature lead some to name them “Garden chess sets” or “Tulip chess sets“.

Selenus pattern sets were commonly made in Germany and Central Europe until about 1914 when they were completely eclipsed by the more playable and stable Staunton chess set pattern, introduced in 1849 by manufacturer Jaques of London.

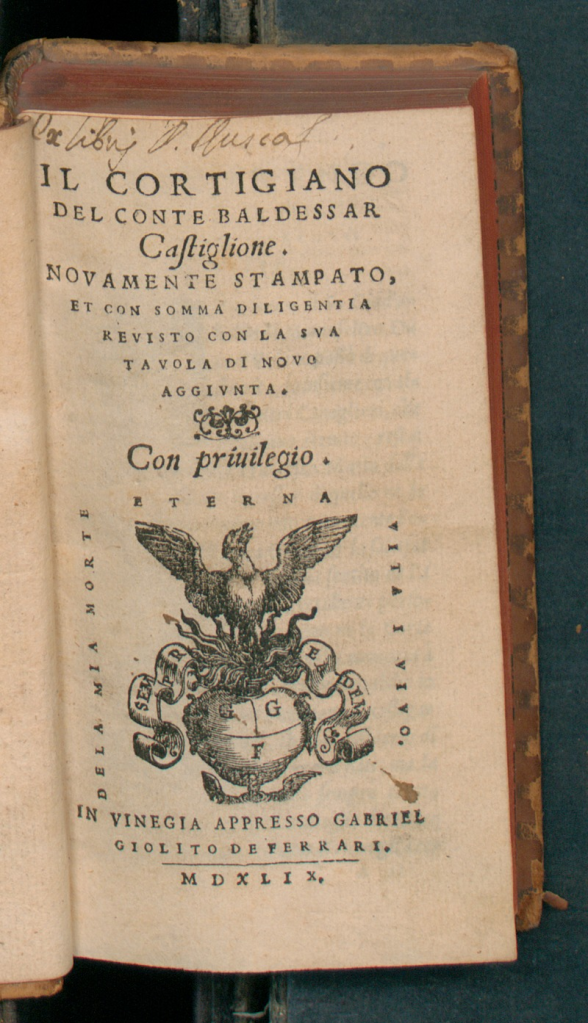

Gentlemen are “to be mainly seen in the play at Chess“, says the overview at the beginning of Baldassare Castiglione’s The Book of the Courtier (1528), but chess should not be a gentleman’s main passion.

Castiglione explains it further:

“And what say you to the game at chess?

It is truly an honest kind of entertainment and witty, quotes Sir Frederick.

But I think it has a fault, which is, that a man may be to counting at it, for whoever will be excellent in the play of chess, I believe he must bestow much time about it, and apply it with so much study, that a man may as soon learn some noble science, or compass any other matter of importance, and yet in the end in bestowing all that labour, he knows no more but a game.

Therefore in this I believe there happens a very rare thing, namely, that the mean is more commendable, then the excellency.“

Chess was often used as a basis of sermons on morality.

An example is Liber de moribus hominum et officiis nobilium sive super ludo scacchorum (‘Book of the customs of men and the duties of nobles or the Book of Chess‘), written by an Italian Dominican monk Jacobus de Cessolis in 1300.

This book was one of the most popular of the Middle Ages.

The work was translated into many other languages (the first printed edition was published at Utrecht in 1473) and was the basis for William Caxton’s The Game and Play of Chess (1474), one of the first books printed in English.

Different chess pieces were used as metaphors for different classes of people, and human duties were derived from the rules of the game or from visual properties of the chess pieces:

“The knight ought to be made all armed upon an horse in such wise that he have a helmet on his head and a spear in his right hand, and covered with his shield, a sword and a mace on his left side, clad with an halberd and plates to cover his breast, leg harness on his legs, spurs on his heels, on his hands his gauntlets, his horse well broken and taught and apt to battle and covered with his armour.

When the knights have been bathed in blood, that is the sign that they should lead a new life and new manners.

Also they wake all the night in prayers and orations unto God that He will give him grace that they may get that thing that they may not get by nature.

The king or prince girds about them a sword in sign that they should abide and keep him of whom they take their dispenses and dignity.“

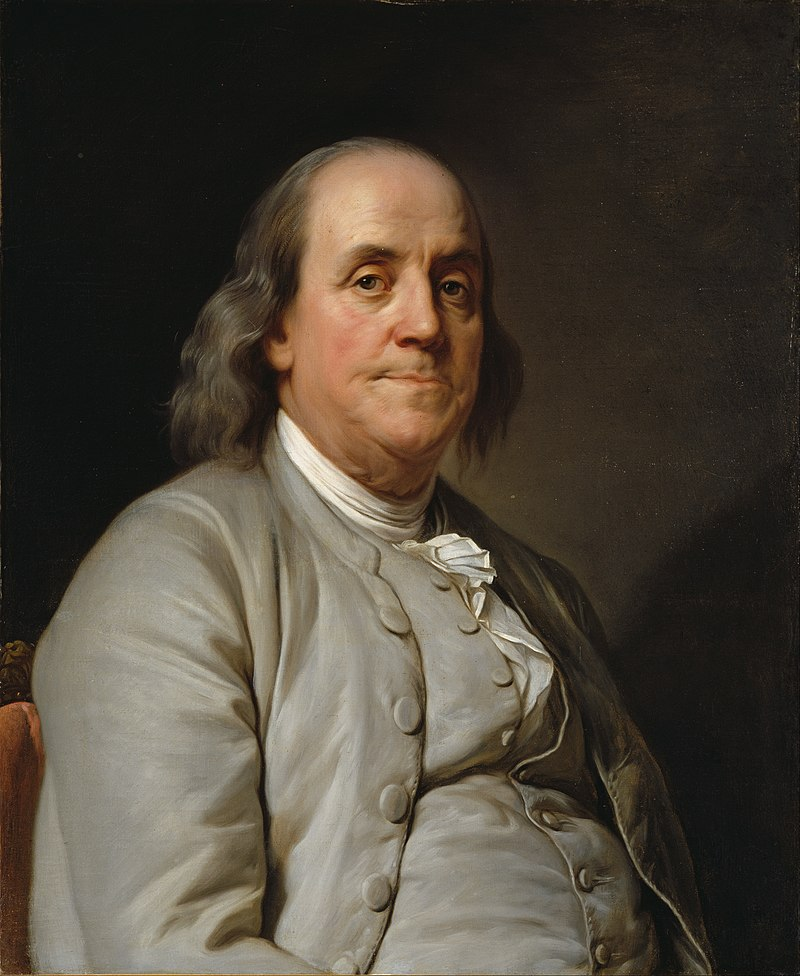

During the Age of Enlightenment (17th / 18th centuries), chess was viewed as a means of self-improvement.

Benjamin Franklin, in his article “The Morals of Chess” (1750), wrote:

“The game of chess is not merely an idle amusement. Several very valuable qualities of the mind, useful in the course of human life, are to be acquired and strengthened by it, so as to become habits ready on all occasions.

For life is a kind of chess, in which we have often points to gain, and competitors or adversaries to contend with, and in which there is a vast variety of good and ill events, that are, in some degree, the effect of prudence, or the want of it.

By playing at chess then, we may learn:

I. Foresight: which looks a little into futurity, and considers the consequences that may attend an action

II. Circumspection: which surveys the whole chess board, or scene of action: – the relation of the several pieces and their situations

III. Caution: not to make our moves too hastily“

Chess was occasionally criticized in the 19th century as a waste of time.

Chess is taught to children in schools around the world today.

Many schools host chess clubs and there are many scholastic tournaments specifically for children.

Tournaments are held regularly in many countries, hosted by organizations such as the US Chess Federation and the National Scholastic Chess Foundation.

Chess is many times depicted in the arts.

Chess became a source of inspiration in the arts in literature soon after the spread of the game to the Arab world and Europe in the Middle Ages.

The earliest works of art centered on the game are miniatures in medieval manuscripts, as well as poems, which were often created with the purpose of describing the rules.

After chess gained popularity in the 15th and 16th centuries, many works of art related to the game were created.

In the Palatine Chapel of the Norman Palace in Palermo you can admire the first painting of a chess game that is known to the world.

The work dates from around 1143 and the artists who created the Muslim players were chosen by the Norman king of Sicily Roger II of Hauteville, who erected the church.

As the popularity of the game became widespread during the 15th and 16th centuries, so too did the number of paintings depicting the subject.

Continuing into the 20th century, artists created works related to the game often taking inspiration from the life of famous players or well-known games.

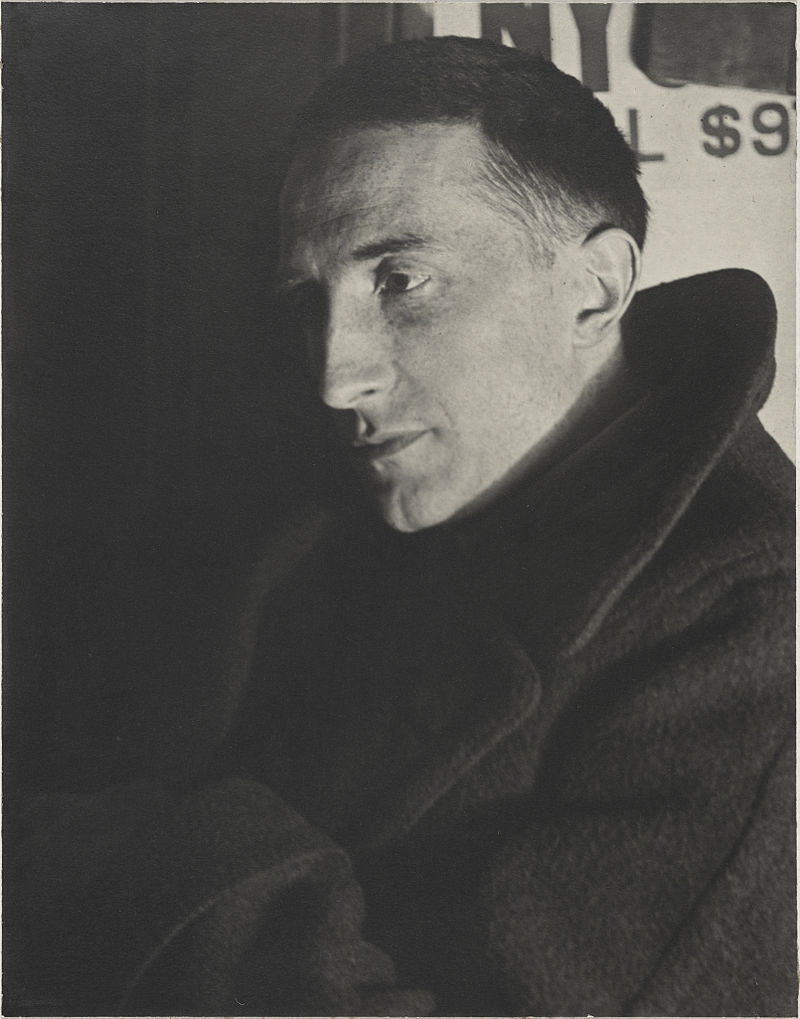

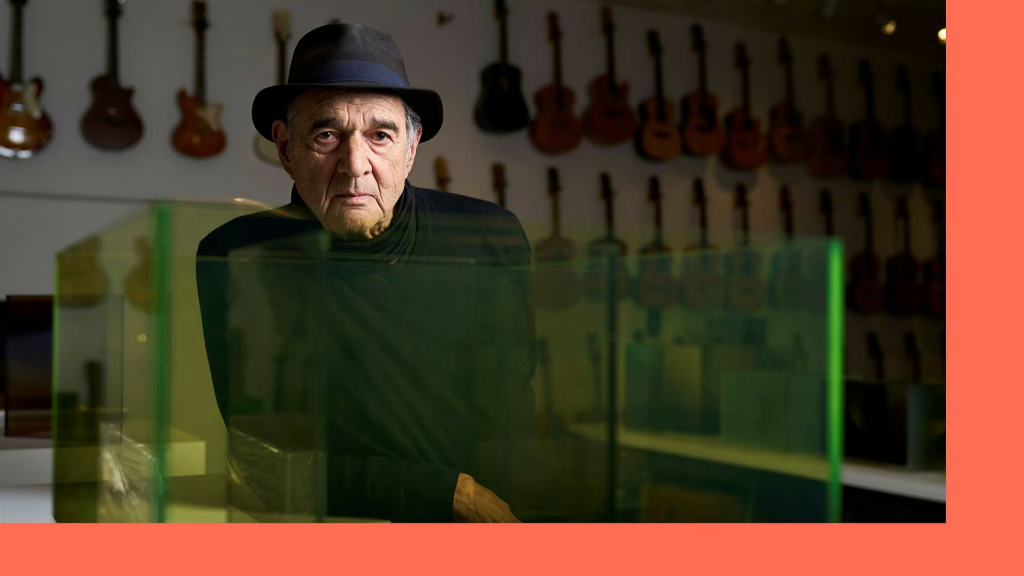

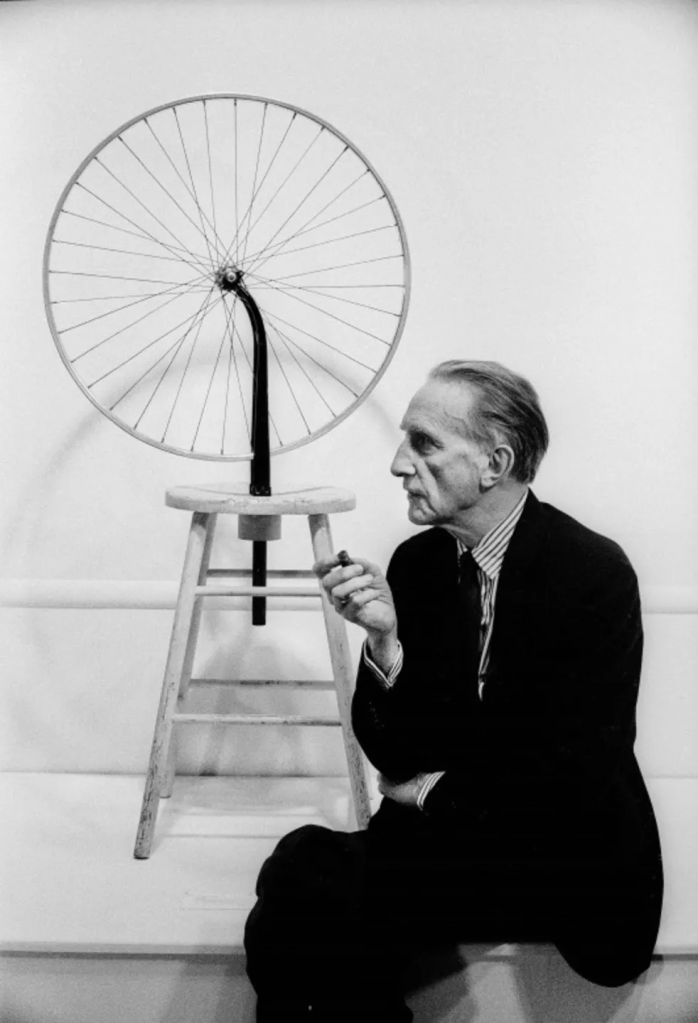

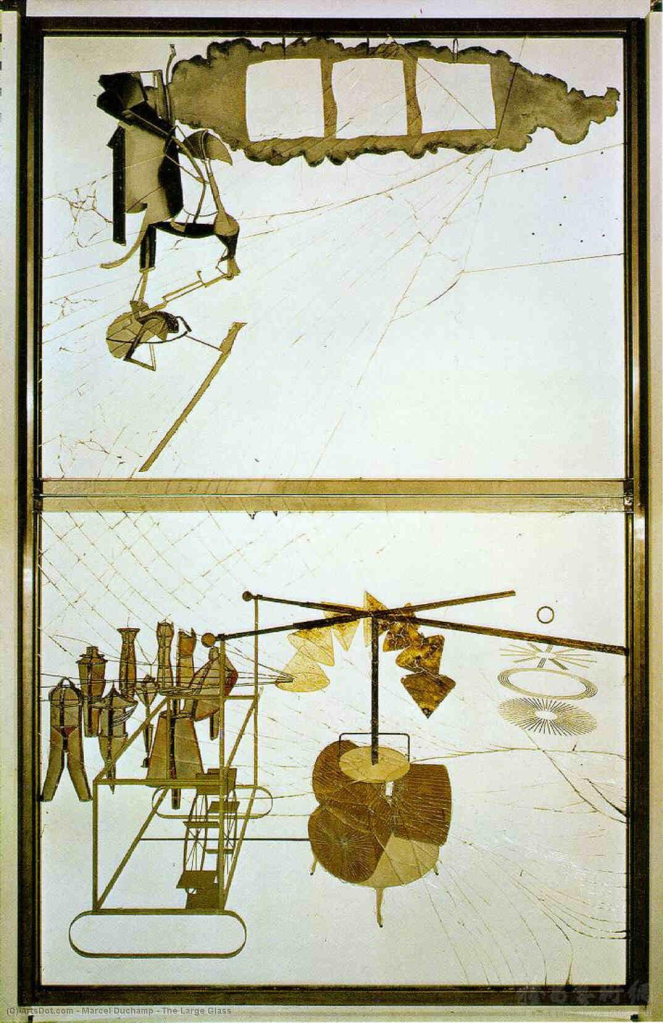

An unusual connection between art and chess is the life of Marcel Duchamp, who in 1923 almost fully suspended his artistic career to focus on chess.

The earliest known reference to chess in a European text is a Medieval Latin poem, Versus de scachis.

The oldest manuscript containing this poem has been given the estimated date of 997.

Other early examples include miniatures accompanying books.

Some of them have high artistic value.

Perhaps the best known example is the 13th-century Libro de los juegos.

The book contains 151 illustrations, and while most of them are centered on the board, showing problems, the players and architectural settings are different in each picture.

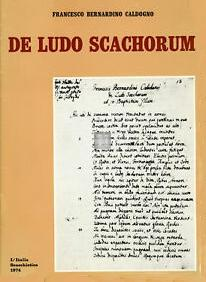

The pieces illustrating chess problems in Luca Pacioli’s Latin manuscript De ludo scacchorum (On the Game of Chess) (1500), described as “futuristic” even by today’s standards, may have been designed by Leonardo da Vinci.

After chess became gradually more popular in Europe in the 15th and 16th centuries, especially in Spain and Italy, many artists began writing poems using chess as a theme.

