Eskişehir, Türkiye, Monday 8 August 2022

Two days I returned from travelling in Switzerland, Germany and Malta.

What defines a person’s travelling, a person’s life, is not only the things they decided to do, but as well the things they decide (or are unable) to do.

I consider Malta.

We visited, and used as a travel base, Valletta.

We visited Vittoriosa, Sliema, Paola, Marsaxlokk, Rabat and Mdina on the island of Malta itself.

We visited Victoria and Marsalforn on the island of Gozo.

The list of what we saw in all these places is worthy of many blogposts so I will not list these all here.

Suffice to say that choices, determined by both limited time and money, had to be made as to what we would see and what we wouldn’t see.

We ate well, slept well, saw and did many wonderful things.

What was rarely seen during our stay in Malta were stray animals.

We saw some in the San Anton Gardens, attached to the same-named Palace, in Attard.

The early 17th century Palace once served as the official residence of the British Governor of Malta and is now that of the Maltese President.

The lovely walled Gardens contain groves of citrus and avocado as well as an aviary.

Wandering at will through the Gardens were pigeons, doves, peacocks, ducks and cats.

Though we were in Marsaxlokk, close to St. Peter’s Pool, one of the most beautiful and stunning natural swimming spots that the Maltese littoral has to offer, it was rather remote and hard to access, which is sad, for we missed an opportunity to see the dynamic duo of Carmelo Abela and Titti.

Abela and his pet, a Jack Russell terrier called Titti, became famous after a video of their perfectly coordinated synchronized dives went viral worldwide.

The dog never hesitates to leap off 12-foot cliffs, perfectly breaking the surface of the water together with her loving and devoted provider.

Abela and Titti go down to St. Peter’s Pool almost everyday in summer, (the temperature was a constant 33°C when we were there), where locals and foreigners alike hope to see them perform and maybe get a picture of the famous airborne dog.

Titti is a loyal dog and will only jump with her provider, Abela says.

Totally enamoured with the sea, she barely gives him time to get off his motorbike before she runs off and leaps off the edge into the gin-clear waters.

Titti is adored by everybody who sees her.

She even has her own Facebook page.

I don’t envy Abela’s ability to train Titti.

I envy him the love and loyalty that Titti shows him.

Denizli, Türkiye, Friday 23 July 2022

The bus is late, ETA was 1800, it is nearly 1830.

I don’t care, for on the benches where passengers wait for their buses, a kitten stretches.

I pet and stroke it.

To my surprise and delight it jumps upon my lap, stretches up across my chest and nuzzles its head in the crook of my arm.

It is love, instant and pure.

I feel like a royal bastard, picking it off me, putting back on the bench where I found it, and boarding the bus back to Eskişehir.

Eskişehir, Türkiye, Saturday 23 July 2022

The cat had its revenge, kitten’s karma.

After dinner stopover of 30 minutes in Uşak, the journey back to Eskişehir and my apartment therein was unpleasant.

A sour puss of a passenger sits beside me and promptly falls asleep, snoring loudly.

The TV console built into the back of the seat in front of me does not function.

The roaming option on my cellphone expired mid-journey.

A manly woman (transgender?) shouts into her phone loudly.

She is heard by everyone except maybe a man in a coma in Dubai.

I miss the days when the only ways to talk on the phone were from home or at a curb telephone booth.

Instead we are all one miserable captive collective, forced to listen to the mutterings of the mad, the loud lout lunatics and the exclamations of the exasperated emotional expressive.

The final fatal feeling was the man I call the Taxi Nazi.

He is possibly the only taxi driver in Türkiye who still wears a protective face mask, who insists passengers wear their seat belts, whose shotgun seat does not slide backwards, meaning a tall man like myself sits uncomfortably cramped beside the driver, who is unfriendly and impersonal as an IRS agent at your door requesting an audit of your delinquent taxes.

I once again deny him extra fare and have him stop several blocks away from my apartment.

Morning comes.

I have an appointment to pick up dry cleaning from a shop close to my old apartment near ES Park shopping centre.

The tie could be cleaned.

The stain on my recently-purchased (in Sinop) long-sleeved blue shirt is permanent.

I think of the cupboards bare in the apartment and I wait outside ES Park mall for it to open its doors so I can descend downstairs to Migros and buy some last minute groceries for the day and the next.

A quartet of dogs playfully scamper around me and the half dozen others waiting for security to grant us access to the mall’s interior.

Each dog in its turn seeks affection and attention from me.

I am soft-hearted.

I need love.

I need to love.

I need to be loved, if only by an animal.

Again, I do the bastard deed.

I walk away.

Landschlacht, Switzerland, Wednesday 27 July 2022

Tomorrow, we (the wife and I) fly from Zürich, Switzerland to Valletta, Malta, and, of course, we have pondered what we will see when we get to this ocean paradise.

One attraction that is promoted on the islands that make up this Mediterranean nation is the L’Arka ta’ Noe (Noah’s Ark) – the largest zoo on the islands.

Siberian and Bengal tigers are an important highlight of the park.

At L-Arka ta’ Noe, one can admire from a close distance three extremely unique tigers – the Golden Tabby, the pure white tiger, and a black and white tiger.

These adorable creatures will undoubtedly leave you with a remarkable smile.

Above: L’Arka ta Noe, Triq Bur ix-Xewk, Siggiewi, Malta Island, Malta

I once again face a moral dilemma over this idea.

From Warren Agius, https://www.change.org :

Before anyone considers going to l’Arka ta Noe, please keep these factors in mind.

I have no intentions on damaging their business, quite frankly I don’t care.

I only care about the well-being of the animals which are being held in that environment.

They do not deserve this ill-treatment and someone has to speak-up for them.