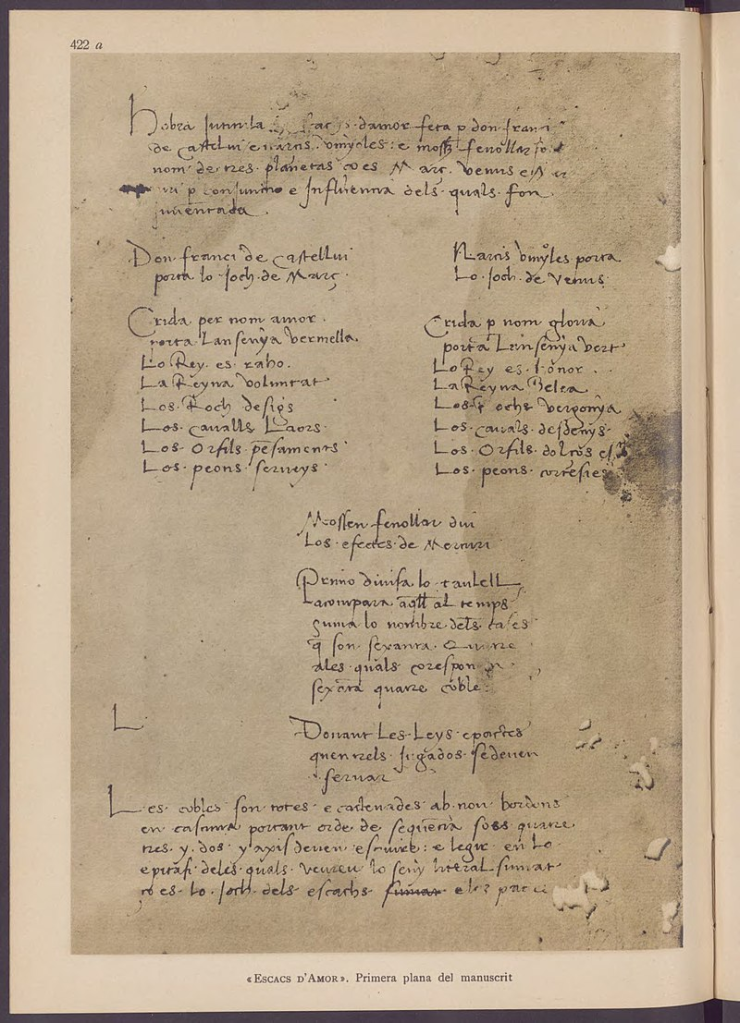

Scachs d’amor (Chess of love), written by an unknown Catalan artist in the end of the 15th century, describes a game between Mars and Venus, using chess as an allegory of love.

The story also serves as a pretence to describe the rules of the game.

De ludo scacchorum by Francesco Bernardino Caldogno, also created at that time, is a collection of gameplay advice, presented in poetic fashion.

One of the most influential works of chess-related art is Marco Girolamo Vida’s Scaccia ludus (1527), centered on a game played between Apollo and Mercury on Mount Olympus.

It is said that, because of its high artistry, the poem made a great impression on anyone who read it, including Desiderius Erasmus.

It also directly inspired at least two other works.

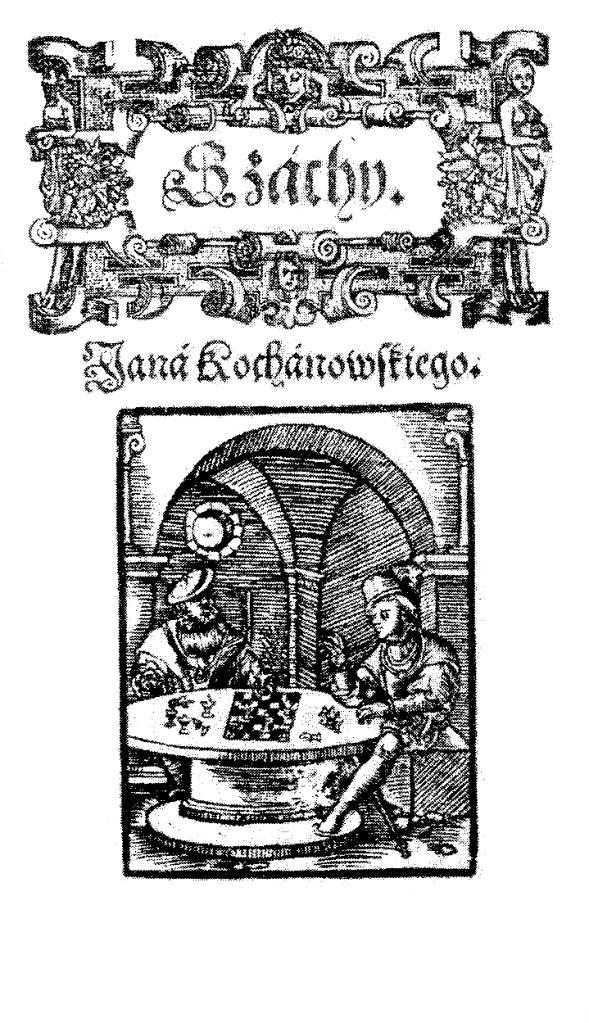

The first is Jan Kochanowski’s poem Chess (1565), which describes the game as a battle between two armies.

The second is William Jones’ Caissa, or the game of chess (1772), popularised the pseudo-ancient Greek dryad Caissa to be the “goddess of chess“.

Since the 19th century, artists have been creating novels and – since the 20th century – films related to chess.

In the 20th century, artists created many works related to the game, sometimes taking their inspiration from the life of famous players or well-known games.

Significant works where chess plays a key role:

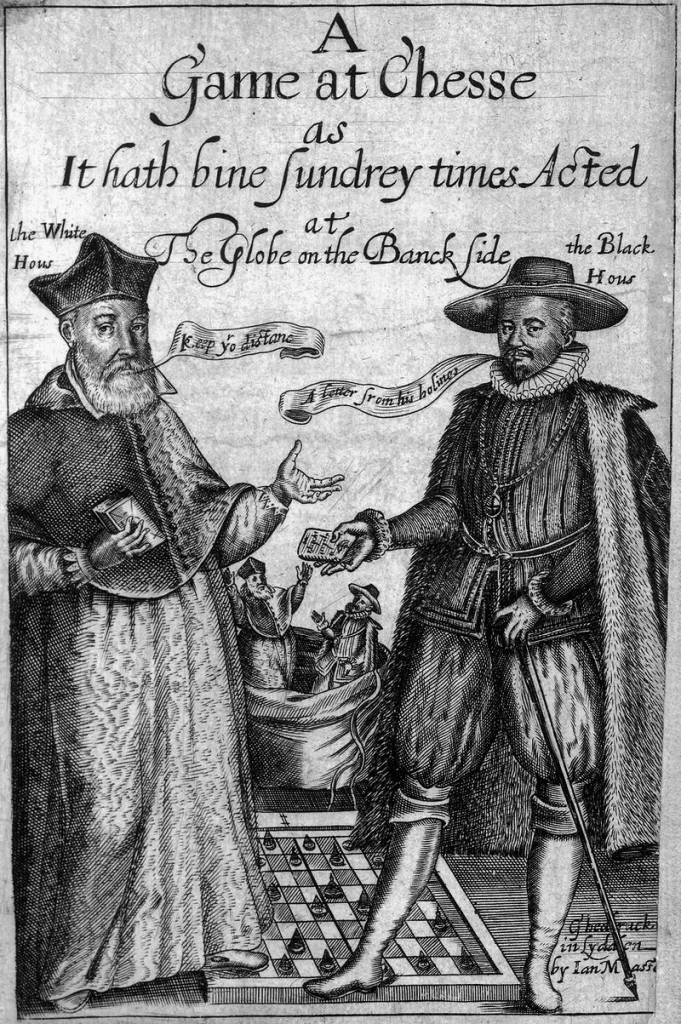

- Thomas Middleton’s A Game at Chess

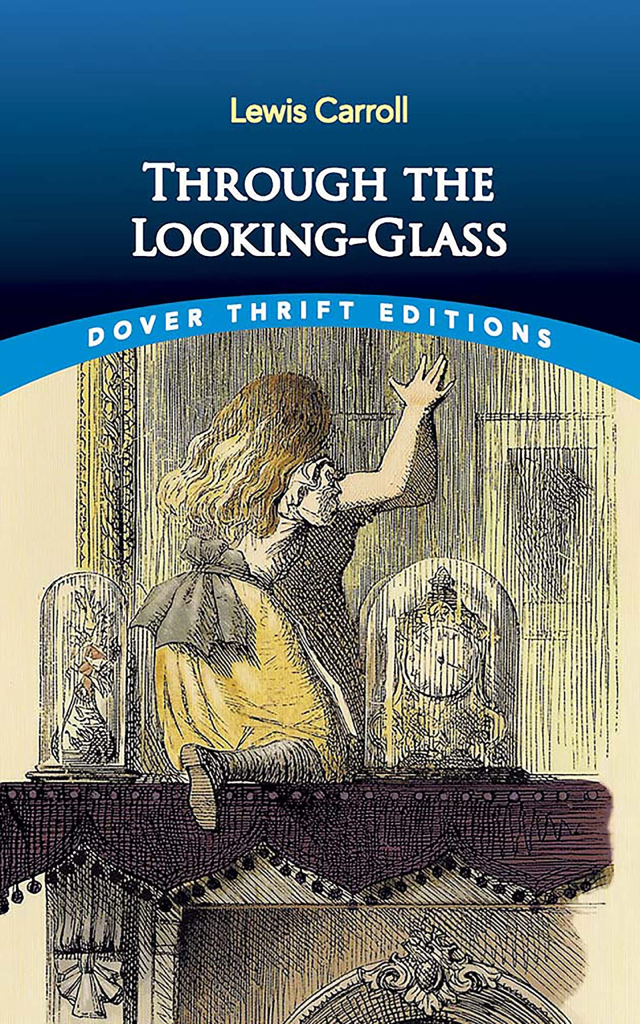

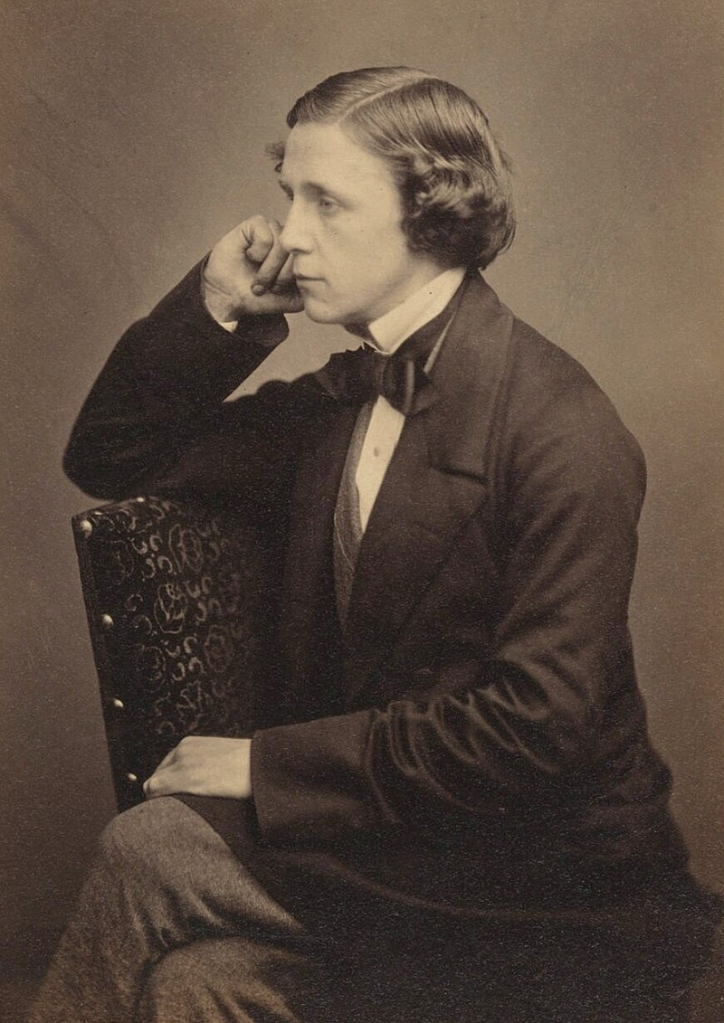

- Through the Looking Glass by Lewis Carroll

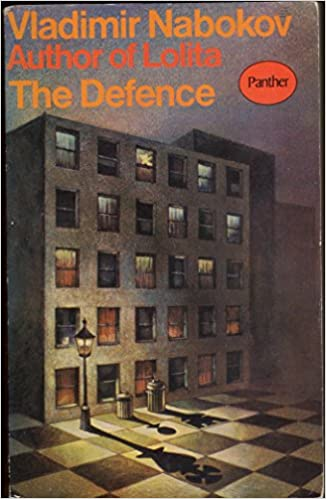

- Vladimir Nabokov’s The Defense

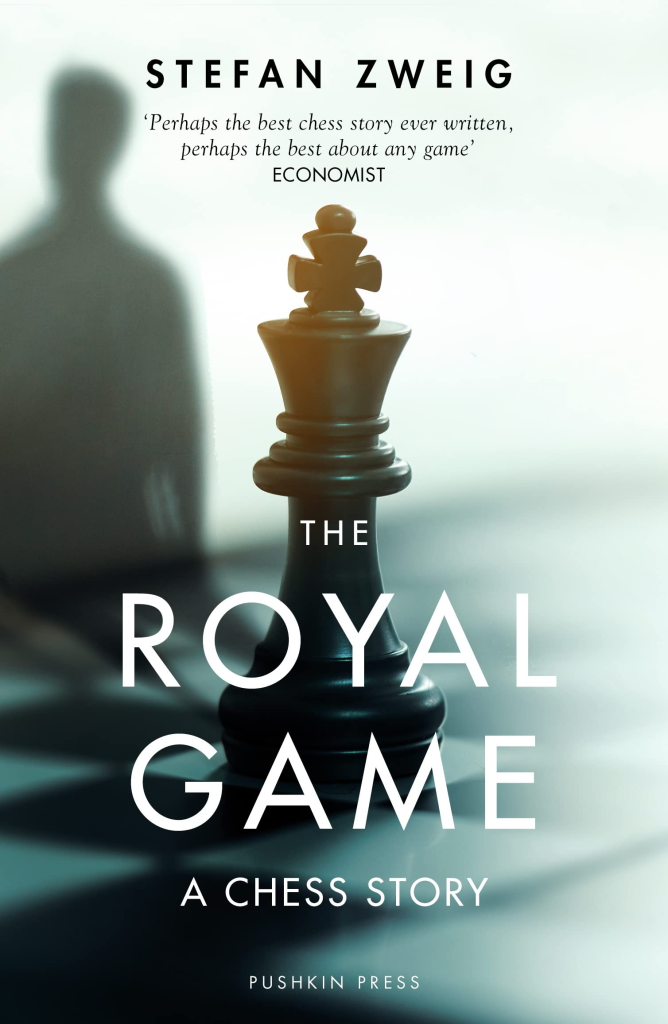

- The Royal Game by Stefan Zweig

- Poul Anderson’s The Immortal Game

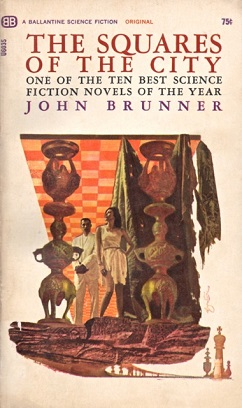

- John Brunner’s The Squares of the City

- Waldemar Lysiak’s The Chess Player

- Kurt Vonnegut’s All the King’s Horses

- Ian Fleming’s From Russia with Love

- Lionel Fanthorpe’s Forbidden Planet

- Italo Calvino’s Invisible Cities

- Ellen Raskin’s The Westing Game

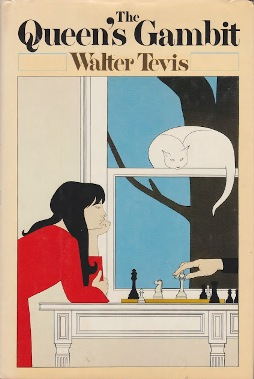

- Walter Tevis’ The Queen’s Gambit

- Fernando Arrabal’s The Tower Struck by Lightning

- George R.R. Martin’s Unsound Variations

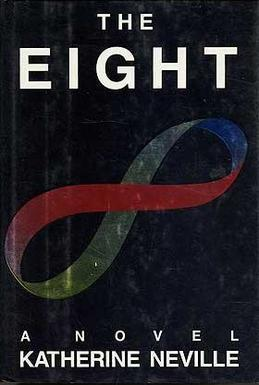

- Katherine Neville’s The Eight

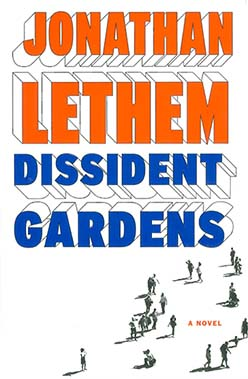

- Jonathan Lethen’s Dissident Gardens

- Ronan Bennett’s Zugzwang

- Roger Zelazny’s Unicorn Variation

- Samuel Beckett’s Endgame

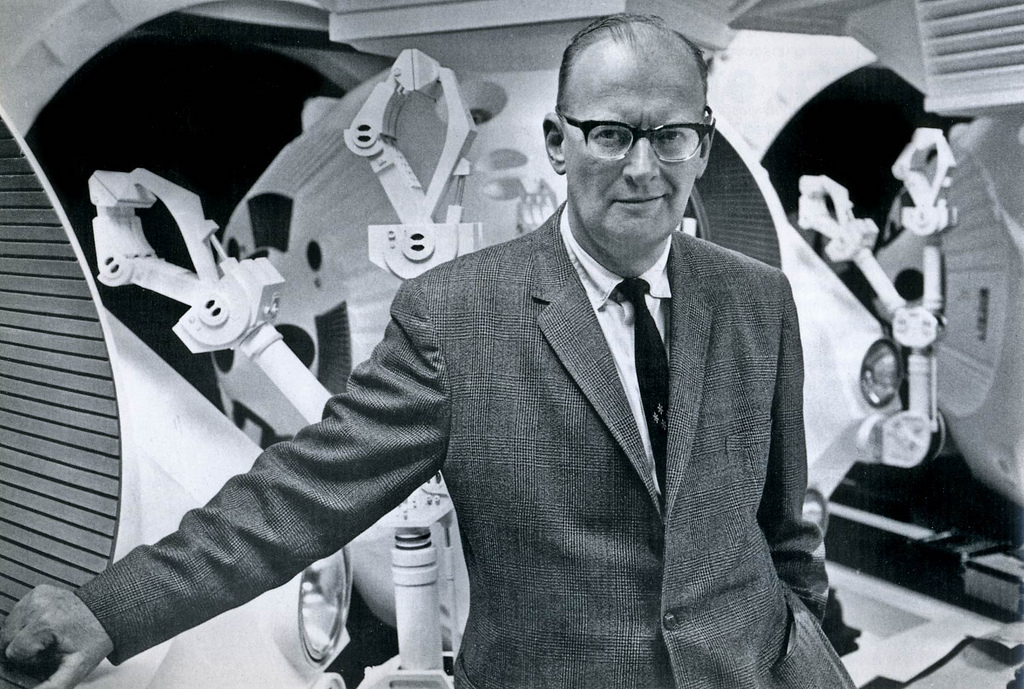

- Arthur C. Clarke’s Quarantine

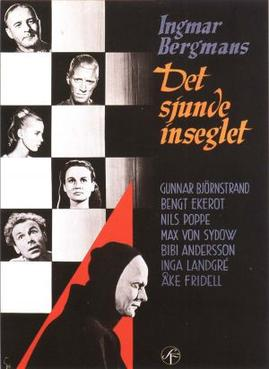

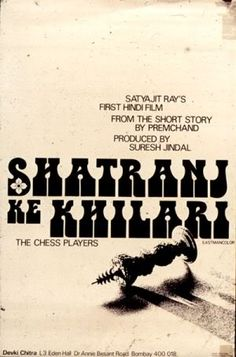

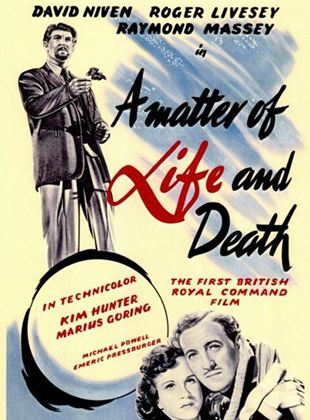

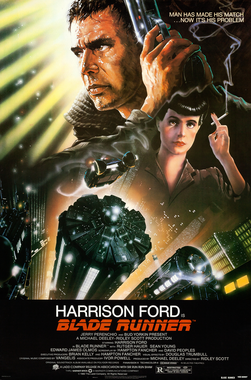

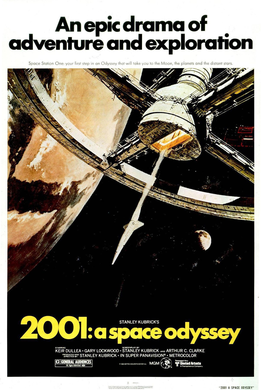

Chess has also featured in film classics such as:

- Ingmar Bergman’s The Seventh Seal

- Satyajit Ray’s The Chess Players

- Powell and Pressburger’s A Matter of Life and Death

- Blade Runner

- 2001: A Space Odyssey

- Knight Moves

- Fresh

- Geri’s Game

- The Shawshank Redemption

- X-Men movie franchise

- The Luzhin Defence

- Knights of the South Bronx

- Life of a King

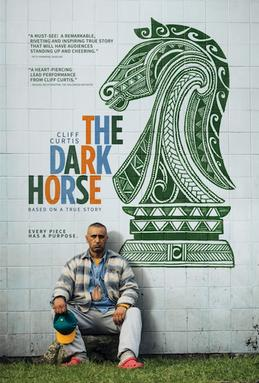

- The Dark Horse

- Queen to Play

Chess is also present in contemporary popular culture.

For example, the characters in Star Trek play a futuristic version of the game called “Federation tridimensional chess“.

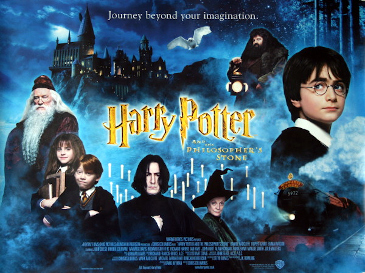

“Wizard’s chess” is played in J.K. Rowling’s Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone.

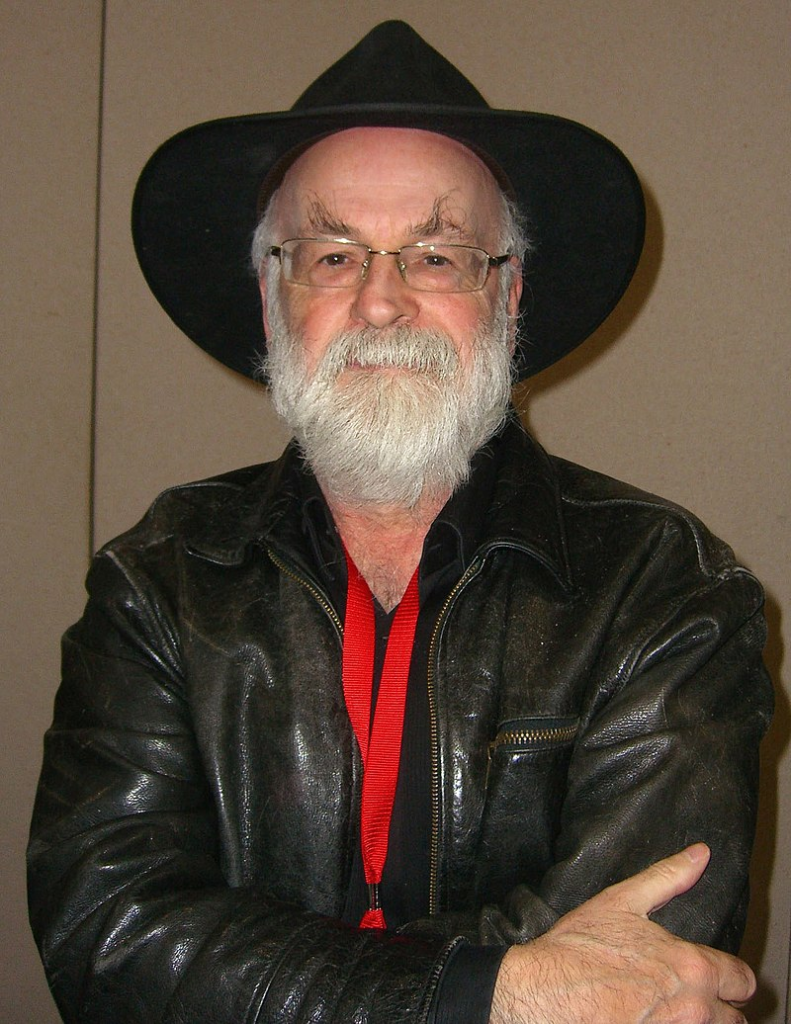

“Stealth chess” is played in Terry Pratchett’s Discworld series.

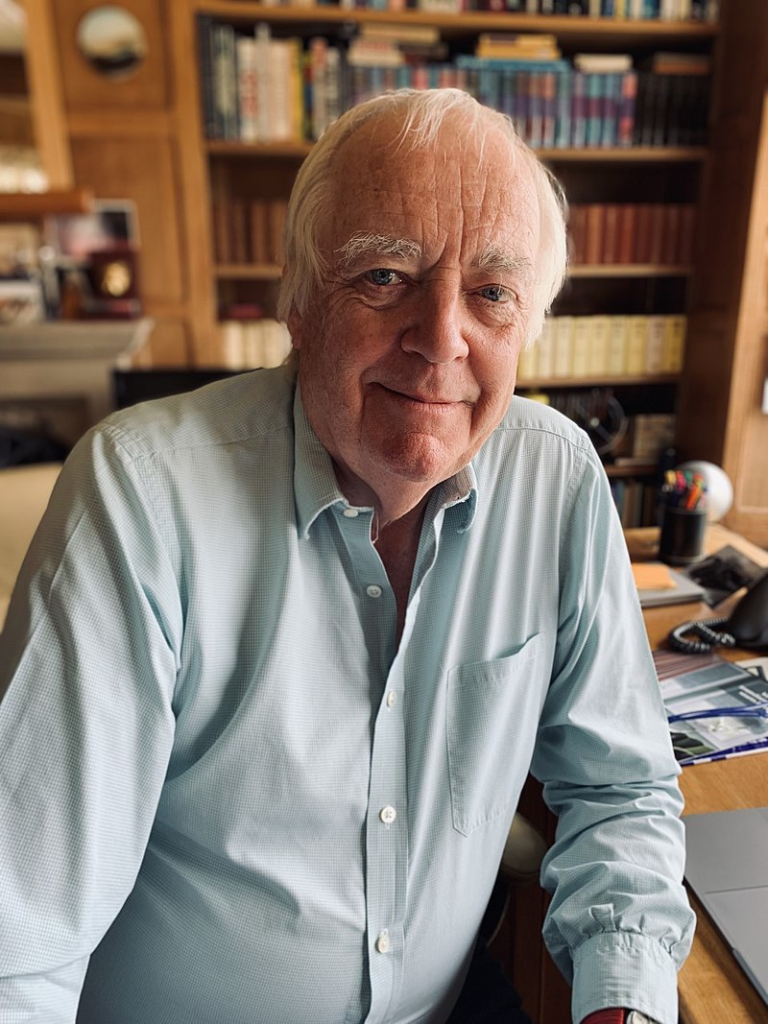

The musical Chess (with its pop hit “One Night in Bangkok“) was loosely based on the life of chess Grandmaster Bobby Fischer.

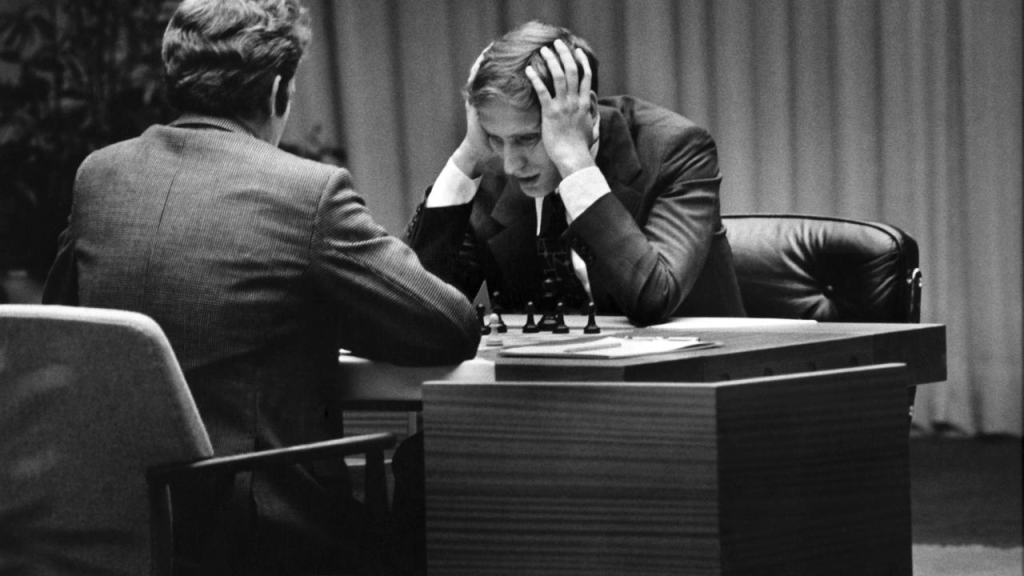

(Robert James Fischer (1943 – 2008) was an American chess grandmaster and the 11th World Chess Champion.

A chess prodigy, at age 14 he won the 1958 US Championship.

In 1964, he won the same tournament with a perfect score (11 wins).

Qualifying for the 1972 World Championship, Fischer swept matches with Mark Taimanov and Bent Larsen by 6–0 scores.

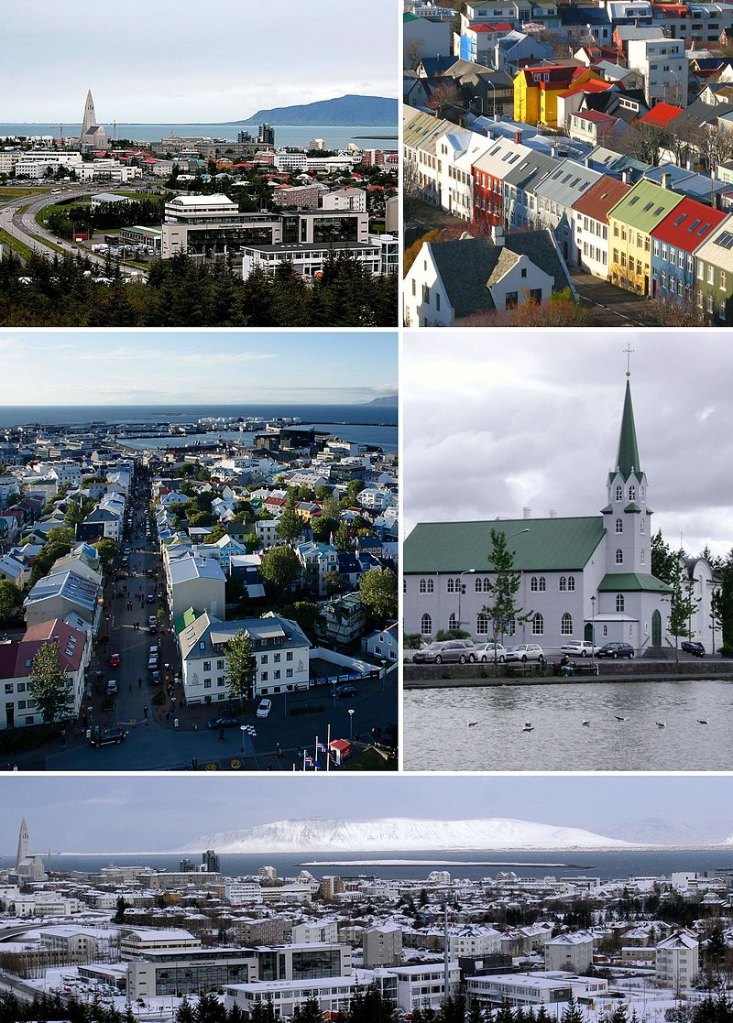

After another qualifying match against Tigran Petrosian, Fischer won the title match against Boris Spassky of the USSR, in Reykjavik, Iceland.

Publicized as a Cold War confrontation between the US and USSR, the match attracted more worldwide interest than any chess championship before or since.

In 1975, Fischer refused to defend his title when an agreement could not be reached with FIDE, chess’s international governing body, over the match conditions.

As a result, the Soviet challenger Anatoly Karpov was named World Champion by default.

Fischer subsequently disappeared from the public eye, though occasional reports of erratic behavior emerged.

In 1992, he reemerged to win an unofficial rematch against Spassky.

It was held in Yugoslavia, which was under a United Nations embargo at the time.

His participation led to a conflict with the US government, which warned Fischer that his participation in the match would violate an executive order imposing US sanctions on Yugoslavia.

The US government ultimately issued a warrant for his arrest.

After that, Fischer lived as an émigré.

In 2004, he was arrested in Japan and held for several months for using a passport that the US government had revoked.

Eventually, he was granted an Icelandic passport and citizenship by a special act of the Icelandic Althing, allowing him to live there until his death in 2008.

Fischer made numerous lasting contributions to chess.

His book My 60 Memorable Games, published in 1969, is regarded as essential reading in chess literature.

In the 1990s, he patented a modified chess timing system that added a time increment after each move, now a standard practice in top tournament and match play.

He also invented Fischer random chess, also known as Chess960, a chess variant in which the initial position of the pieces is randomized to one of 960 possible positions.

Fischer made numerous antisemitic statements and denied the Holocaust.

His antisemitism, professed since at least the 1960s, was a major theme in his public and private remarks.

There has been widespread comment and speculation concerning his psychological condition based on his extreme views and unusual behavior.

The 1993 film Searching for Bobby Fischer uses Fischer’s name in the title even though the film and book are about the life of chess prodigy Joshua Waitzkin whose father wrote the book.

Outside of the United States, it was released as Innocent Moves.

The title refers to the search for Fischer’s successor after his disappearance from competitive chess, since Waitzkin’s father feels that his son could be that successor.

Fischer never saw the film and complained that it invaded his privacy by using his name without his permission.

Fischer never received any compensation from the film, calling it “a monumental swindle“.

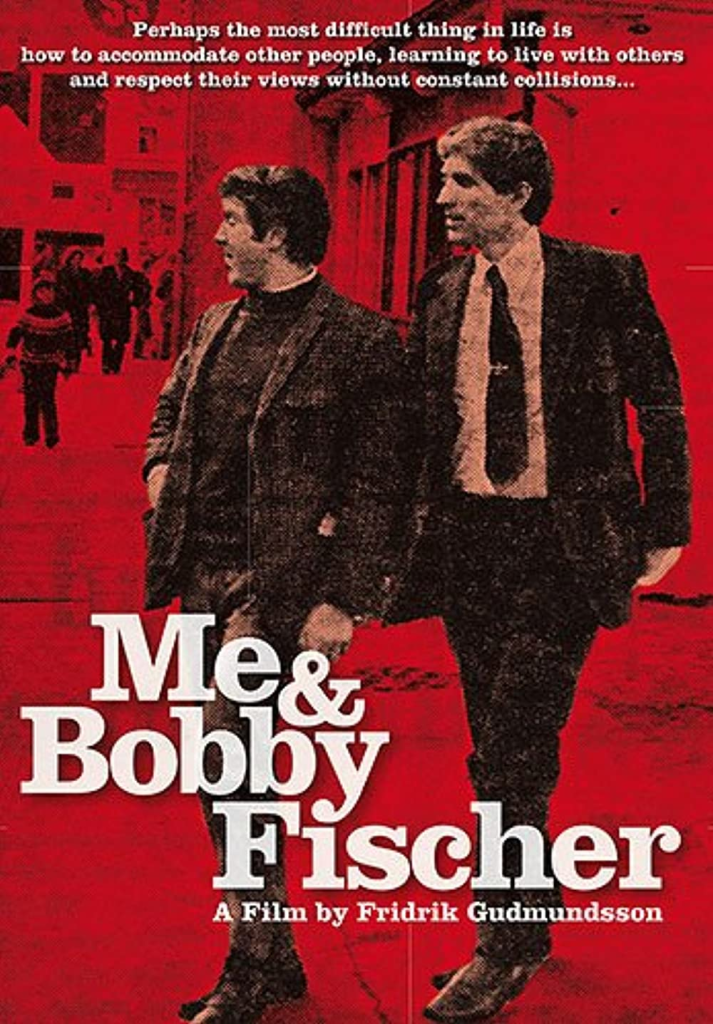

In April 2009, the documentary Me and Bobby Fischer, about Fischer’s last years as his old friend Saemundur Palsson gets him out of jail in Japan and helps him settle in Iceland, was premiered in Iceland.

In October 2009, the biographical film Bobby Fischer Live was released, with Damien Chapa directing and starring as Fischer.

In 2011, documentary filmmaker Liz Garbus released Bobby Fischer Against the World, which explores the life of Fischer, with interviews from Grandmasters Garry Kasparov, Anthony Saidy, and others.

In 2015, the American biographical film Pawn Sacrifice was released, starring Tobey Maguire as Fischer.)

As aforementioned, one unusual connection between art and chess is the life of Marcel Duchamp, who almost fully suspended his artistic career to focus on chess in 1923.

Which leads me to a strange story…..

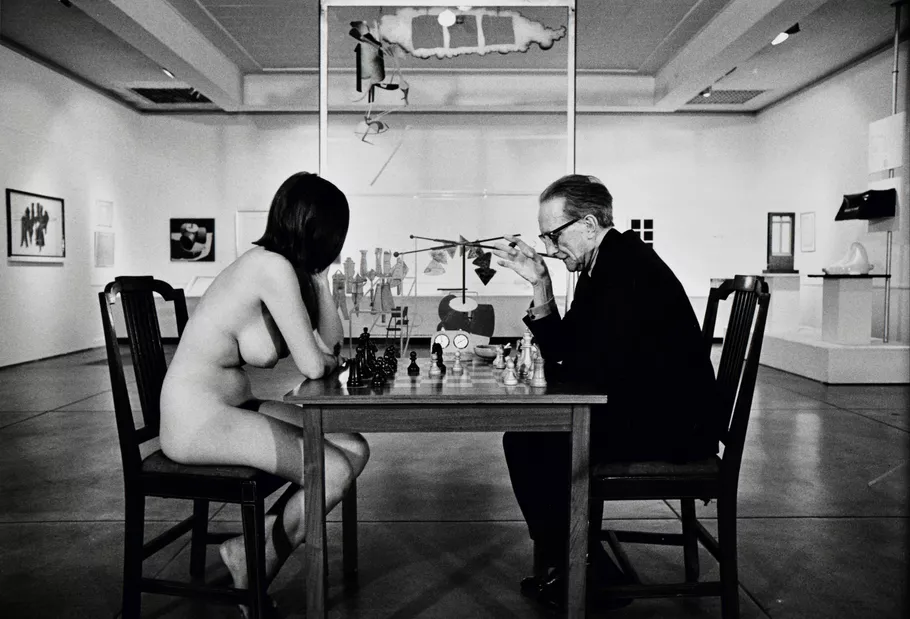

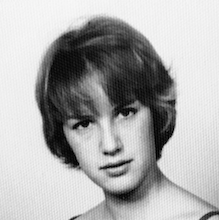

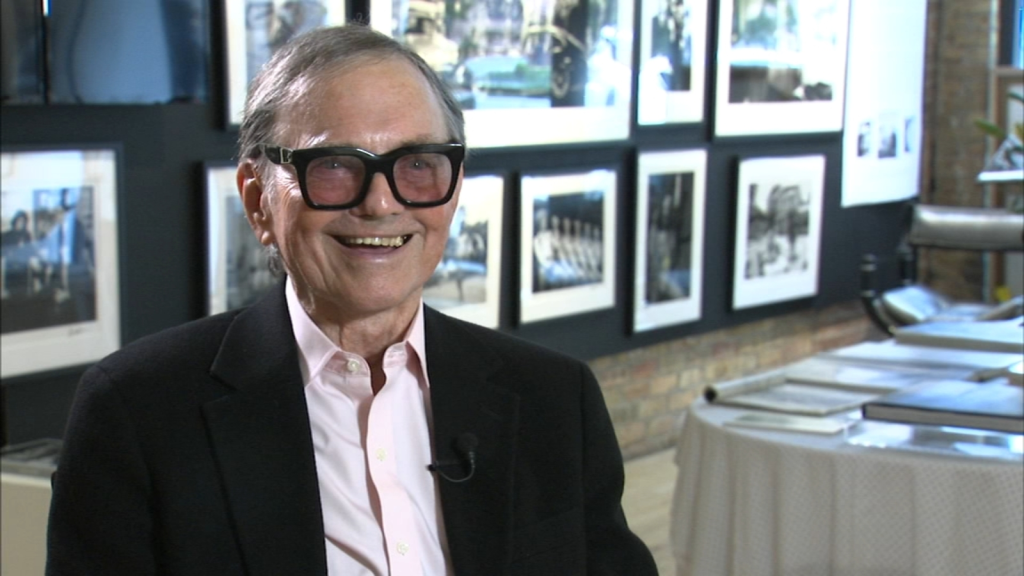

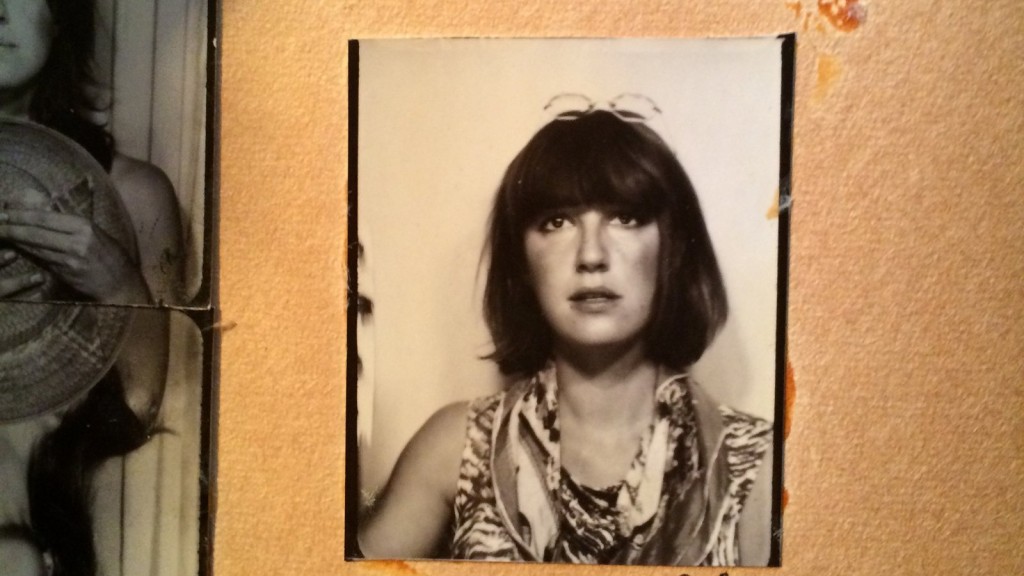

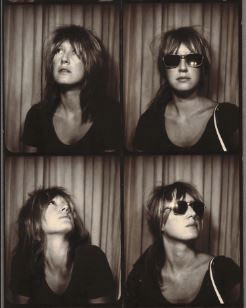

If you knew absolutely nothing about art or literature, Julian Wasser’s photograph of Dadaist Marcel Duchamp and writer Eve Babitz playing chess would still be a knockout.

In the black-and-white picture, made in 1963, a nude, buxom Babitz and a black-suited Duchamp sit at a wood table in an art gallery, manipulating pawns and rooks.

The image’s deadpan humour comes from the subjects’ incongruity, as well as their scrupulous attention to the game —

Neither seems aware of her nakedness.

For fans of Duchamp and Babitz, the photographs capture the meeting of two minds:

- the father of conceptual art, responsible for putting a urinal in a gallery and proclaiming it sculpture

- the writer who captured the glitz of mid-20th-century Los Angeles in sparkling, singular prose

The backstory to Wasser’s photo shoot is both tantalizing gossip and crucial cultural history.

When the pictures were made, Babitz was a 20-year-old student at Los Angeles Community College.

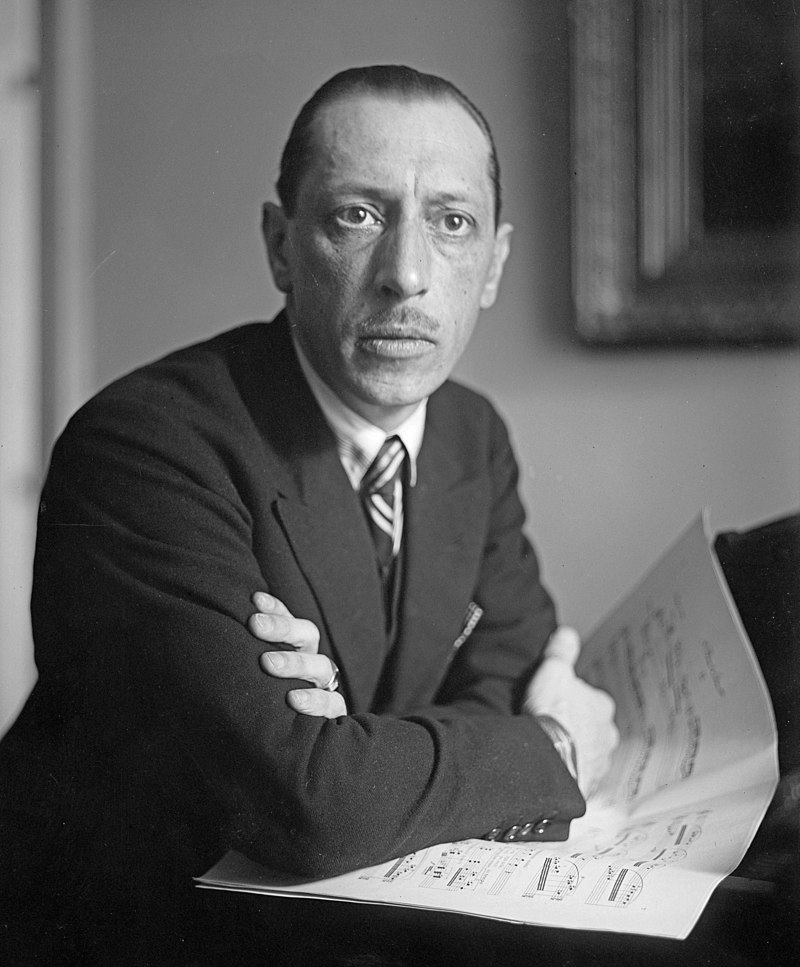

The daughter of a violinist and an artist, and the goddaughter of Russian composer Igor Stravinsky, Babitz was already at ease in a sophisticated, aesthetic milieu.

She integrated herself into L.A.’s slowly burgeoning art scene, partying with Billy Al Bengston, Ed Kienholz, Kenneth Price, and the men who would become integral to the California light and space movement: Larry Bell, Robert Irwin, and Peter Alexander.

Years later, she also became romantically involved with both Ed Ruscha and his brother.

Babitz fully embraced her role as an art groupie.

Through this cast of characters, Babitz met Walter Hopps, a rising art world macher.

He founded Los Angeles’s first major gallery, Ferus, in 1957, then left to become a curator at the Pasadena Art Museum — now the Norton Simon Museum.

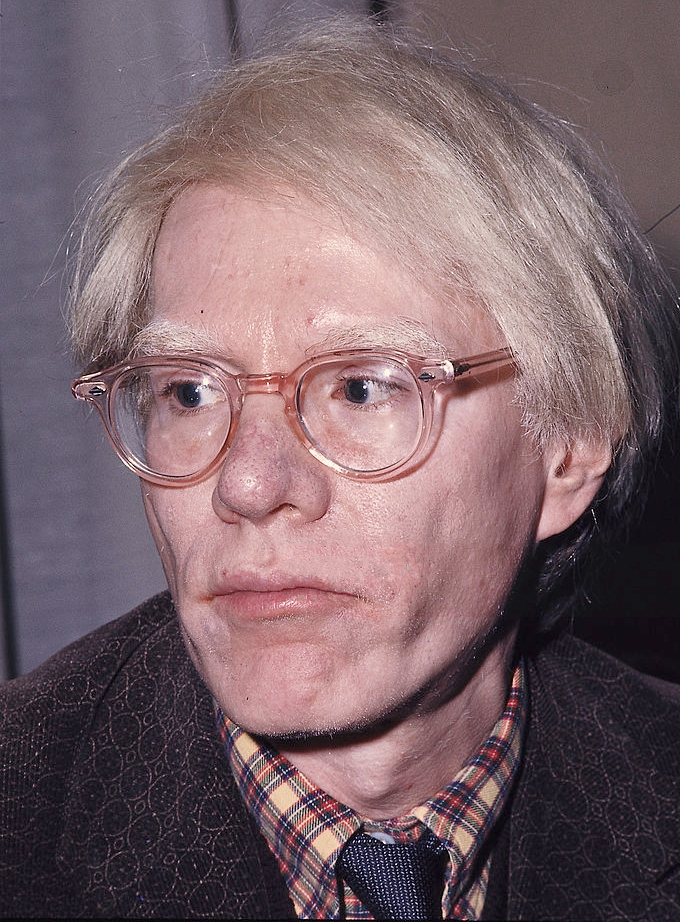

(He left his gallery in good hands, though — his successor, Irving Blum, gave Andy Warhol his first solo show in 1962.)

In the early 1960s, Hopps, who was married to art historian Shirley Nielsen, began an affair with Babitz.

Hopps hadn’t yet turned 30, but he was already instituting a radical, ambitious program at the Museum.

He decided to mount Duchamp’s first American retrospective, and include over 100 artworks.

At the time, Duchamp had long been out of the public eye.

He had gained fame in the 1910s for his concept of the “readymade”— found objects such as a bicycle wheel or snow shovel presented as art.

In 1918, Duchamp took leave of the New York art scene, interrupting his work on The Large Glass.

He went to Buenos Aires, where he remained for nine months and often played chess.

He carved his own chess set from wood with help from a local craftsman who made the knights.

He moved to Paris in 1919 and then back to the United States in 1920.

In 1923, he proclaimed that he was abandoning art making in order to play chess.

Upon his return to Paris, Duchamp was, in essence, no longer a practicing artist.

Instead, his main interest was chess, which he studied for the rest of his life to the exclusion of most other activities.

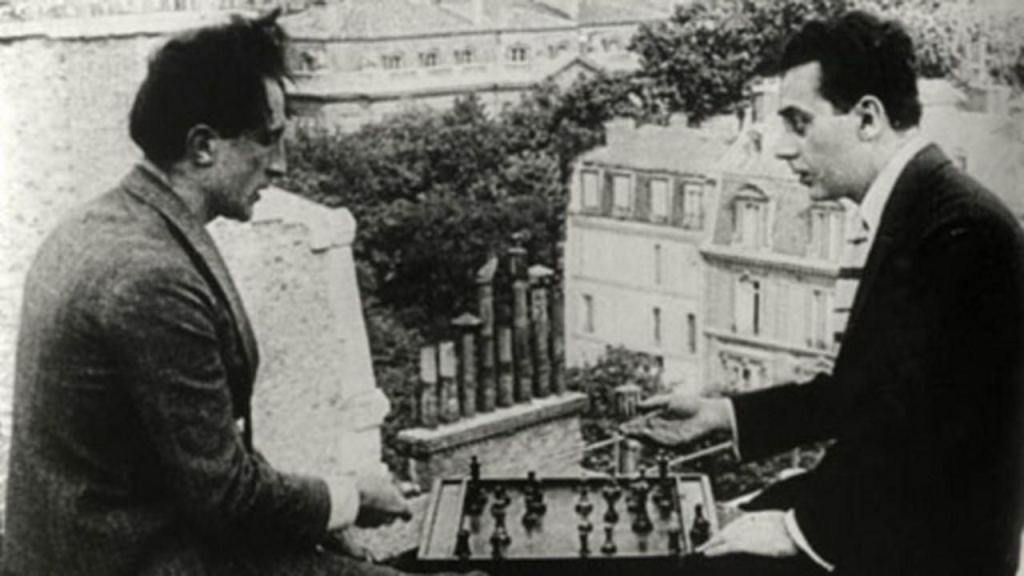

Duchamp is seen, briefly, playing chess with Man Ray in the short film Entr’acte (1924) by René Clair.

He designed the 1925 poster for the Third French Chess Championship, and as a competitor in the event, finished at fifty percent (3–3, with two draws), earning the title of chess master.

During this period his fascination with chess so distressed his first wife that she glued his pieces to the chessboard.

Duchamp continued to play in the French Championships and also in the Chess Olympiads from 1928 to 1933.

Sometime in the early 1930s, Duchamp reached the height of his ability, but realized that he had little chance of winning recognition in top-level chess.

In the following years, his participation in chess tournaments declined, but he discovered correspondence chess and became a chess journalist, writing weekly newspaper columns.

While his contemporaries were achieving spectacular success in the art world by selling their works to high-society collectors, Duchamp observed:

“I am still a victim of chess.

It has all the beauty of art — and much more.

It cannot be commercialized.

Chess is much purer than art in its social position.”

On another occasion, Duchamp elaborated:

“The chess pieces are the block alphabet which shapes thoughts.

These thoughts, although making a visual design on the chessboard, express their beauty abstractly, like a poem.

I have come to the personal conclusion that while all artists are not chess players, all chess players are artists.“

Two decades later, he began work in secret on an enigmatic masterpiece, Étant Donnés (1946 – 1966).

When the show ran, he was — at least publicly — a retired artist in his mid-seventies.

Babitz claims that she didn’t receive an invite to the exhibition’s opening part at the Hotel Green because Hopps’s wife was in town, but even Babitz’s 17-year-old sister, Mirandi, got to attend — and photographer Julian Wasser drove her to the fête.

Seething with envy, Babitz wanted to take revenge on her paramour.

Wasser, who was known for taking nude photographs of young female Angelenos, suggested a titillating form of retribution:

Playing chess at the Museum, in the buff, with Duchamp.

Babitz told the Archives of American Art that the proposition seemed “like the best idea I’d ever heard in my life.

I mean, it was, not only was it vengeance, it was art.”

Lessening her own inhibitions, perhaps, was the fact that Wasser had already shot her naked, at her own command:

In the pre-iPhone era, she had requested and received sexy snapshots to share with men.

Wasser coordinated the photo shoot without alerting either the museum or Duchamp about his intentions.

Babitz’s performance took place before the museum opened, so her audience was the teamster staff “marching back and forth with big pieces of art,” as she once explained.

During the game, Babitz and Duchamp discussed her godfather, Stravinsky, and his famous 1910 suite, The Firebird.

Duchamp won their games as Wasser clicked his shutter.

Eventually, Hopps walked into the gallery and was so surprised that his Double Mint gum fell out of his mouth.

According to Babitz, he began returning her calls after the incident.

Wasser showed Babitz the proofs, and she ultimately selected one in which she was turned away from the camera, her face obscured by her bobbed hair.

At first, she wanted to conceal her identity from the public, though she eventually opened up about her participation in the famous photograph.

The choice, as Lili Anolik points out in her Babitz biography, Hollywood’s Eve (2019), gives the picture additional strangeness as it simultaneously depicts shyness and exhibitionism, a plea for both attention and anonymity.

Anolik writes that Babitz “wasn’t just model and muse, passive and pliable, but artist and instigator, wicked and subversive.”

As Babitz told her biographer, “Walter thought he was running the show, and I finally got to run something.”

Throughout the following decades, she published seven books.

Both her fiction and non-fiction glistened with memorable detail about her Hollywood surroundings, passionate love affairs, and colourful friends.

Without help from Wasser’s framing or Duchamp’s fame, Babitz harnessed the power of her sexuality and fearlessness into art that was all her own.

I find myself more saddened than titillated by this story.

Babitz’s talents seem less literary, less imaginative and more scandalous, more rebellious.