If you care about animals and their welfare in any way, please continue reading this post.

Just a bit of background information, l’Arka ta Noe has a lot of exotic animals.

The problem about this place is that these animals are not seen as living beings, but are seen as objects.

In fact, their own website says the following:

“He started this magnificent park with only a few animals and at first it was only a private collection.”

That’s right, a collection.

And this is exactly how these animals are being treated, as a way to make money.

It is important to keep in mind the following:

- Tigers are meant to HUNT for their food.

These tigers are fed by a person literally throwing pieces of meat on the floor.

- The tigers cannot practice their natural instincts at all in such a confined and limited space.

There are three FULLY GROWN tigers in one enclosure.

It doesn’t matter if they are there for feeding or not.

Just one fully grown tiger travels approximately 16-32 km a day just to search for food.

- Animals in captivity suffer from psychological distress.

When I visited the place, the tigers could be seen pacing back and forth and were aggressively jumping at the fence.

They did not seem healthy or happy at all.

This place does not resemble / imitate their original wild-life habitat AT ALL.

Hopefully, places like this one, which keep these beautiful animals in captivity, are punished for completely disregarding the animals’ well-being.

A zoo (short for zoological garden; also called an animal park or menagerie) is a facility in which animals are housed within enclosures, cared for, displayed to the public, and in some cases bred for conservation purposes.

The term zoological garden refers to zoology, the study of animals.

The term is derived from the Greek ζώον, zoon, ‘animal‘, and the suffix -λογία, -logia, ‘study of‘.

The abbreviation zoo was first used by the London Zoological Gardens, which was opened for scientific study in 1828 and to the public in 1847.

In the United States alone, zoos are visited by over 181 million people annually.

The first zoos I ever visited were during my walking adventures back in my 20s – the Toronto Zoo and the Montréal Biodome.

I have since then visited:

- the Wildfowl and Wetland Trust, Slimbridge, Gloucestershire, England

- the Mundenhof Animal Park, Freiburg im Breisgau, Baden-Württemberg, Germany

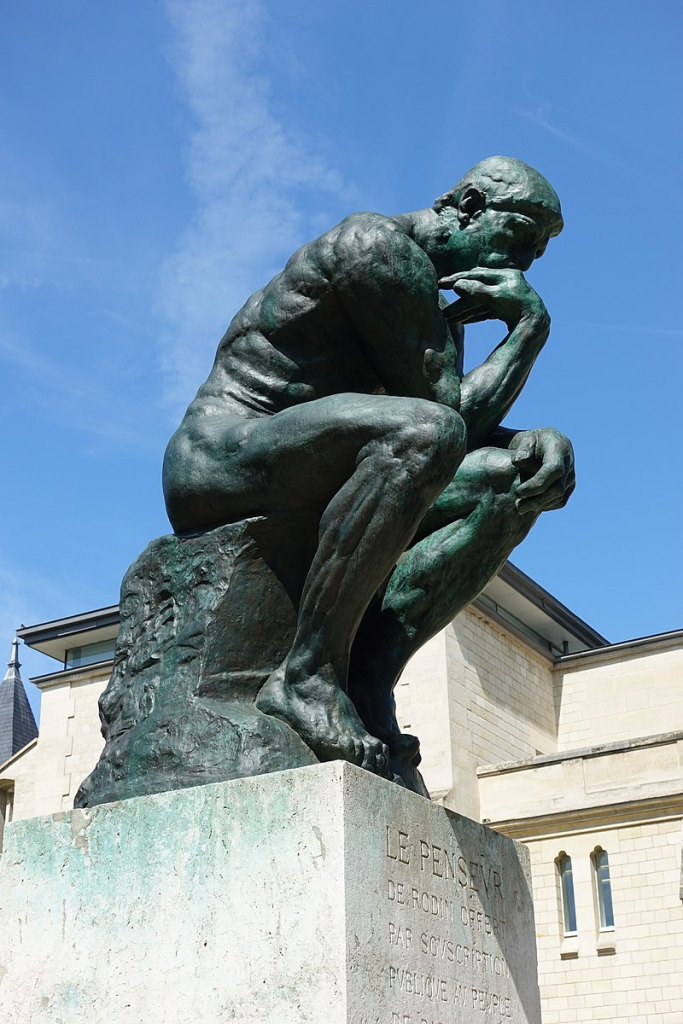

- the Osnabrück Zoo, Osnabrück, Niedersachen, Germany

- the Knies Kinderzoo, Rapperswil, Canton St. Gallen, Switzerland

- Wildpark St. Peter und Paul, St. Gallen, Switzerland

- Zoo Basel, Basel, Switzerland

- Zürich Zoologischer Garten, Switzerland

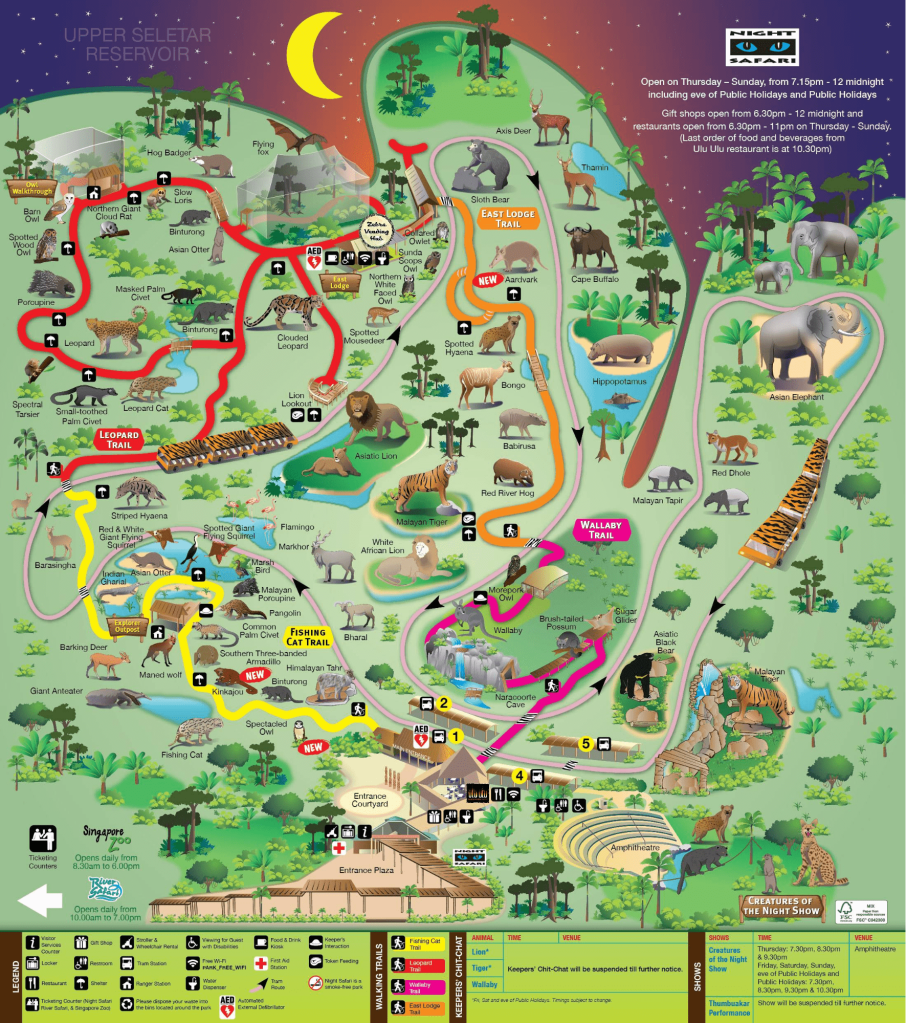

- Night Safari, Singapore

- Perth Zoo, Western Australia

- Walter Zoo, Gossau, Canton St. Gallen, Switzerland

The visit to this last aforementioned zoo, on 4 January 2022, is what has inspired this post.

Gossau, Canton St. Gallen, Switzerland, Tuesday 4 January 2022

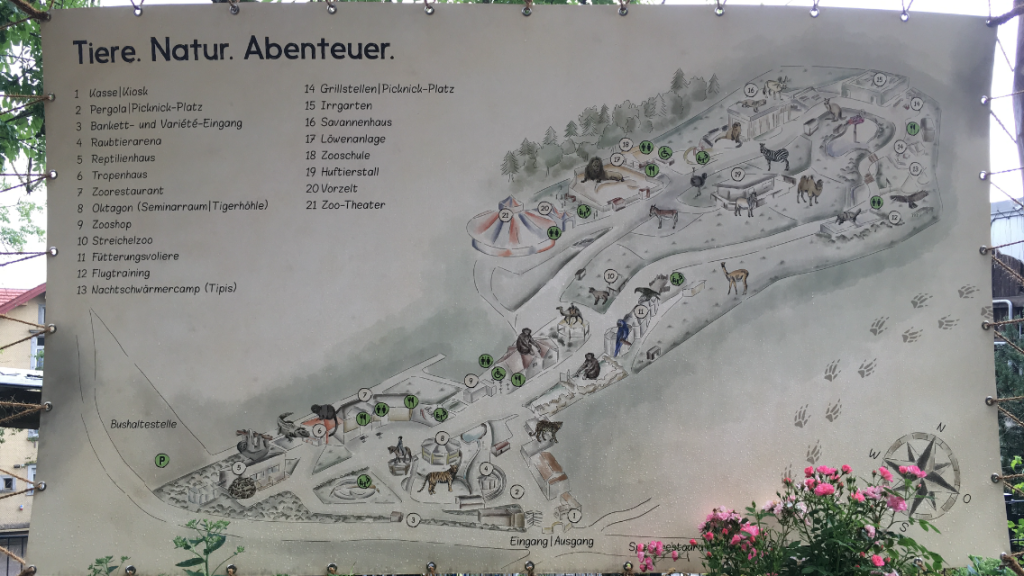

The Walter Zoo is a zoological garden above Gossau near the city of St. Gallen.

It houses around 1,110 animals in over 120 animal species (2019).

On the 5.5 hectare site there are also numerous play and relaxation options for children.

The Zoo also has 4.5 hectares of adjacent land, which can be expanded over the next few years in accordance with the 2040 master plan.

With around 250,000 visitors per year, the Walter Zoo is one of the most popular destinations in eastern Switzerland.

As a scientifically run zoo, it is a member of EAZA and Zoo Schweiz, among others.

In addition, it is involved in 21 (as of 2021) conservation breeding programs for endangered animal species and supports nature conservation projects in various countries financially.