She strikes me as a woman whose creativity was reserved to relating the drama in her life which she herself set into motion.

As for Duchamp, I feel Babitz used him and reduced him to the level of a doddering shadow lost in her sexuality on open display .

Duchamp was important in the famous photograph as only a means to an end, her fame and the mockery of all that he was.

Ultimately the very message of her nudity being ignored by both herself and Duchamp conveys to me the very emptiness of her character.

Take away her sexuality and what is left?

What had she to offer but an account of her sexuality?

Chess is a board game played between two players.

Today, chess is one of the world’s most popular games, played by millions of people worldwide.

Chess is an abstract strategy game and involves no hidden information.

It is played on a square chessboard with 64 squares arranged in an eight-by-eight grid.

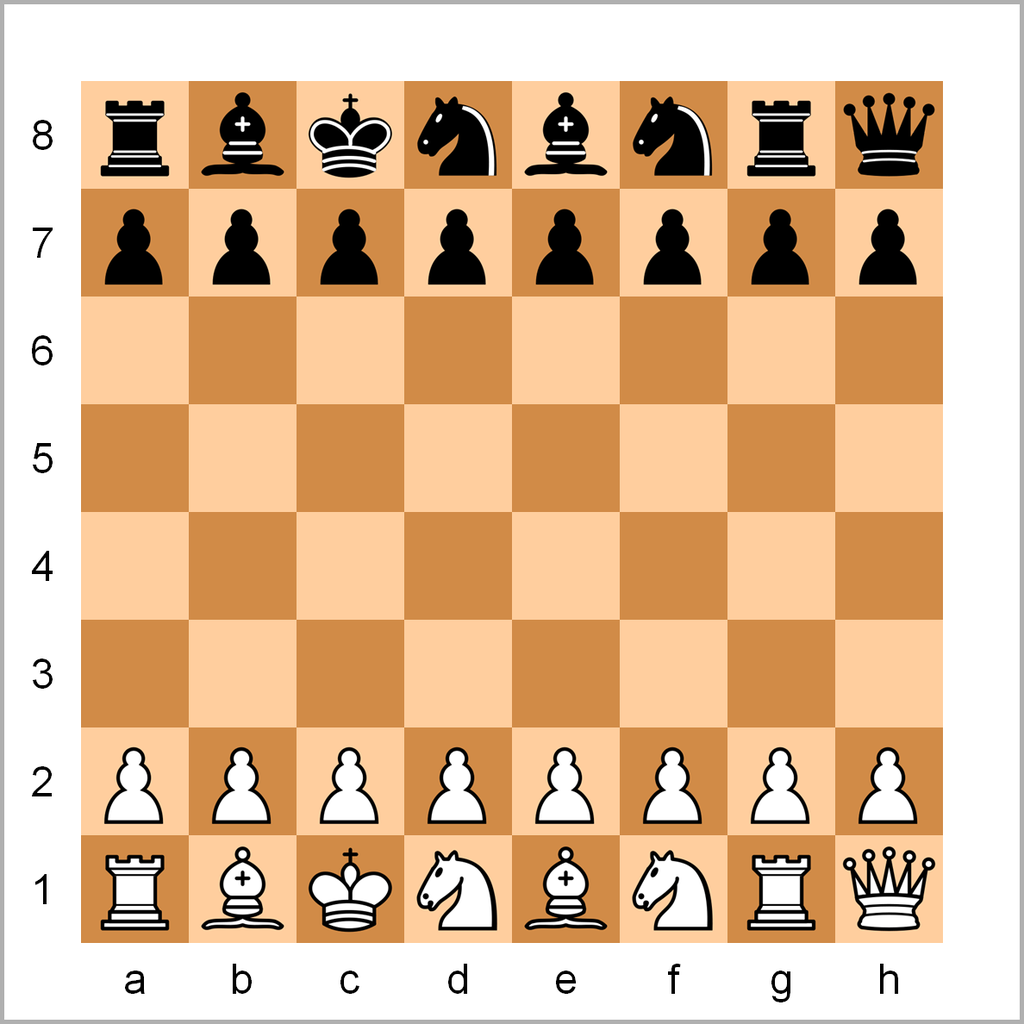

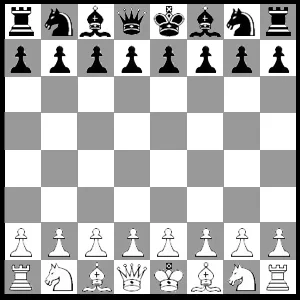

At the start, each player (one controlling the white pieces, the other controlling the black pieces) controls sixteen pieces:

- one king

- one queen

- two rooks

- two bishops

- two knights

- eight pawns

The object of the game is to checkmate the opponent’s king, whereby the king is under immediate attack (in “check“) and there is no way for it to escape.

There are also several ways a game can end in a draw.

Organized chess arose in the 19th century.

Chess competition today is governed internationally by the Fédération Internationale des Échecs (FIDE) (International Chess Federation).

The first universally recognized World Chess Champion, Wilhelm Steinitz, claimed his title in 1886.

Magnus Carlsen is the current World Champion.

A huge body of chess theory has developed since the game’s inception.

Aspects of art are found in chess composition.

Chess in its turn influenced Western culture and art.

It also has connections with other fields such as mathematics, computer science and psychology.

The rules of chess are published by FIDE, chess’s international governing body, in its Handbook.

Chess pieces are divided into two different colored sets.

While the sets may not be literally white and black (e.g. the light set may be a yellowish or off-white color, the dark set may be brown or red), they are always referred to as “white” and “black“.

The players of the sets are referred to as White and Black, respectively.

Chess sets come in a wide variety of styles.

For competition, the Staunton pattern is preferred.

The game is played on a square board of eight rows (ranks) and eight columns (files).

By convention, the 64 squares alternate in color and are referred to as light and dark squares.

Common colors for chessboards are white and brown, or white and dark green.

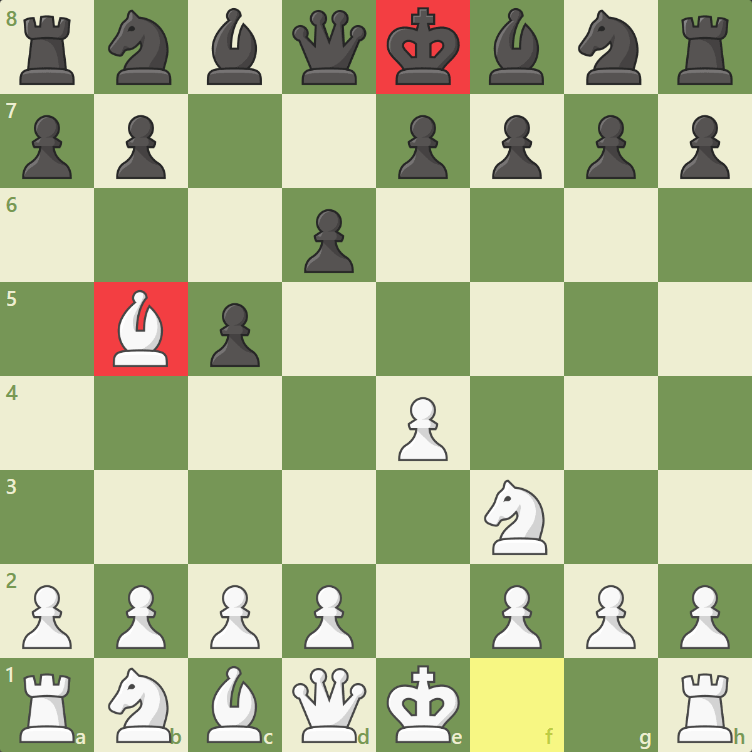

The pieces are set out as shown below:

Thus, on White’s first rank, from left to right, the pieces are placed in the following order:

- rook, knight, bishop, queen, king, bishop, knight, rook.

On the second rank is placed a row of eight pawns.

Black’s position mirrors White’s, with an equivalent piece on the same file.

The board is placed with a light square at the right-hand corner nearest to each player.

The correct positions of the king and queen may be remembered by the phrase “queen on her own colour” ─ i.e. the white queen begins on a light square and the black queen on a dark square.

In competitive games, the piece colors are allocated to players by the organizers.

In informal games, the colours are usually decided randomly, for example by a coin toss, or by one player concealing a white pawn in one hand and a black pawn in the other, and having the opponent choose.

White moves first, after which players alternate turns, moving one piece per turn, except for castling, when two pieces are moved.

A piece is moved to either an unoccupied square or one occupied by an opponent’s piece, which is captured and removed from play.

With the sole exception of en passant, all pieces capture by moving to the square that the opponent’s piece occupies.

Moving is compulsory.

A player may not skip a turn, even when having to move is detrimental.

Each piece has its own way of moving.

All pieces can capture an enemy piece if it is located on a square to which they would be able to move if the square was unoccupied.

- The king moves one square in any direction.

There is also a special move called castling that involves moving the king and a rook.

The king is the most valuable piece — attacks on the king must be immediately countered, and if this is impossible, immediate loss of the game ensues.

Once per game, each king can make a move known as castling.

Castling consists of moving the king two squares toward a rook of the same color on the same rank, and then placing the rook on the square that the king crossed.

Castling is permissible if the following conditions are met:

- Neither the king nor the rook has previously moved during the game.

- There are no pieces between the king and the rook.

- The king is not in check and does not pass through or land on any square attacked by an enemy piece.

- Castling is still permitted if the rook is under attack or if the rook crosses an attacked square.

- A rook can move any number of squares along a rank or file, but cannot leap over other pieces. Along with the king, a rook is involved during the king’s castling move.

- A bishop can move any number of squares diagonally, but cannot leap over other pieces.

- A queen combines the power of a rook and bishop and can move any number of squares along a rank, file, or diagonal, but cannot leap over other pieces.

- A knight moves to any of the closest squares that are not on the same rank, file, or diagonal. (Thus the move forms an “L“-shape: two squares vertically and one square horizontally, or two squares horizontally and one square vertically.)

- The knight is the only piece that can leap over other pieces.

- A pawn can move forward to the unoccupied square immediately in front of it on the same file, or on its first move it can advance two squares along the same file, provided both squares are unoccupied (black dots in the diagram).

- A pawn can capture an opponent’s piece on a square diagonally in front of it by moving to that square (black crosses).

- It cannot capture a piece while advancing along the same file.

- A pawn has two special moves: the en passant capture and promotion.

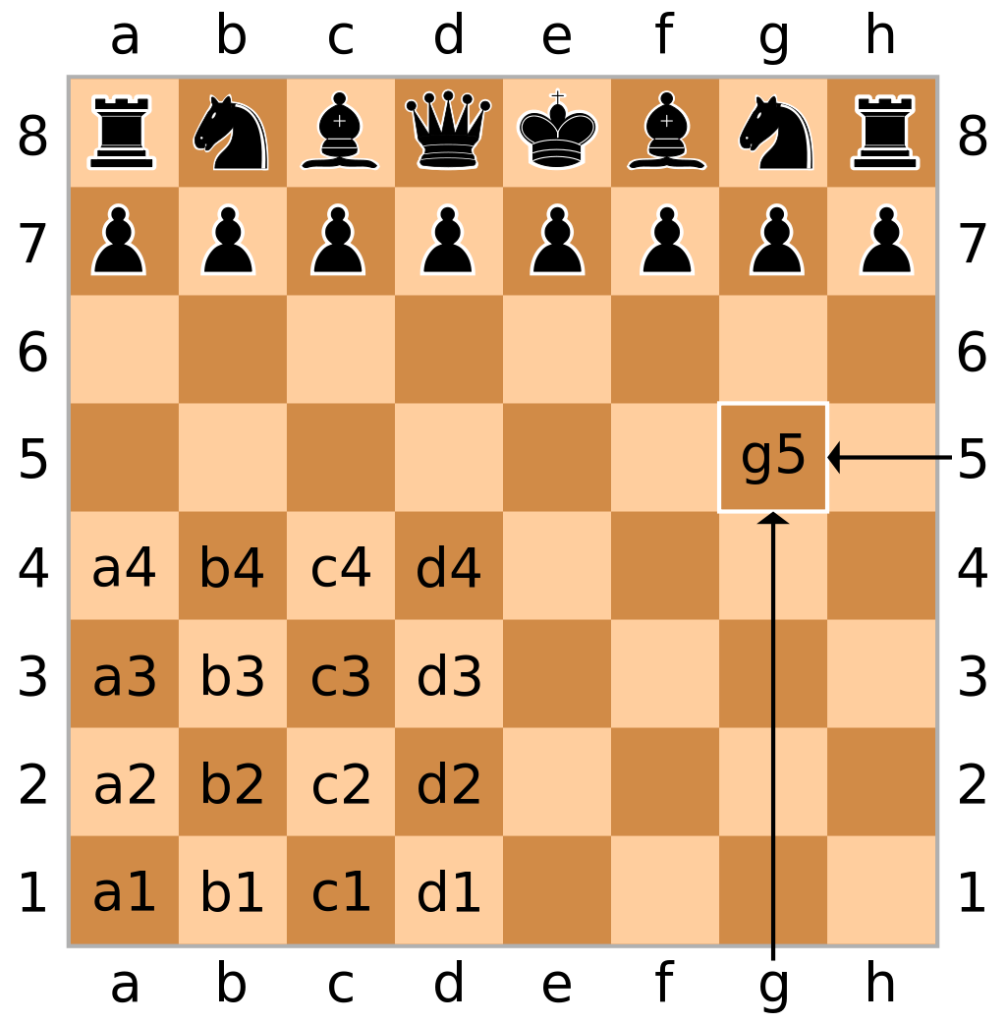

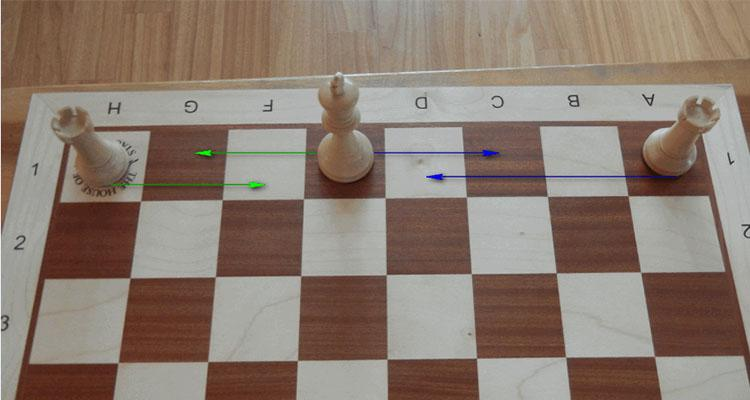

- When a pawn makes a two-step advance from its starting position and there is an opponent’s pawn on a square next to the destination square on an adjacent file, then the opponent’s pawn can capture it en passant (“in passing”), moving to the square the pawn passed over. This can be done only on the turn immediately following the enemy pawn’s two-square advance; otherwise, the right to do so is forfeited. For example, in the animated diagram, the black pawn advances two squares from g7 to g5, and the white pawn on f5 can take it en passant on g6 (but only immediately after the black pawn’s advance).

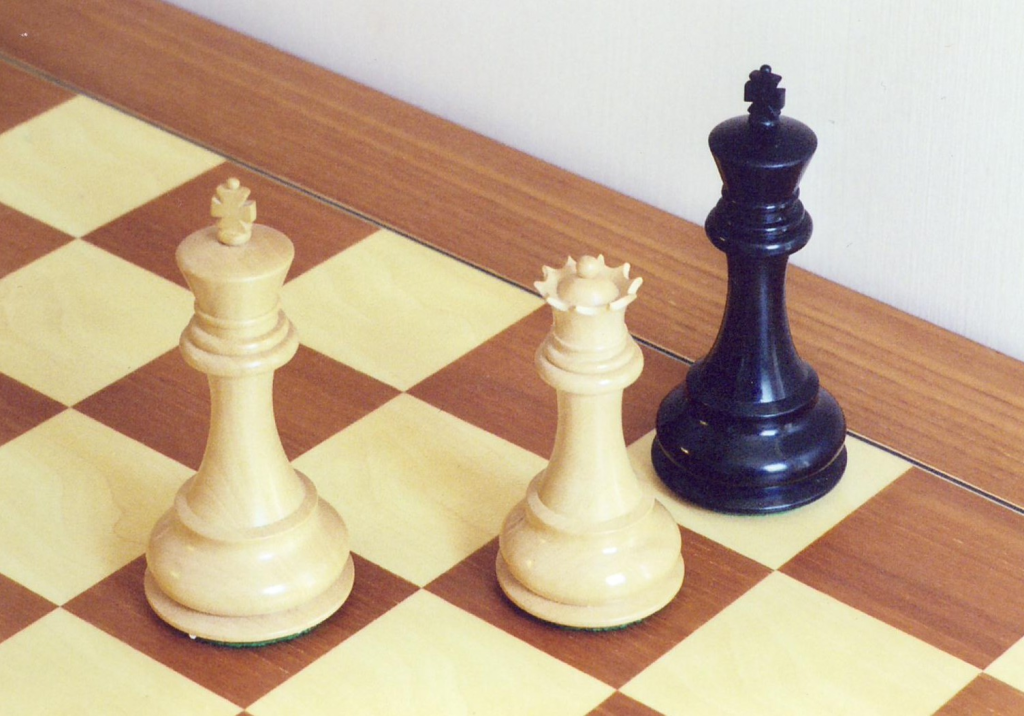

- When a pawn advances to its eighth rank, as part of the move, it is promoted and must be exchanged for the player’s choice of queen, rook, bishop, or knight of the same color. Usually, the pawn is chosen to be promoted to a queen, but in some cases, another piece is chosen. This is called underpromotion. There is no restriction on the piece promoted to, so it is possible to have more pieces of the same type than at the start of the game (e.g., two or more queens). If the required piece is not available (e.g. a second queen) an inverted rook is sometimes used as a substitute, but this is not recognized in FIDE sanctioned games.

When a king is under immediate attack, it is said to be in check.

A move in response to a check is legal only if it results in a position where the king is no longer in check.

This can involve capturing the checking piece.

Interposing a piece between the checking piece and the king (which is possible only if the attacking piece is a queen, rook, or bishop and there is a square between it and the king), or moving the king to a square where it is not under attack.

Castling is not a permissible response to a check.

The object of the game is to checkmate the opponent.

This occurs when the opponent’s king is in check, and there is no legal way to get it out of check.

It is never legal for a player to make a move that puts or leaves the player’s own king in check.

In casual games, it is common to announce “check” when putting the opponent’s king in check, but this is not required by the rules of chess and is not usually done in tournaments.

A game can be won in the following ways:

- Checkmate:

- The king is in check and the player has no legal move.

- Resignation:

- A player may resign, conceding the game to the opponent. Most tournament players consider it good etiquette to resign in a hopeless position.

- Win on time:

- In games with a time control, a player wins if the opponent runs out of time, even if the opponent has a superior position, as long as the player has a theoretical possibility to checkmate the opponent were the game to continue.

- Forfeit:

- A player who cheats, violates the rules, or violates the rules of conduct specified for the particular tournament can be forfeited.

- Occasionally, both players are forfeited.

There are several ways a game can end in a draw:

- Stalemate:

- If the player to move has no legal move, but is not in check, the position is a stalemate, and the game is drawn.

- Dead position:

- If neither player is able to checkmate the other by any legal sequence of moves, the game is drawn. For example, if only the kings are on the board, all other pieces having been captured, checkmate is impossible, and the game is drawn by this rule. On the other hand, if both players still have a knight, there is a highly unlikely yet theoretical possibility of checkmate, so this rule does not apply. The dead position rule supersedes the previous rule which referred to “insufficient material“, extending it to include other positions where checkmate is impossible, such as blocked pawn endings where the pawns cannot be attacked.

- Draw by agreement:

- In tournament chess, draws are most commonly reached by mutual agreement between the players. The correct procedure is to verbally offer the draw, make a move, then start the opponent’s clock. Traditionally, players have been allowed to agree to a draw at any point in the game, occasionally even without playing a move. In recent years, efforts have been made to discourage short draws, for example by forbidding draw offers before move thirty.

- Threefold repetition:

- This most commonly occurs when neither side is able to avoid repeating moves without incurring a disadvantage. In this situation, either player can claim a draw. This requires the players to keep a valid written record of the game so that the claim can be verified by the arbiter if challenged. The three occurrences of the position need not occur on consecutive moves for a claim to be valid. The addition of the fivefold repetition rule in 2014 requires the arbiter to intervene immediately and declare the game a draw after five occurrences of the same position, consecutive or otherwise, without requiring a claim by either player. FIDE rules make no mention of perpetual check. This is merely a specific type of draw by threefold repetition.

- Fifty-move rule:

- If during the previous 50 moves no pawn has been moved and no capture has been made, either player can claim a draw. The addition of the seventy-five-move rule in 2014 requires the arbiter to intervene and immediately declare the game drawn after 75 moves without a pawn move or capture, without requiring a claim by either player. There are several known endgames where it is possible to force a mate, but it requires more than 50 moves before a pawn move or capture is made.

- Draw on time:

- In games with a time control, the game is drawn if a player is out of time and no sequence of legal moves would allow the opponent to checkmate the player.

In competition, chess games are played with a time control.

If a player’s time runs out before the game is completed, the game is automatically lost (provided the opponent has enough pieces left to deliver checkmate).

The duration of a game ranges from long (or “classical“) games, which can take up to seven hours (even longer if adjournments are permitted), to bullet chess (under three minutes per player for the entire game).

Intermediate between these are rapid chess games, lasting between one and two hours per game, a popular time control in amateur weekend tournaments.

Time is controlled using a chess clock that has two displays, one for each player’s remaining time.

Analog chess clocks have been largely replaced by digital clocks, which allow for time controls with increments.

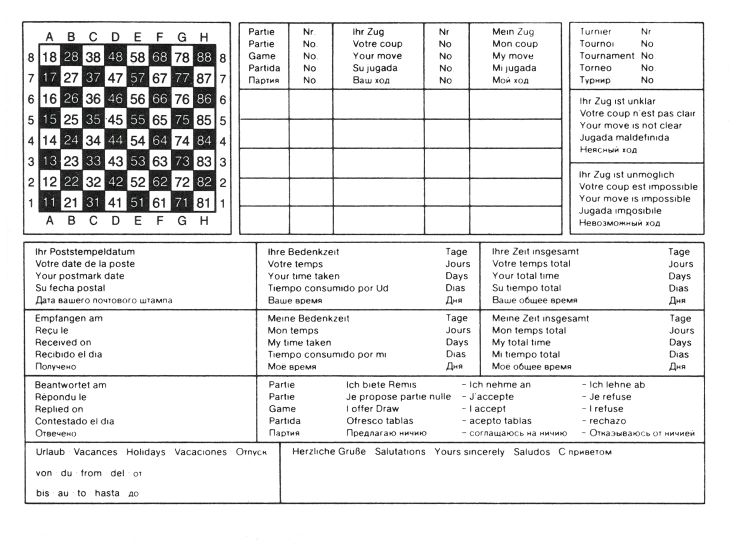

Time controls are also enforced in correspondence chess competitions.

A typical time control is 50 days for every ten moves.

Historically, many different notation systems have been used to record chess moves.

The standard system today is short-form algebraic notation.

In this system, each square is uniquely identified by a set of coordinates, a–h for the files followed by 1–8 for the ranks.

The usual format is:

initial of the piece moved – file of destination square – rank of destination square

The pieces are identified by their initials.

In English, these are K (king), Q (queen), R (rook), B (bishop), and N (knight: N is used to avoid confusion with king).

For example, Qg5 means “queen moves to the g-file, 5th rank” (that is, to the square g5).

Different initials may be used for other languages.

In chess literature, especially that intended for an international audience, the language-specific letters are often replaced by universally recognized piece symbols: for example, ♞c6 in place of Nc6.

This style is known as Figurine Algebraic Notation (FAN)

To resolve ambiguities, an additional letter or number is added to indicate the file or rank from which the piece moved (e.g. Ngf3 means “knight from the g-file moves to the square f3“; R1e2 means “rook on the first rank moves to e2“).

For pawns, no letter initial is used, so e4 means “pawn moves to the square e4“.

If the piece makes a capture, “x” is usually inserted before the destination square.

Thus Bxf3 means “bishop captures on f3“.

When a pawn makes a capture, the file from which the pawn departed is used to identify the pawn making the capture, for example, exd5 (pawn on the e-file captures the piece on d5).

Ranks may be omitted if unambiguous, for example, exd (pawn on the e-file captures a piece somewhere on the d-file).

A minority of publications use “:” to indicate a capture, and some omit the capture symbol altogether.

In its most abbreviated form, exd5 may be rendered simply as ed.

An en passant capture may optionally be marked with the notation “e.p.“

If a pawn moves to its last rank, achieving promotion, the piece chosen is indicated after the move (for example, e1=Q or e1Q).

Castling is indicated by the special notations 0-0 (or O-O) for kingside castling and 0-0-0 (or O-O-O) for queenside castling.

A move that places the opponent’s king in check usually has the notation “+” added.

There are no specific notations for discovered check or double check.

Checkmate can be indicated by “#“.

At the end of the game, “1–0” means White won, “0–1” means Black won, and “½–½” indicates a draw.

Chess moves can be annotated with punctuation marks and other symbols.

For example:

- “!” indicates a good move

- “!!” an excellent move

- “?” a mistake

- “??” a blunder

- “!?” an interesting move that may not be best

- “?!” a dubious move not easily refuted

For example, one variation of a simple trap known as the Scholar’s mate (see animated diagram) can be recorded:

1. e4 e5

2. Qh5?! Nc6

3. Bc4 Nf6??

4. Qxf7#

Chess has an extensive literature.

In 1913, the chess historian H.J.R. Murray estimated the total number of books, magazines, and chess columns in newspapers to be about 5,000.

B.H. Wood estimated the number, as of 1949, to be about 20,000.

David Hooper and Kenneth Whyld write that:

“Since then there has been a steady increase year by year of the number of new chess publications.

No one knows how many have been printed.“

Significant public chess libraries include the John G. White Chess and Checkers Collection at Cleveland Public Library, with over 32,000 chess books and over 6,000 bound volumes of chess periodicals.

The Chess & Draughts collection at the National Library of the Netherlands (The Hague), with about 30,000 books.

There is an extensive scientific literature on chess psychology.

Alfred Binet and others showed that knowledge and verbal, rather than visuospatial, ability lies at the core of expertise.

In his doctoral thesis, Adriaan de Groot showed that chess masters can rapidly perceive the key features of a position.

According to de Groot, this perception, made possible by years of practice and study, is more important than the sheer ability to anticipate moves.

De Groot showed that chess masters can memorize positions shown for a few seconds almost perfectly.

The ability to memorize does not alone account for chess-playing skill, since masters and novices, when faced with random arrangements of chess pieces, had equivalent recall (about six positions in each case).

Rather, it is the ability to recognize patterns, which are then memorized, which distinguished the skilled players from the novices.

When the positions of the pieces were taken from an actual game, the masters had almost total positional recall.

More recent research has focused on chess as mental training:

- the respective roles of knowledge and look-ahead search

- brain imaging studies of chess masters and novices

- blindfold chess

- the role of personality and intelligence in chess skill

- gender differences

- computational models of chess expertise.

The role of practice and talent in the development of chess and other domains of expertise has led to much empirical investigation.

Ericsson and colleagues have argued that deliberate practice is sufficient for reaching high levels of expertise in chess.

Recent research, however, fails to replicate their results and indicates that factors other than practice are also important.

For example, Fernand Gobet and colleagues have shown that stronger players started playing chess at a young age and that experts born in the Northern Hemisphere are more likely to have been born in late winter and early spring.

Compared to the general population, chess players are more likely to be non-right-handed, though they found no correlation between handedness and skill.

A relationship between chess skill and intelligence has long been discussed in scientific literature as well as in popular culture.

Academic studies that investigate the relationship date back at least to 1927.

Although one meta-analysis and most children studies find a positive correlation between general cognitive ability and chess skill, adult studies show mixed results.

One woman, Judit Polgár (generally considered the strongest female chess player ever), was at one time the 8th highest rated chess player in the world.

She is the only woman to have ever been in the top ten of the world’s chess players.

Three women, Maia Chiburdanidze, Polgár, and Hou Yifan, have been ranked in the world’s top 100 players.

Analysis of rating statistics of German players in an article from 2009 by Merim Bilalić, Kieran Smallbone, Peter McLeod, and Fernand Gobet indicated that although the highest-rated men were stronger than the highest-rated women, the difference (usually more than 200 rating points) was largely accounted for by the relatively smaller pool of women players (only one-sixteenth of rated German players were women).

In 2020, psychologist and neuroscientist Wei Ji Ma summarized the state of research on women in chess as “there is currently zero evidence for biological differences in chess ability between the genders” but added “that does not mean that there are certainly no such differences“.

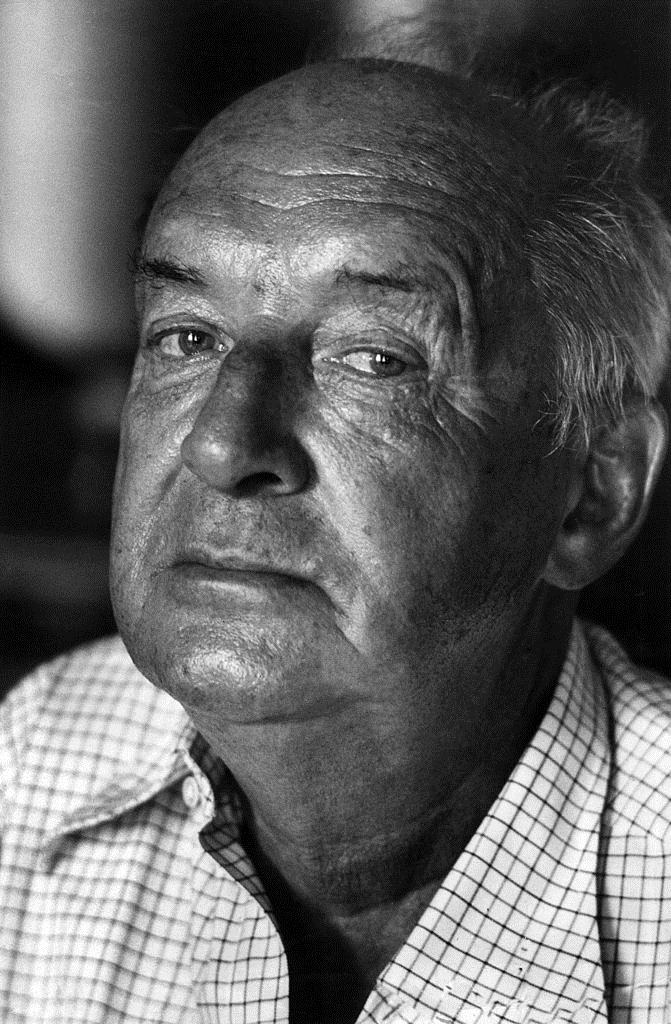

The Queen’s Gambit is a 1983 American novel by Walter Tevis, exploring the life of fictional female chess prodigy Beth Harmon.

A Bildungsroman, or coming-of-age story, it covers themes of adoption, feminism, chess, drug addiction and alcoholism.

The book was adapted for the 2020 Netflix miniseries of the same name.

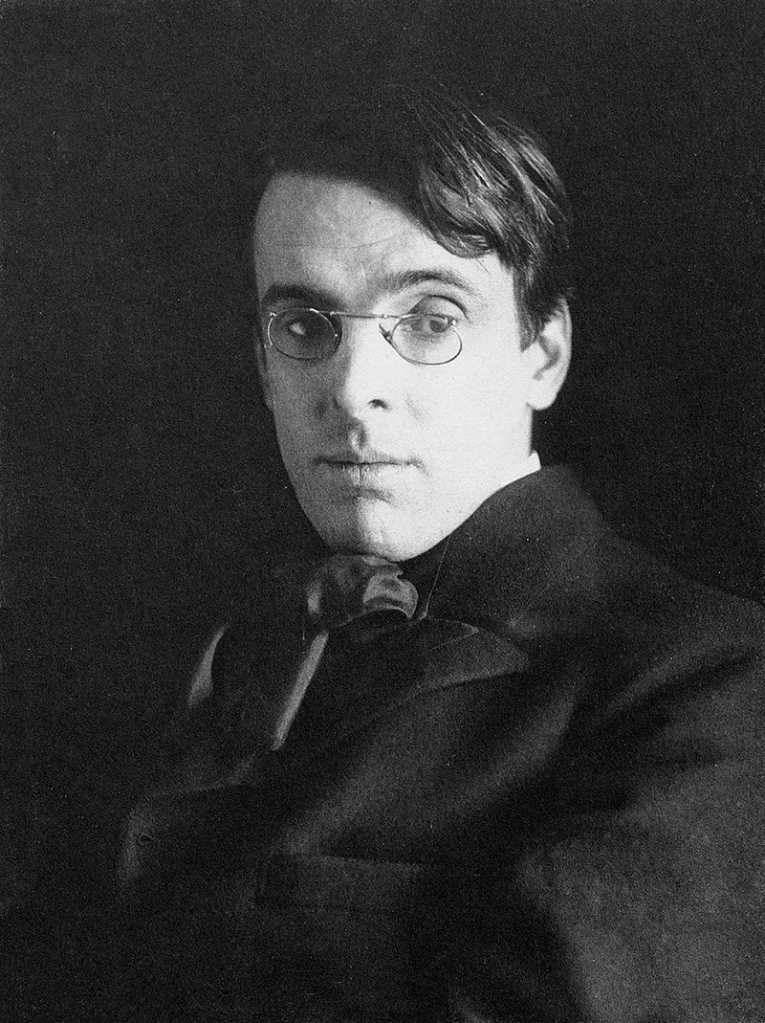

The novel’s epigraph is “The Long-Legged Fly” by W.B. Yeats.

This poem highlights one of the novel’s main concerns: the inner workings of genius in a woman.

Tevis discussed this concern in a 1983 interview, the year before his death.

The Long-Legged Fly

That civilisation may not sink,

Its great battle lost,

Quiet the dog, tether the pony

To a distant post.

Our master Caesar is in the tent

Where the maps are spread,

His eyes fixed upon nothing,

A hand upon his head.

Like a long-legged fly upon the stream

His mind moves upon silence.

That the topless towers be burnt

And men recall that face,

Move most gently if move you must

In this lonely place.

She thinks, part woman, three parts a child,

That nobody looks; her feet

Practise a tinker shuffle

Picked up on the street.

Like a long-legged fly upon the stream

Her mind moves upon silence.

That girls at puberty may find

The first Adam in their thought,

Shut the door of the Pope’s chapel,

Keep those children out.

There on that scaffolding reclines

Michael Angelo.

With no more sound than the mice make

His hand moves to and fro.

Like a long-legged fly upon the stream

His mind moves upon silence.

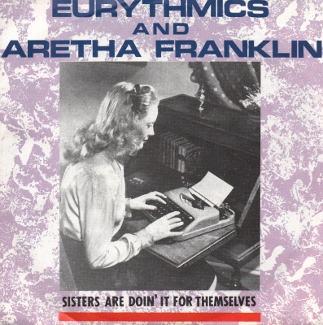

Let me choose my words carefully henceforth:

Life offers the human being two choices: animal existence – a lower order of life – and spiritual existence.

Some women choose the former.

Men and women have the same intellectual potential.

There is no primary difference in intelligence between the sexes, but potential left to stagnate will atrophy.

Some women do not use their mental capacity.

They deliberately let it disintegrate.

Why do some women not make use of their intellectual potential?

For the simple reason they do not need to.

It is not essential for their survival.

“She thinks, part woman, three parts child.”

By the age of 12 at the latest, some women have planned a future for themselves which consists of choosing a man and letting him do all the work.

The moment a woman has made this decision she ceases to develop her mind.

She may, of course, go on to obtain various degrees and diplomas, but these increase her market value in the eyes of men, for men believe that a woman who can recite things by heart must also know and understand them.

And some women do.

But not all women.

Too few women use the time they have gained from labour-saving devices to take an active interest in history, politics or astrophysics, knowledge beyond the status quo of mere survival and propagation of the species.

Instead they take an interest in themselves.

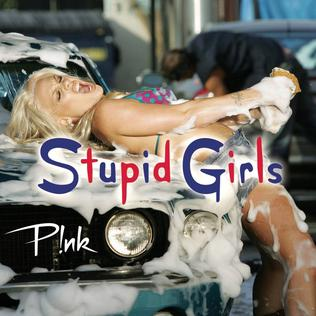

Stupid girl

Stupid girls

Stupid girls

Maybe if I act like that

That guy will call me back

Porno paparazzi girls

I don’t wanna be a stupid girl

Go to Fred Segal, you’ll find them there

Laughing loud, so all the little people stare

Looking for a daddy to pay for the champagne

Droppin’ names

What happened to the dream of a girl president

She’s dancing in the video next to 50 cent

They travel in packs of two and three

With their itsy-bitsy doggies and their teeny-weeny tees

Where, oh where, have the smart people gone?

Oh where, oh where could they be?

Maybe if I act like that

That guy will call me back

Porno paparazzi girls

I don’t wanna be a stupid girl

Baby, if I act like that

Flippin’ my blond hair back

Push up my bra like that

I don’t wanna be a stupid girl

Break it down now

The disease is growing, it’s epidemic

I’m scared that there ain’t a cure

The world believes it, and I’m going crazy

I cannot take anymore

I’m so glad that I’ll never fit in

That will never be me

Outcasts and girls with ambition

That’s what I wanna see (come on)

Disaster’s all around (disaster’s all around)

A world of despair (a world of despair)

Your only concern, “Will it f— up my hair?”