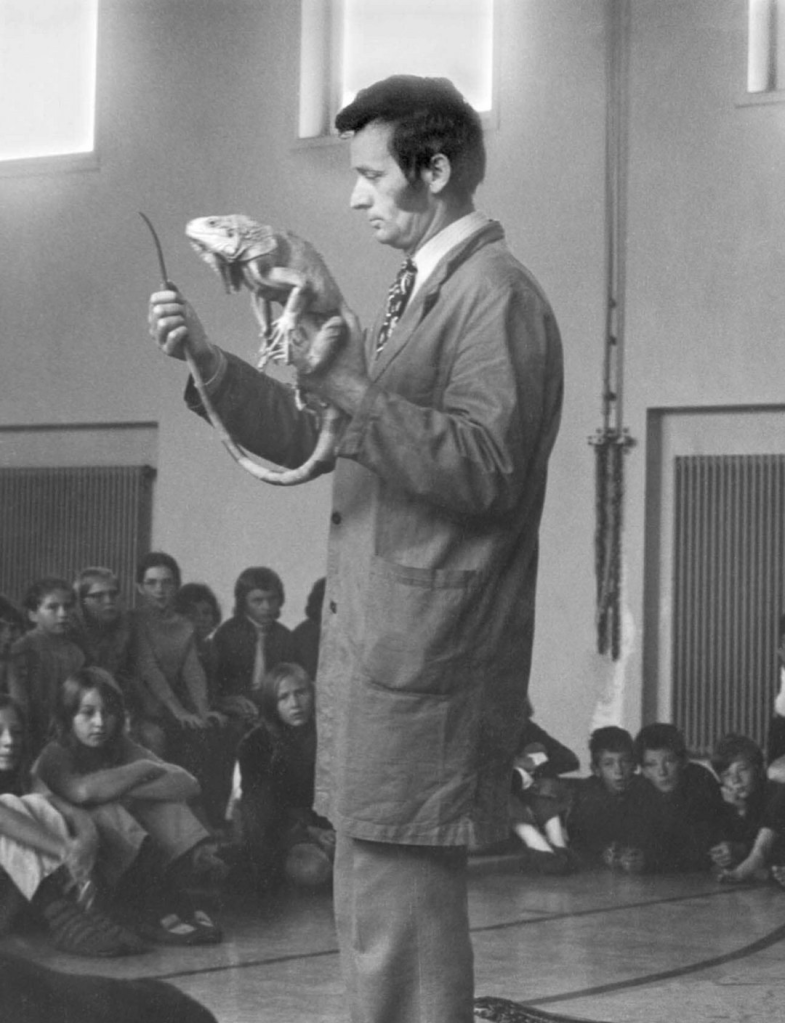

The Walter Zoo was founded in 1961 by Walter and Edith Pischl in Gossau.

After a few years as circus artists in the Nock Circus, Walter (from an Austrian artist dynasty) and Edith Pischl (born in Herisau) settled down with their animals in Hundwil.

Walter visited schools with the animals and gave lectures to make them better known to people.

Due to their growing reputation, more and more sick or unwanted animals were placed in the care of the Pischl family, which made space at their old place of residence in Hundwil tight and so the family moved to Gossau.

Due to the ever-increasing maintenance costs for facilities and feed, the family decided to charge admission.

However, this hardly improved the financially difficult situation.

Therefore, the Walter Zoo Association was founded in 1963 with the help of animal lovers.

The first house was built for the chimpanzees in 1973, it is now the oldest house in the zoo and is now used as a “Reptile House“.

The current reptile house was built as the first house in 1973.

Various reptiles and amphibians, such as Burmese pythons, guince monitors, stump crocodiles, Egyptian tortoises or moor frogs can be admired.

The upper, semi-open floor is inhabited by South American animal species, such as agoutis, white-headed sakis, two-toed sloths, globe armadillos and yellow-breasted macaws.

In the adjacent tropical house, where the restaurant is located is home to animals such as:

- alligators

- Emperor tamarins

- jumping tamarins

- night monkeys

- peacock rays

- crocodile tejus

- green anacondas

Thanks to the Walter Zoo Verein, additional land could be purchased in 1980.

In 1983, the hoofed animal stable and new bird aviaries were set up along the path.

In 1985, Walter and Edith Pischl handed over the zoo to Gabi (the youngest daughter) and Ernst Federer.

Just one year later, the ground-breaking ceremony for the tropical house with the zoo restaurant followed.

The Walter Zoo opened the largest chimpanzee facility in Switzerland in 1993.

The facility is inhabited by 15 chimpanzees (as of 2021), making it the largest chimpanzee group in Switzerland.

In 1995, Walter Pischl died unexpectedly.

He had a strong influence on the zoo until his last days.

He was also significantly involved in the construction of the new, large chimpanzee enclosure, which began in 1993.

In 1997, the Walter Zoo became a member of the European Association of Zoos and Aquaria (EAZA).

This resulted in close cooperation with other zoos in Europe.

In 2001, the private zoo was converted into a public limited company (plc).

Since 2006, the Walter Zoo has been a non-profit corporation.

In 2009, the new tiger facility and the new octagonal office building with seminar and meeting rooms were opened.

In addition, the restaurant Panorama, which is located just a few meters from the zoo, was taken over.

In 2011, the third generation joined the management with the two granddaughters of Walter Pischl, Karin Federer (veterinarian) and Jeannine Gleichmann-Federer (artist).

Between October 2012 and January 2013, the Body Worlds of Animals exhibition was held at the Zoo.

In 2013, the flamingo facility was renewed.

In 2014, a new veterinary station was opened.

In 2015, the outdoor facility for the chimpanzees was renovated.