Maybe if I act like that

That guy will call me back

Porno paparazzi girls

I don’t wanna be a stupid girl

Baby, if I act like that

Flippin’ my blond hair back

Push up my bra like that

I don’t wanna be a stupid girl

The feminine claim to beauty is supported by subterfuge, by a trick, to appear as much as a child as possible: appealing eyes, clear and taut skin, a child’s easy laugh, the appearance of helplessness, the need for protection, babbles and exclamations, inane little bursts of commentary, a preservation of a baby look so as to make the world continue to believe in the darling sweetheart girl she once was so as to induce the protective instinct in man to make him take care of her.

Without the longing after intellectual achievements, she concentrates on her external appearance.

So shortsighted, to encourage an ideal of beauty that no woman can hope to maintain beyond the age of 25!

Despite every trick of the cosmetics industry, a case of those who fool being fooled, her actual age will inevitably show through in the end.

Smooth becomes flabby, soft skin turns slack and pallid, the melody of youth becomes shrill, laughter of a lass becomes the bray of an ass.

Too few women make use of their mental processes to develop their own theories.

Too few do independent research in institutes.

Too few read the literature of libraries.

Admire marvellous works of art she might, but she will rarely create, only copy.

Some women lack ambition, desire knowledge or possess the need to prove themselves.

For women have a choice that most men do not – they can develop themselves or instead allow themselves to stagnate.

Some women choose the former, others the latter.

I am not suggesting that women can’t be the equal of men.

I am suggesting that some women, who do have a choice, choose not to be.

The other observation that seems to reoccur time and time again where chess is dealt with in the arts is how depressingly often those who excel at chess seem psychologically “off“.

Sometimes I wonder if only the insane can play chess insanely well.

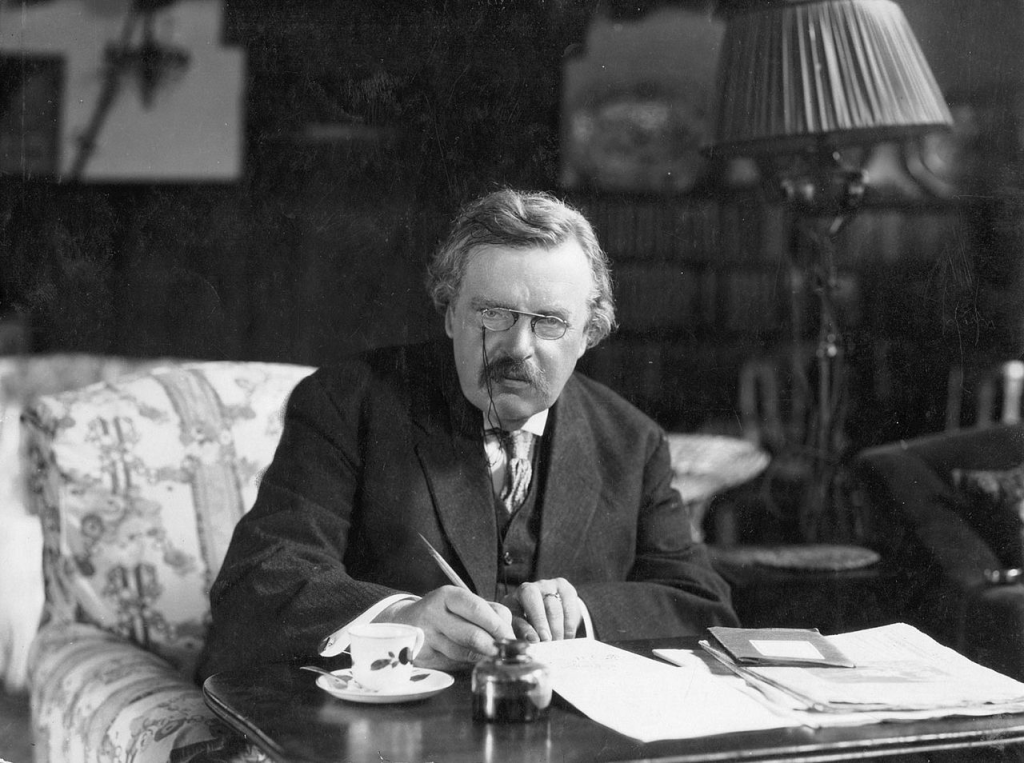

G. K. Chesterton quipped:

“Poets do not go mad, but chess players do.”

Bobby Fischer claimed:

“I give 98% of my mental energy to chess.

Others give only 2%.”

He was not only trumpeting his extraordinary dedication but also signaling how little ground he had left for himself in the real world.

After reaching the summit of his obsession, Fischer found nowhere to go but down into his own paranoia.

But as the writer Andrew Anthony observed, Fischer’s “descent into wild and irrational behavior is far from a unique narrative, particularly in chess.

The history of the game contains many similar trajectories.”

Perhaps no sport is more dangerous in this way than chess, with so many great players losing their way ––and often their minds –– in their obsessive quest to win.

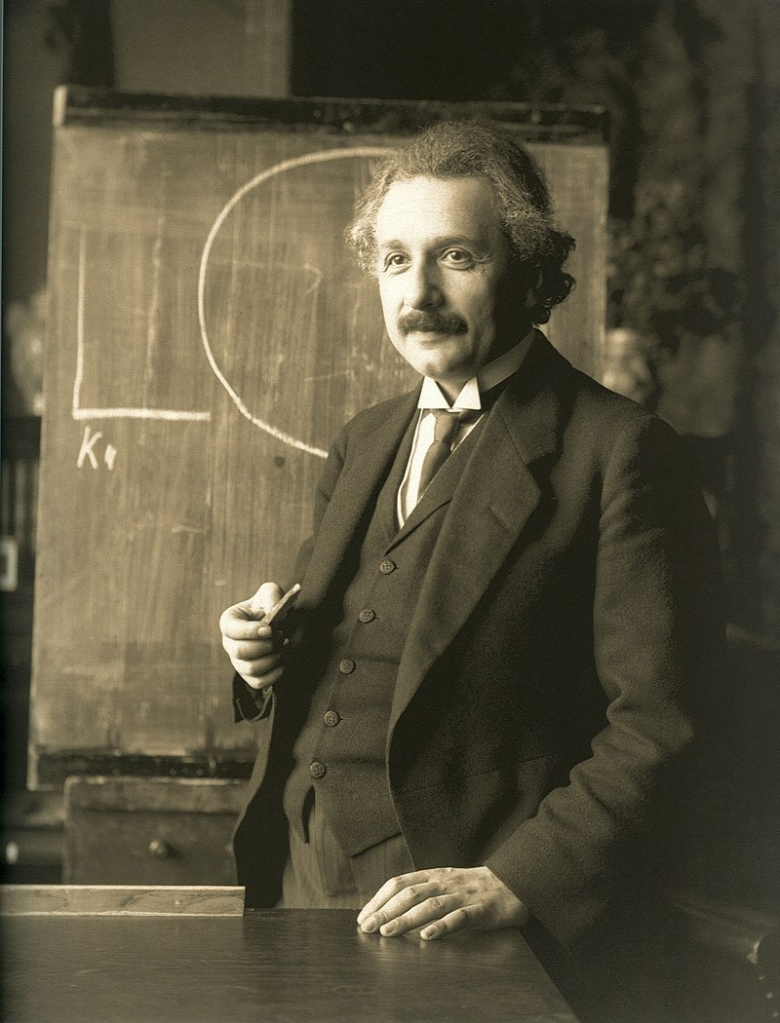

Albert Einstein observed:

“Chess holds its master in its own bonds, shackling the mind and brain so that the inner freedom of the very strongest must suffer.”

The roster of players who were finally beaten by the sport itself demonstrates just how dangerous a game chess can be.

By the end of his life, Wilhelm Steinitz, once considered the greatest chess player of the 19th century, was telling people how he had played chess with God –– and won.

Steinitz’ story follows a parabola of fame, an arc that took him to the heights of chess notoriety before dropping him into madness.

Born in Prague in 1836, Steinitz moved to Vienna as a young man to study math and, of course, play chess.

He quickly rose through the ranks to become the first undisputed World Chess Champion in 1886, a title he held for the next 8 years.

But Steinitz’ obsession went beyond playing chess.

For decades, he engaged in the “Ink War”, a battle waged from the pages of various periodicals, including the journal he founded, the International Chess Magazine, to shape the future strategy and nature of the game.

After he lost his championship title in 1894, Steinitz traveled to Russia in a bid to reclaim his top position.

But instead of winning, he suffered a mental breakdown in St. Petersburg.

Confined to a Russian sanitarium, Steinitz spent long days of confinement playing chess with any inmate up for a game.

By the turn of the century, his erratic behavior had become even more pronounced, with reports of him talking on wireless telephones and playing chess games with God.

By 1897, Steinitz’ decline was so well known that the New York Times used it to illustrate the perils of chess:

“It is not without significance that the death of Steinitz should have been due to mental disorder.

His death seems to be another admonition that ‘serious chess’ is a very serious thing indeed.”

Praised by Bobby Fischer as “perhaps the most accurate player who ever lived”, Paul Morphy unfortunately ended up better known for his unhinged behavior than his unparalleled talent.

In 1884, the New York Times’ obituary read:

“The Great Chess Player Insane For Nearly A Score of Years”

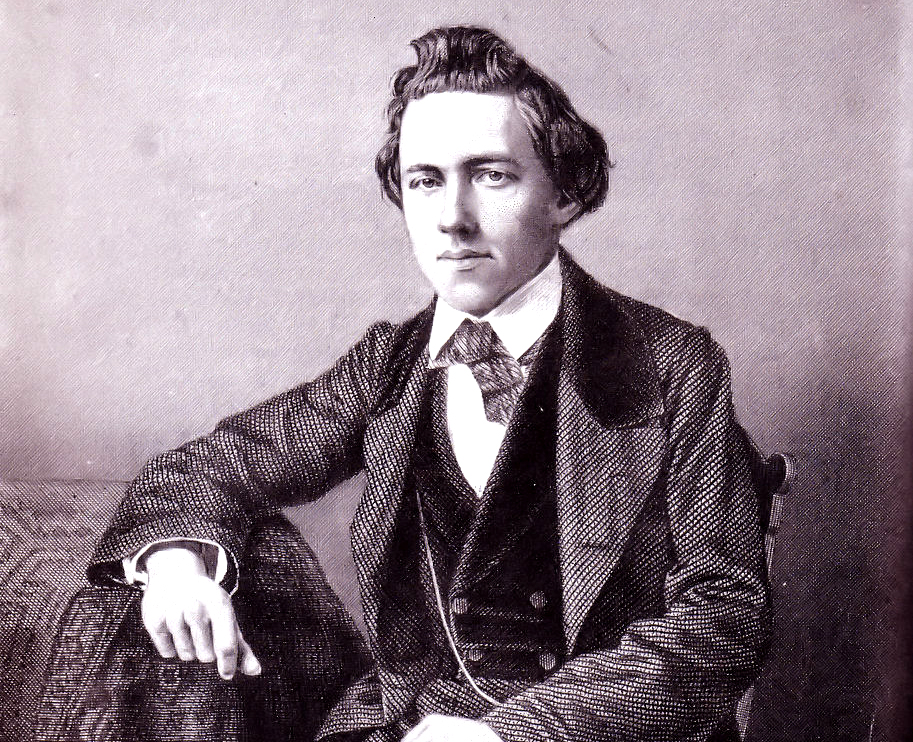

Born to a wealthy New Orleans family, Morphy learned the game by watching his uncle and father play.

By age nine, he was a local legend.

At 20, Morphy traveled to New York City, ending up becoming the United States’ first chess champion.

Having conquered America, Morphy sailed to Europe where he quickly become a cultural sensation, winning chess games and being feted in royal courts and fashionable social circles.

In 1859, Morphy returned home an American hero.

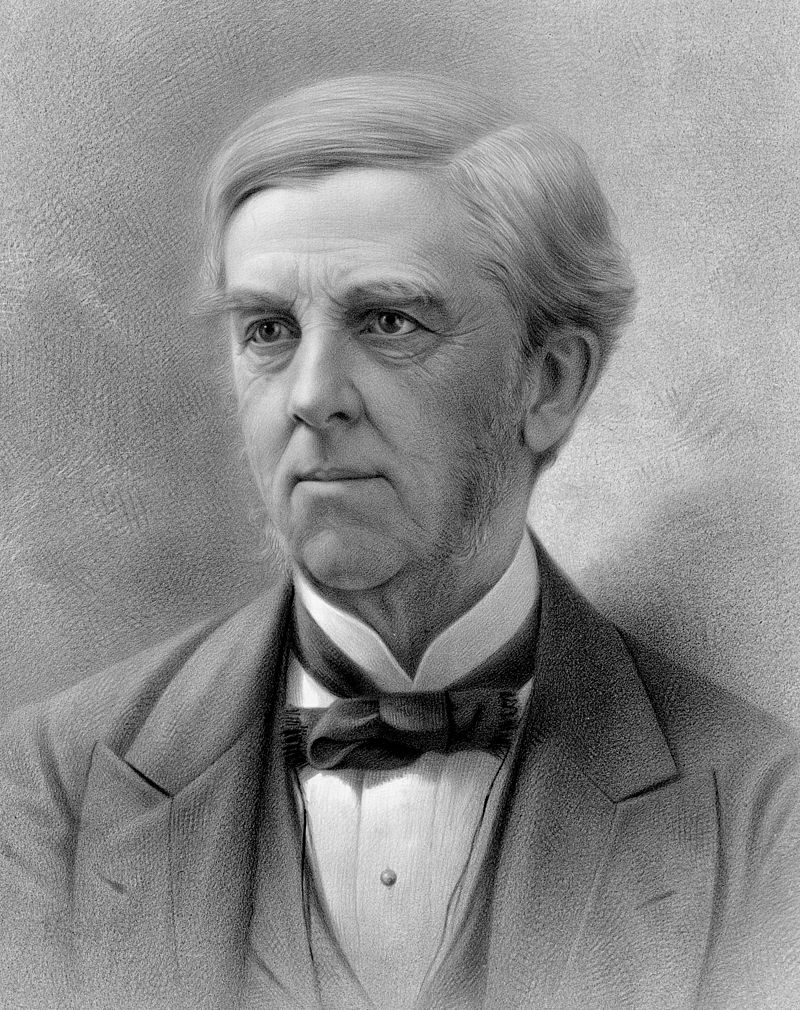

Toasting him at a special dinner in Boston, Dr. Oliver Wendell Holmes proclaimed:

“His youthful triumphs have added a new clause to the declaration of American independence.”

But soon history turned against Morphy.

The Civil War, which began shortly after his return to New Orleans, curtailed his chess playing and social life.

He tried to carve out a career as a lawyer, but his obsessive talk about chess drove potential clients away.

After the war, Morphy became a local curiosity, wandering the streets of New Orleans, loudly talking to himself or exploding in some persecution rant.

His behavior grew so erratic that friends attempted to commit him to the Louisiana Retreat, a local mental asylum.

Fighting any attempt at institutionalization, Morphy threatened to sue his friends, family and the Catholic Church.

Rumours of his odd behavior persisted until his death at 47, when, according to one legend, he died in his bathtub surround by a circle of women’s shoes.

The Polish grandmaster Savielly Tartakower once said that Aron Nimzowitsch “pretends to be crazy in order to drive us all crazy“.

For the Russian chess champion Nimzowitsch, the line between being and acting crazy was always a bit fuzzy, and, more often than not, worked to his advantage.

During the Russian Revolution, he skipped out on his military duty to the Imperial government by complaining about an invisible fly on his head.

His chess career was also assisted by his occasional bouts of madness.

He famously jumped up on the chessboard after losing a rapid-fire chess game, screaming out:

“Why must I lose to this idiot?”

At other times, he would get up from a game in order to start doing aerobics or stand on his head, acts which he swore helped him focus his mind.

Less amusing was his unshakable fear about food.

In restaurants and public dinners, Nimzowitsch would loudly complain to everyone within earshot how he was receiving less food than other people.

When waiters scrambled to substitute someone else’s meal, or add more to his plate, he would continue his complaints as if nothing had changed.

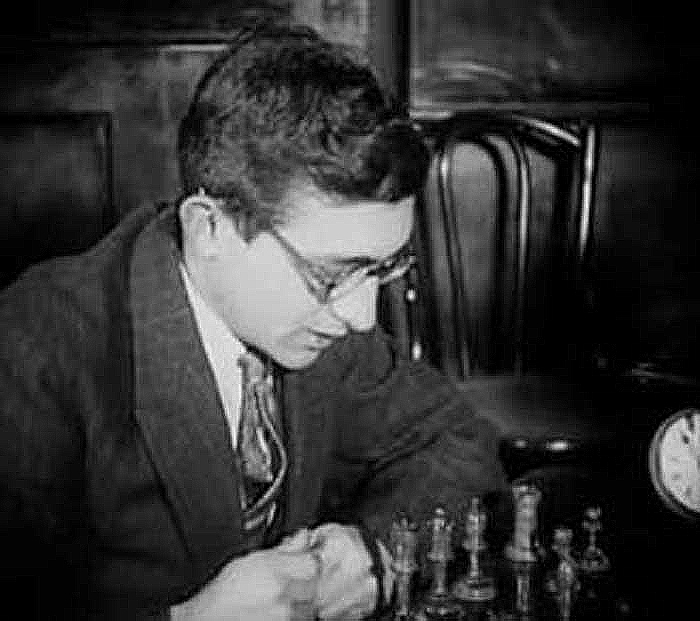

Within a few years, Carlos Torre moved from being the hero of the Mexican chess world to an exile in his own country.

At age 20, Torre started to compete seriously, and within two years he had advanced to a position where he was matched up against (and beat) the reigning world champion Emanuel Lasker.

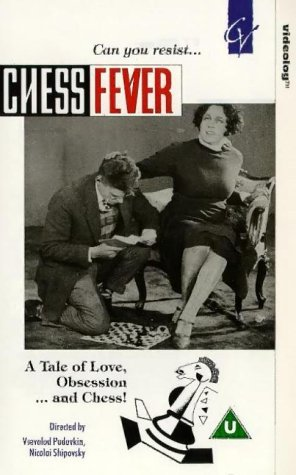

He had become so well known that made a cameo among other greats in Lev Kuleshov’s 1925 film Chess Fever.

But just as Torre was set up to become a major contender, he fell apart.

In 1926 while in New York City, Torre suffered a mental breakdown that ended with him stripping naked on a Fifth Avenue bus.

After being briefly institutionalized, he returned to his native Mexico, never to play competitively again.