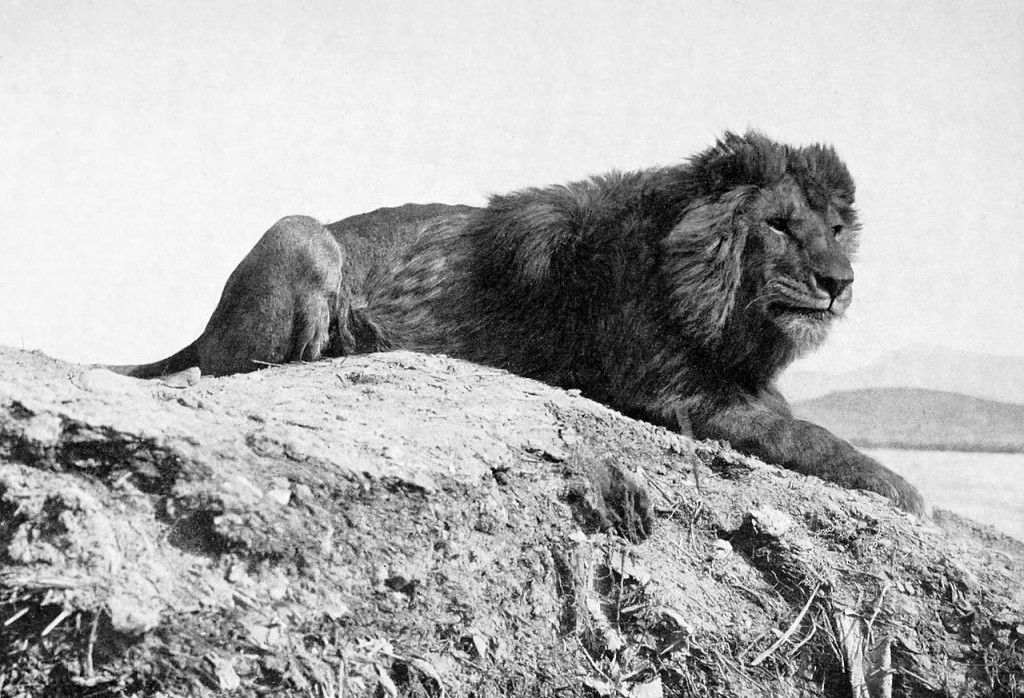

The Savannah House opened in 2017 and the new lion enclosure in autumn 2018.

After more than ten years, when the lions were given away for the expansion of the tiger enclosures, lions came back to the Zoo.

It is the near extinct subspecies of the Barbary lion.

The Savannah House was opened with the focus on the savannah habitat.

A large part is the meerkat enclosure, which the meerkats share with the spurred tortoises.

But less well-known animals such as gundi, African egg snakes, naked mole rats or fennec can be admired.

However, the crowd favorite is the chameleon.

With the opening of the new lion enclosure in autumn 2018, the lions came back.

Three animals of the Barbary lions, now extinct in nature, inhabit the complex.

The generously designed outdoor area is the heart of the new themed area, which visitors can see from several sides.

The new zoo school was opened with the new lion enclosure.

The zoo school is located above the indoor area, which is connected to the outdoor area by a terrace.

Various animals are also integrated into the zoo school, from bacon beetles to giant centipedes and cockroaches to bearded dragons.

Together with the lions, the tiger enclosure forms the heart of the predator enclosures at the Walter Zoo.

The Siberian tiger is the largest subspecies of tigers.

Young animals were born in 2018.

The keeping of Amur leopards was abandoned in 2021.

In the Petting Zoo, Bactrian camels, zebras and vicuñas, Shetland ponies and other hoofed animals can be admired and fed hay pellets.

With the African pygmy goats you can enter their enclosure to pet and feed them.

The pond landscape in the northern part of the zoo offers space for various species of ducks, such as moor ducks, marmots, red-crested pochards and pintails.

The flamingos are also popular, with offspring having been successfully bred for the first time in 2018.

There were youngsters again in 2019.

The walk-in aviary with galahs, budgies and horned parakeets is also popular.

Along with St. Gallen pigeons, yellow-breasted macaws, barn owls and desert buzzards are also trained.

This flight training can be admired on Wednesdays and Fridays in summer.

With the petting zoo, camel and pony rides, and the walk-in bird aviary, the Zoo’s offerings are strongly focused on families.

From the end of March to mid-October, the Zoo Theater takes place with a program that changes every year.

During the approximately one-hour performance, nature conservation issues are conveyed to children in an understandable way.

During the winter months, the traditional Tingel-Tangel variety show offers entertainment for adults with a four-course meal.

In summer it is also possible to stay in a tipi tent at the zoo and be guided through the Zoo at night and early in the morning.

The new logo, which the Zoo has had since spring 2020 and on which the chimpanzee has been replaced by a dragonfly in a meadow, is intended to illustrate the Zoo’s commitment to nature and species conservation.

Like every scientifically managed zoo, the Walter Zoo also has a master plan that specifies the development of the Zoo up to the year 2040.

In 2017, the Zoo was able to acquire land in the southwestern part, which gives the Zoo the opportunity to build new facilities.

The biggest change is likely to be the planned relocation of the entrance from the upper part of the zoo to the parking lot.

In spring 2022, the first facility of the master plan with pygmy otters and red pandas opened.

The Walter Zoo has a wide educational range, which was expanded with the opening of the zoo school in autumn 2018.