For decades he lived far from the limelight, broke and nearly completely forgotten.

While some chess historians have attributed his breakdown to a recent break up with his fiancé, Torre’s friend and physician, Dr. Carlos Fruvas Gárnica, blamed his demise on the pressures of being a world-class player.

“In 1926 there was no Mexican politician, general, or rich retailer, or monopolistic millionaire that did not want that Torre went to its social gatherings,” Gárnica wrote, suspecting that “Torre retired voluntarily from chess not to have to report to that society of crazy people“.

Although the British Grandmaster Gawain Jones considers the Ukrainian player Vassily Mykhaylovych Ivanchuk “possibly the most talented ever“, others have dubbed him the world’s most peculiar player.

In 1987, at the age of 18, Ivanchuk won the European Junior Chess Championship.

The next year, he became a Grandmaster and was ranked one of the top 10 players in the world.

At 21, he beat the World Chess Champion Garry Kasparov in a single game.

Yet despite his obvious genius, there was rarely a tournament in which news of Ivanchuk’s latest antics ––from going out late at night to howl at the wind, or staring at the ceiling during a game, or trying fold an oversized winner’s check to fit in his pocket –– wasn’t the fodder of chess gossip.

World Champion Visvanathan Anand excuses the behavior of his friend by reminding everyone that “Chucky” lives on “Planet Ivanchuk“.

The British magazine Chess singled out Raymond Weinstein in their coverage of the US Championship in 1964 with the following blurb:

“Outside of Fischer, Weinstein was the one person in the tournament with real talent.

There is nothing to stop him going right to the top if he wants to, for Weinstein has a ruthless killer instinct.”

As it turned out, the compliment was an unfortunate turn of phrase, since later that year Weinstein was arrested for murder.

The Brooklyn-born chess prodigy had not only been a contemporary of Bobby Fischer but grew up in the same neighborhood, being just two years ahead of him at Erasmus High School.

In competition, Weinstein was unfortunately always a step, or two, behind Fischer.

In 1961, he placed third at the US Championship, with Fischer coming in first.

Before Weinstein could hope to catch up with Fischer, his mind snapped.

At age 22, Weinstein experienced a mental breakdown while in Amsterdam which resulted in him physically assaulting a local chess writer.

Deported back to America, Weinstein ended up in a halfway house where he slit the throat of his 83-year-old roommate.

Deemed incompetent to stand trial, Weinstein was committed to the Kirby Forensic Psychiatric Center near Manhattan, where he lives today.

When Alexander Pichushkin was arrested in Moscow in 2006 for 49 murders and three attempted murders, he asked the court to add 11 more counts to the charges against him.

His mysterious reason for wanting to raise the tally to 63 became clear when the police found a chessboard at his home with all but one of the squares filled in with the dates of his crimes.

Soon after, the press and public dubbed him “The Chessboard Killer,” and his fondness for chess provided a helpful clue into his particular madness.

While he had murdered his first victim when he was 18, Pichushkin started his killing spree in 2001, five years before he was arrested.

As a supermarket clerk who spent his free time playing chess under the leafy trees of Moscow’s Bitsevsky Park, Pichushkin often invited older homeless men to play chess with him before violently beating them to death with a hammer.

Some forensic psychiatrists imagined a link between these old men and his grandfather, the man who first taught him to play chess and whose death may have been the trauma that push him over the edge.

For others the game of chess itself sheds light on Pichushkin’s sociopathic behavior.

Pichushkin was “detached from human beings,” explained psychoanalyst Tatyana Drusinova.

“Human beings were no more than wooden dolls, like chess pieces, to him.“

A cursory view of the literature wherein chess plays a crucial role in the plot reveals a morass of madness:

Kochanowski’s Chess finds two men fighting over the right to marry a princess, as if their futures hang upon winning her, but the best she can muster as intelligent input is an enigmatic opinion that knights know how to fight, priests are good at giving advice, infantry doesn’t hesitate to walk forward and that it is no loss to change a dear thing for someone beloved.

Beyond her beauty and her dowry I cannot see what benefits she offers the fortunate fellow who wins her as a prize.

Love / lust is its own kind of insanity.

Through the Looking-Glass, and What Alice Found There (also known as Alice Through the Looking-Glass or simply Through the Looking-Glass), the sequel to Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1865) is a novel published on 27 December 1871 by Lewis Carroll.

Alice again enters a fantastical world, this time by climbing through a mirror into the world that she can see beyond it.

There she finds that, just like a reflection, everything is reversed, including logic (for example, running helps one remain stationary, walking away from something brings one towards it, chessmen are alive, nursery rhyme characters exist, and so on).

“The horror of that moment,” the King went on, “I shall never never forget!“

“You will, though,” the Queen said, “if you don’t make a memorandum of it.“

It seems very pretty,’ she said when she had finished it, ‘but it’s rather hard to understand!‘

(You see she didn’t like to confess, even to herself, that she couldn’t make it out at all.)

“Somehow it seems to fill my head with ideas — only I don’t exactly know what they are!“

“Why, sometimes I’ve believed as many as six impossible things before breakfast.“

“…and he was going on, when his eye happened to fall upon Alice:

He turned round rather instantly, and stood for some time looking at her with an air of the deepest disgust.

“What—is—this?” he said at last.

“This is a child!” Haigha replied eagerly, coming in front of Alice to introduce her, and spreading out both his hands towards her in an Anglo-Saxon attitude.

“We only found it to-day. It’s as large as life, and twice as natural!“

“I always thought they were fabulous monsters!” said the Unicorn.

“Is it alive?“

“It can talk,” said Haigha, solemnly.

The Unicorn looked dreamily at Alice, and said:

“Talk, child.”

Alice could not help her lips curling up into a smile as she began:

“Do you know, I always thought Unicorns were fabulous monsters, too!

I never saw one alive before!“

“Well, now that we have seen each other,” said the Unicorn, “if you’ll believe in me, I’ll believe in you.

Is that a bargain?“”

“It is a very inconvenient habit of kittens (Alice had once made the remark) that, whatever you say to them, they always purr.

“If they would only purr for “yes” and mew for “no,” or any rule of that sort” she had said, “so that one could keep up a conversation!

But how can you talk with a person if they always say the same thing?“”

Children yet, the tale to hear,

Eager eye and willing ear,

Lovingly shall nestle near.

In a Wonderland they lie,

Dreaming as the days go by,

Dreaming as the summers die:

Ever drifting down the stream —

Lingering in the golden gleam —

Life, what is it but a dream?

Madness.

Nabokov’s The Defence‘s main character, Aleksandr Luzhin, suffers from mental problems because of his obsession with chess.

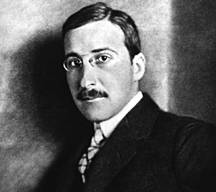

Stefan Zweig’s The Royal Game is set on a passenger liner travelling from New York to Buenos Aires.

One of the passengers is a world chess champion, Mirko Czentovic, an idiot savant and prodigy with no obvious qualities apart from his talent for chess.

Another is a lawyer who managed the assets of the Austrian nobility and church, who was arrested by the Gestapo who hoped to extract information from Dr B. in order to steal the assets.

The Gestapo kept Dr B. imprisoned in a hotel, in total isolation, but Dr B. maintained his sanity by stealing a book of past masters’ chess games, which he learned completely.

After absorbing every single move in the book, he began to play against himself, developing the ability to separate his psyche into two personas.

This psychological conflict ultimately caused him to suffer a breakdown, after which he awakened in a hospital.

A sympathetic physician attested his insanity to keep him from being imprisoned again by the Nazis, and he was freed.

In a stunning demonstration of his imaginative and combinational powers, Dr B. beats the world champion.

The champion suggests another game to restore his honour.

Dr B. immediately agrees, but this time, having sensed that Dr B. played quite fast and hardly took time to think, Czentovic tries to irritate his opponent by taking several minutes to make each move, thereby putting psychological pressure on Dr B., who gets more and more impatient as the game proceeds.

His greatest power turns out to be his greatest weakness:

He devolves into rehearsing imagined matches against himself repeatedly and manically.

Czentovic’s slow deliberation drives Dr B. to distraction and ultimately to insanity.

So much of who chess masters are – hinging on the outcome of a game.

John Brunner’s sci-fi novel The Squares of the City is a sociological story of urban class warfare and political intrigue, taking place in the fictional South American capital city of Vados.

It explores the idea of subliminal messages as political tools,

It is notable for having the structure of a famous 1892 chess game between Wilhelm Steinitz and Mikhail Chigorin.

The structure is not coincidental and plays an important part in the story.

In Darren Shan’s Lord Loss, Grubitsch “Grubbs” Grady, the younger child of chess-obsessed parents, grows increasingly uneasy with the recent strange, nervous behavior of his parents and sister.

One night, he finds the mutilated bodies of his family and encounters Lord Loss, a gruesome human-like demon who sets his two familiars, Vein and Artery, on Grubbs.

Although Grubbs manages to escape, he is deeply traumatized and is placed in a mental institute.

He refuses to respond to treatment until he is visited by his father’s younger brother, Dervish Grady, who tells Grubbs that he knows demons exist and convinces Grubbs to finally accept help.

The only way to cure him is by winning three out of five simultaneous chess games with the powerfully magical demon master Lord Loss.

While confronting Lord Loss, Dervish is constantly distracted from his chess match.

Dervish is able to convince Lord Loss to let Grubbs finish the chess game.

Grubbs realizes that Lord Loss is feeding on his despair and then decides to play with an aloof attitude.

This throws Lord Loss’ concentration, allowing Grubbs to win the game.

Jonathan Lethem’s Dissident Gardens finds Uncle Lenny, who once played Bobby Fischer to a draw as a participant in a simultaneous exhibition in which Fischer defeated everyone else, destroying the chess confidence and ambitions of a young Cicero.

Cicero does so badly that he swears off chess forever.

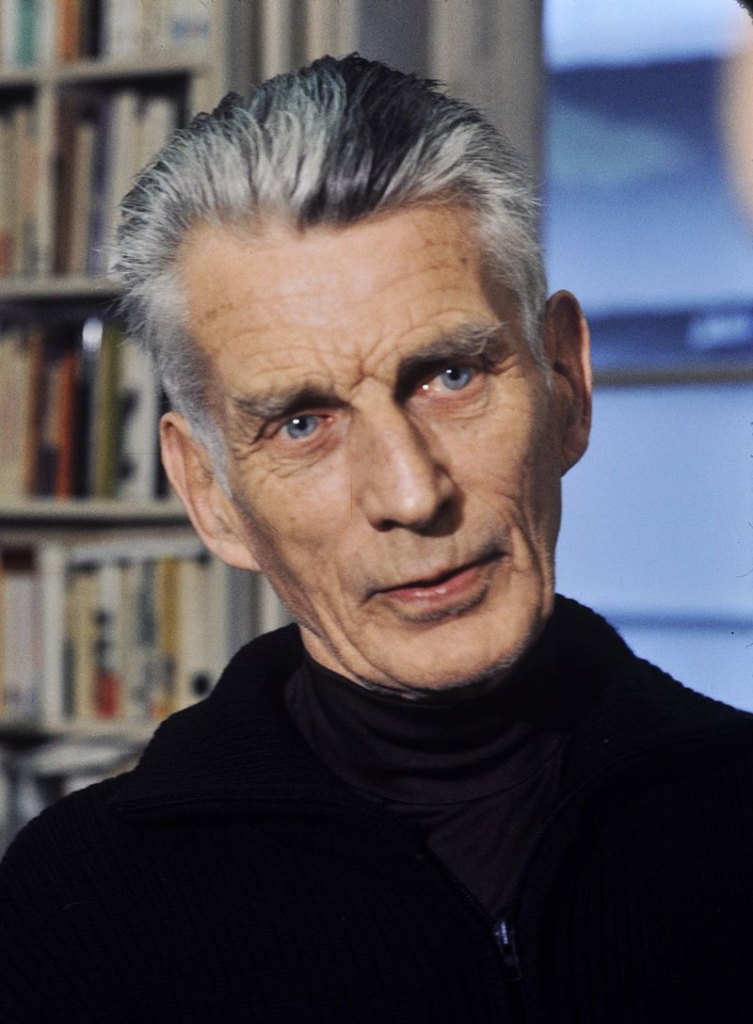

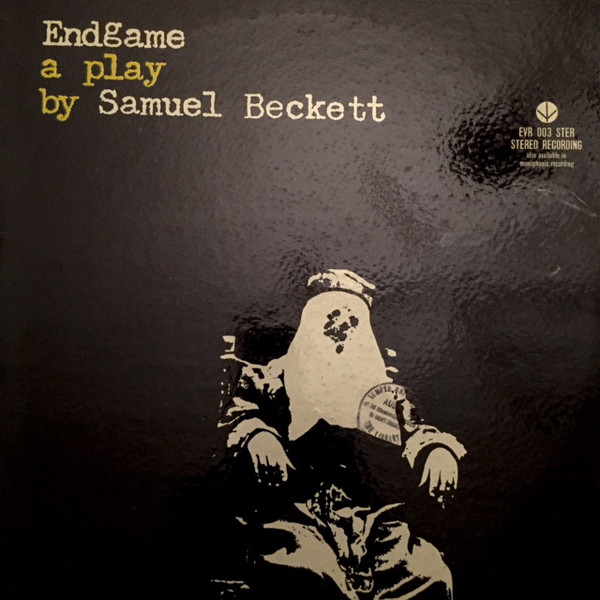

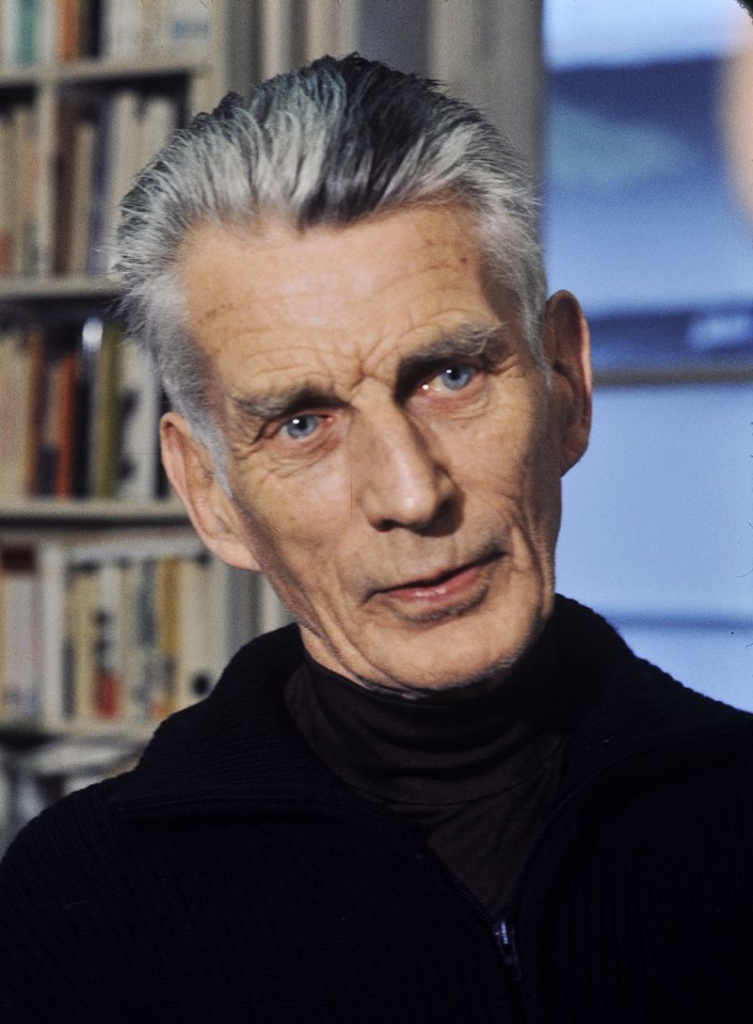

Endgame, by Samuel Beckett, is an absurdist, tragicomic one act play about a blind, paralyzed, domineering elderly man, his geriatric parents and his doddering, dithering, harried, servile companion in an abandoned shack in a post-apocalyptic wasteland who mention their awaiting some unspecified “end” which seems to be the end of their relationship, death, and the end of the actual play itself.

Much of the play’s content consists of terse, back and forth dialogue between the characters reminiscent of bantering, along with trivial stage actions.

The plot is held together by the development of a grotesque story-within-a-story the character Hamm is writing.

The play’s title refers to chess and frames the characters as acting out a losing battle with each other or their fate.

Endgame is an expression of existential angst and despair and depicts Beckett’s philosophical worldview, namely the extreme futility of human life and the inescapable dissatisfaction and decay intrinsic to it.

The existential feelings buried in the work achieve their most vocal moments in lines such as:

“It will be the end and there I’ll be, wondering what can have brought it on and wondering why it was so long coming.”

“Infinite emptiness will be all around you, all the resurrected dead of all the ages wouldn’t fill it, and there you’ll be like a little bit of grit in the middle of the steppe.“

In both Hamm seems to contemplate the sense of dread awakened by the obliterating force of death.

Endgame is also a quintessential work of what Beckett called “tragicomedy”, or the idea that, as Nell herself in the play puts it:

“Nothing is funnier than unhappiness.”

Another way to think about this is that things which are absurd can be encountered both as funny in some contexts and horrifyingly incomprehensible in others.

Beckett’s work combines these two responses in his vast artistic vision of depicting not a segment of lived experience but the very philosophical nature of life itself, in the grandest view, as the central subject material of the play.

To Beckett – due to his existential worldview – life itself is absurd, and this incurs reactions of both black mirth and profound despair.

To Beckett, these emotions are deeply related, and this is evident in the many witty yet dark rejoinders in the play, such as Hamm’s comment in his story, “You’re on Earth, there’s no cure for that!”, which both implies in a melodramatic fashion that being born is a curse, but sounds perhaps like a biting, bar-talk joke, such as telling someone “You’re Irish, there’s no cure for that!”

Much of Beckett’s core thought which is expanded on in Endgame is in his critical analysis of Marcel Proust, entitled “Proust”.

In it, he explains his Schopenhauerian view of the human will endlessly chasing after momentary satisfaction that it can rarely if ever constantly attain, which lies behind the image of “grain upon grain” (moments in life and time) never amounting to “the impossible heap” (some fixed, non-transient accumulation or deposition of enduring value, in time).

Themes in Endgame include:

- decay

- insatiability and dissatisfaction

- pain

- monotony

- absurdity

- humour

- horror

- meaninglessness

- nothingness

- existentialism

- nonsense

- solipsism

- people’s inability to relate to or find completion in one another

- narrative or story-telling

- family relations

- nature

- destruction

- abandonment

- sorrow

Endgame is lurching, starting and stopping, rambling, unbearably impatient, and sometimes incoherent.

Much the way I attempt to play chess.

In fact, it almost seems like a parody of writing itself.