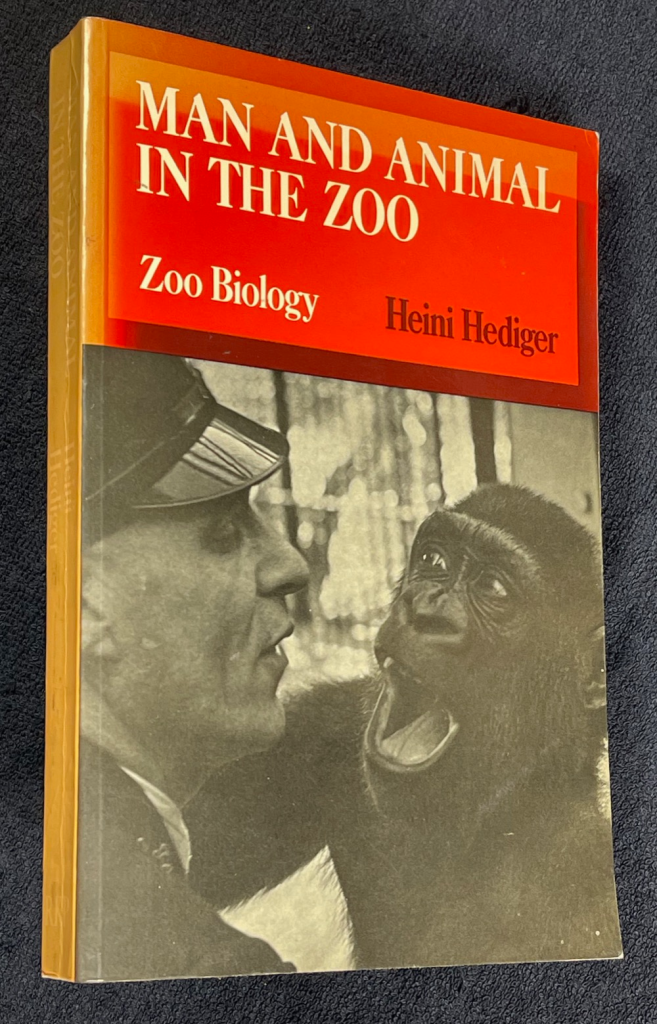

The zoo school was built in the style of an African lodge and shows the four major pillars of a scientifically managed zoo according to Heini Hediger:

- nature and species protection

- education

- research

- recreation

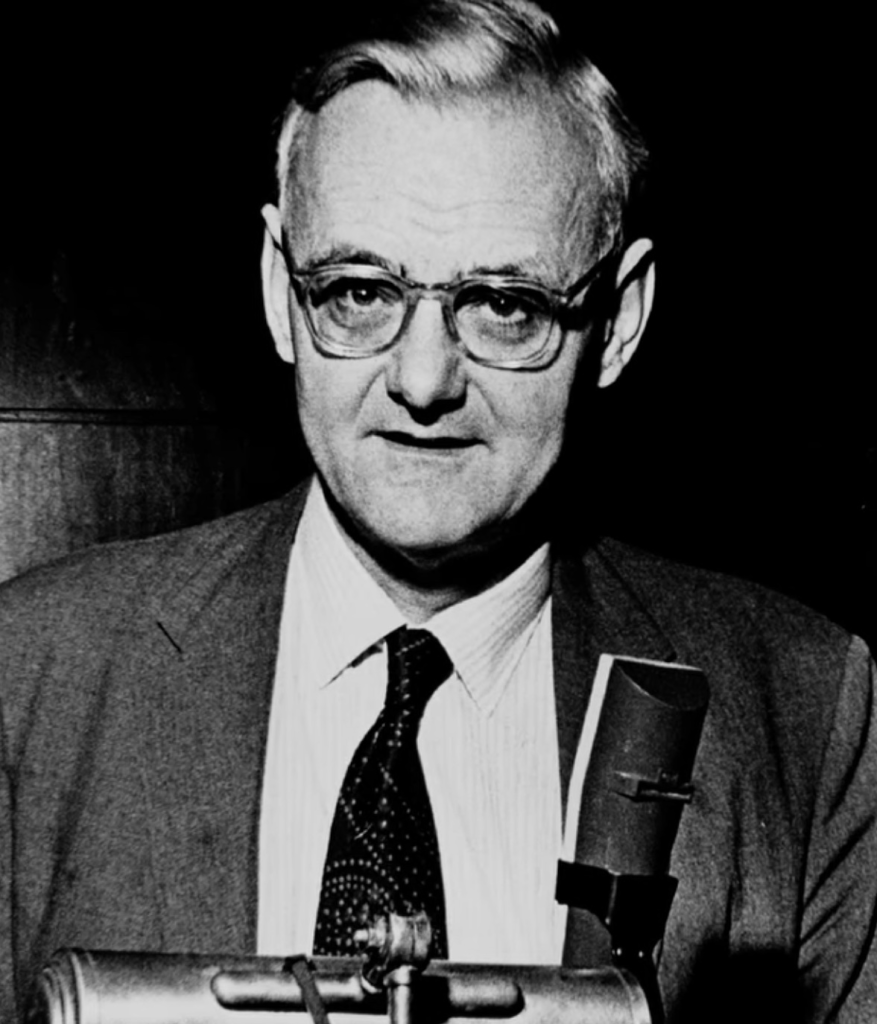

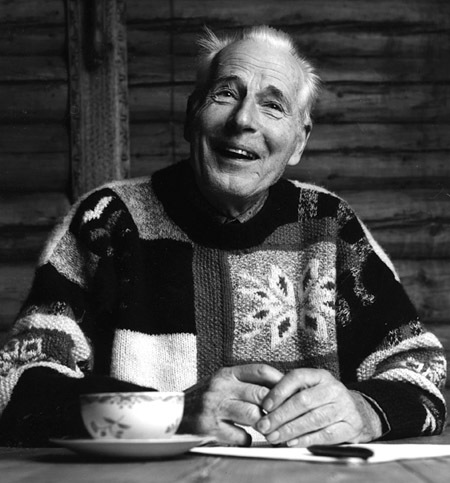

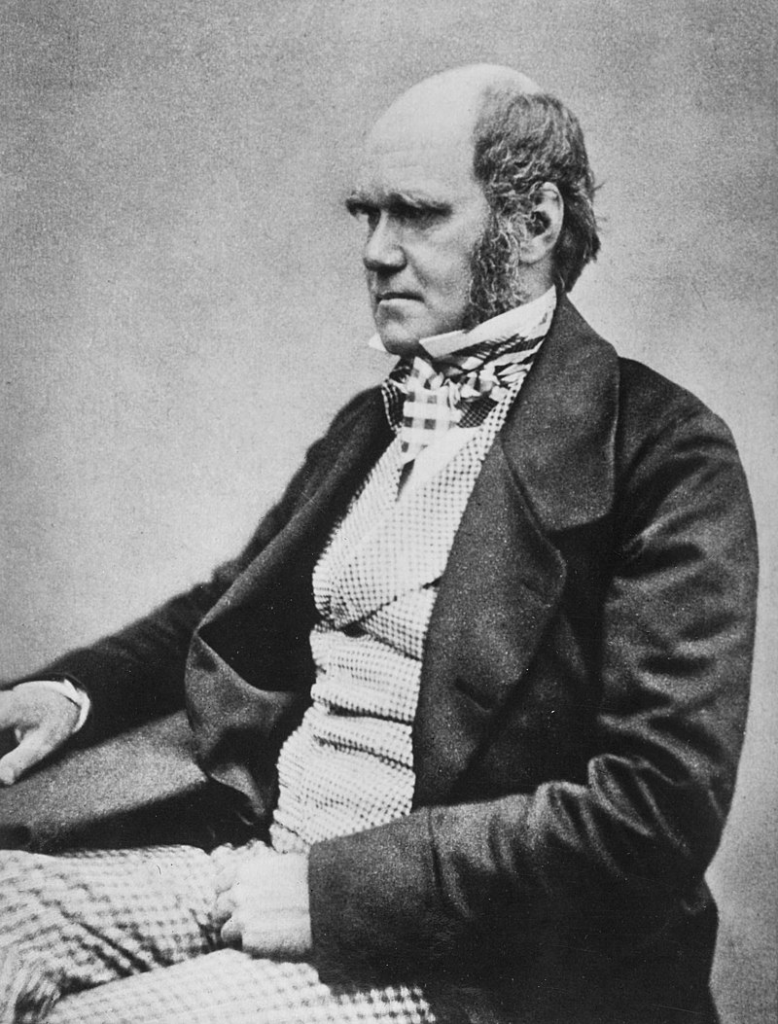

Heini Hediger (1908 – 1992) was a Swiss biologist noted for work in proxemics (the study of human use of space and the effects that population density has on behaviour, communication, and social interaction) in animal behavior and is known as the “father of zoo biology“.

Hediger was formerly the director of Tierpark Dählhölzli, Zoo Basel and Zürich Zoo.

In his book Wild Animals in Captivity, a Sketch of Zoo Biology, Hediger drew largely on his experiences as director of the Dählhölzli Zoo.

Through the scientific studies he initiated, he found out, for example, that female rabbits can become pregnant again even before they have given birth to their young.

However, his activities were not limited to administrative matters, as he often had to replace animal keepers who were conscripted into military service.

He himself described his time in Bern as “hard school“.

Difficulties in obtaining animals and feed were the order of the day.

Despite the difficult circumstances, the Zoo received support from the zoo association.

In 1949, the Basel Zoo’s first okapi, named Bambe, died after only two months of a severe worm infection.

With this animal, Hediger was able to gain important experience in keeping the okapi, which later made successful keeping in European zoos possible.

In addition, very rare spectacled bears found their way into the bear enclosure.

Two years later, Hediger took care of the expansion of the Zoo and finally in 1951 a second entrance could be opened.

The sea lion pool was surrounded by a spectator ramp.

The giraffes were given a spacious run.

The first Indian rhino male was imported to Basel Zoo in the same year.

A year later, a female animal followed.

The bull Gadadhar and the female Joymothi form the future progenitors for the famous Basel rhino breed.

In 1952, five young elephants from East Africa arrived at the Zoo.

The group quickly became known because they were taken on regular walks through the city.

A year later, the new elephant house opened, which, in addition to the new African arrivals, is also home to the Indian rhinoceros and the pygmy hippopotamus.

A major success for Basel Zoo was the arrival of an adult pair of gorillas, as Basel was the first zoo in Europe to have one.

The era of the scientifically managed Zürich Zoo began with Heini Hediger .

At the beginning of his tenure, in 1954, all members of the Zoo staff who are over 50 years of age, or at least 45 years of age with 25 years of service, received a fourth week of vacation to mark the Zoo’s 25th anniversary.

That same year. the Zoo was used by a nurse to cheer up the sick children in the children’s hospital with a llama.

The Zoo experienced an educational innovation, the Hediger panels.

Zurich Zoo was the first zoo in Europe to have information display cases containing information on four areas

- the animal name in the national languages as well as in its scientific form

- the distribution map

- a photograph (in some species a coloured drawing) of the species

- a short text with special features of the animal described

The system of the Hediger panels has established itself in numerous zoos and has also proven itself.

Another important event under the leadership of Heini Hediger was the construction of the first free-flight hall, which can be regarded as a milestone in modern bird husbandry.

In 1955, with an exact number of 527,332 visitors, the mark of half a million zoo visitors per year was exceeded for the first time.

In 1960, the Zoo was recognized as a cultural institution with charitable motives and was thus exempt from taxes.

In 1961, Hediger presented an overall plan for enlarging the Zoo.

The new annexed areas were intended to create separate areas for cloven-hoofed and non-cloven-hoofed animals, which the Zoo director hoped would avoid another closure due to foot-and-mouth disease.

The implementation of the project failed for financial reasons.

In 1962, it was decided that supportive amounts of money would be paid by the city and canton in favour of the Zoo, which was justified by the scientific claim of the Zoo.

Three years later, the new Africa House opened with residents such as black rhinos, pygmy hippos and various African bird species, such as maggot choppers, cattle egrets or tokos.

The Africa House represented Hediger’s philosophy in an exemplary manner.

Different animal species were housed in the same enclosure, which also form a symbiosis in nature.

The decisive factor here was not the size, but the possibility of being able to live all the important behaviours, such as food intake and reproduction, in their own enclosure.

Hediger’s changes also improved the Zoo’s image.

From 1967 onwards, Heini Hediger and the senior zoo veterinarian passed on their newly acquired knowledge about the successful keeping of wild animals in the Zoo in evening courses.

At the end of his service, Hediger was honored by the city of Zürich with the Award for Cultural Services.

The concept of a modern zoo according to Hediger:

- The zoo is a recreational area for the city population and thus represents an emergency exit to nature.

- It is a source of information in the field of nature, especially zoology, and is therefore generally used for education.

- It operates nature conservation and protects endangered species and is therefore important as a refuge and breeding station.

- It is important for the zoo to participate in scientific research and, above all, to study the behaviour of animals more closely.

Hediger described a number of standard interaction distances used in one form or another between animals.

Two of these are flight distance and critical distance, used when animals of different species meet, whereas others are personal distance and social distance, observed during interactions between members of the same species.

Hediger’s biological social distance theories were used as a basis for Edward T. Hall’s 1966 anthropological social distance theories.

In the 1950s, psychologist Humphry Osmond developed the concept of socio-architecture hospital design, such as was used in the design of the Weyburn mental hospital in 1951, based partly on Hediger’s species-habitat work.

In 1942 Heini Hediger developed the science of wild animals kept in human care and published his concept of a new, special branch of biology, called “zoo biology”.

The main statement is that animals in zoos are not to be considered as “captives” but as “owners of property”, namely the territory of their enclosures.

They mark and defend this territory as they do in the natural environment and if the enclosures contain these elements which are of importance to them also in their natural environment, they have neither need nor desire to leave this property, but to the contrary, stay within it, even when they would have the opportunity to escape, or return to this “safe haven”, should they by accident have escaped.

He consequently emphasized that the quality of the enclosures (“furnishing”, structure) is equally, or even more important than quantity (space, dimensions) and substantiated this with observations in the natural habitat.

Among many other things he made clear that animals in the natural habitat do not need huge spaces, and all their needs can be satisfied within close range, that, in fact, animals do not move about for pleasure but to satisfy their needs.

Zoo biology therefore implies that the life of animals in their natural surroundings must be studied in order to provide them with appropriate keeping conditions in human care.

In animal husbandry, the aim of this concept — guided by the maxim “changing cages into territories” — was to meet the biological and ethological requirements of the exhibited animals.

Hediger’s publications influenced the keeping of wild animals in human care in particular also in the construction of enclosures and the planning of zoos.

In the 1950s, he began promoting the concept of training zoo animals to elicit biologically suitable behavior and to afford the animal exercise and mental occupation.

Further, he observed that in some cases training increased the opportunity for the zookeeper to give needed medical treatments to the animal.

He also referred to zoo animal training as “disciplined play”.

In the 1940s he defined the four main tasks of zoos:

- Recreation

- Education

- Research

- Conservation

In the 1960s, he defined the seven aspects of a zoological garden considering people, money, space, methods, administration, animals and research, in that order.

Thanks to Hediger, massive barriers are no longer used today, since symbolic borders are sufficient for most animal species.

The animals living in zoos today are limited by their accepted territory boundaries, which are also marked.

There is no complete freedom either in the zoo or in the wild, because there are limits in nature that are invisible to humans but exist for the animal species.

Hediger’s goal is to show the animals, as far as possible, in natural breeding groups, i.e. living together with their social partners, in an environment that is optimally geared to the well-being of the animals.

This concept is in stark contrast to the then customary keeping of individual animals in small cages, as was common in the menageries of the 19th century.

The advent of vaccinations made it much easier for Hediger to adopt an attitude in social organizations.

In order to avoid boredom and stereotypical behavior of captive wild animals, Hediger propagates the method of behavioural enrichment.

He reintroduced the new concept of zoo biology and dealt with such matters as food, causes of death, zoo architecture, the meaning of animal to man and man to animal, the exhibition value of animals, and the behavior of humans in zoos.

“Hunger and love can take only second place.

The satisfaction of hunger and sexual appetite can be postponed.

Not so escape from a dangerous enemy, and all animals, even the biggest and fiercest, have enemies.

As far as higher animals are concerned, escape must thus at any rate be considered as the most important behaviour biologically.“

A key behavioural characteristic of all pets is the lack of a tendency to flee.

The best dairy cow would be of no real use if she would not allow man to approach her and she would not agree to being milked either.

Almost all pets can be described as contact animals, because not only the flight distance but also the individual distance is missing, which means that they like to be touched.

One speaks of tameness when the lack of a tendency to flee is based on an individual loss.

Domestication as the reason for the lack of a tendency to flee is due to a genetic loss.

For humans, isn’t travel their escape?

According to Hediger, certain animals, like humans, move on roads, which means they always use the same path to get around.

It is noticeable that smaller animals often use the roads of larger animals and these often follow the human roads themselves.

Meandering is very characteristic of animal roads, because the geometric straight line is not biologically determined.

The width of the roads depends specifically on the animal species (bison: 30 cm; mouse: 3 cm).

In the zoo, it is noticeable that a very heavily used crossing runs directly along the enclosure or cage border, which can be explained by a considerable reduction in the territory area.

But even flying animals, such as birds and bats, keep moving in the same air routes.

In addition to guided tours and animal lectures, the zoo school offers workshops for school classes of all ages on various topics related to animals as well as nature and species protection.

The school animal shows, which were already held by the founder Walter Pischl, will continue to be offered in a contemporary form on request.

When ecology emerged as a matter of public interest in the 1970s, a few zoos began to consider making conservation their central role, with Gerald Durrell of the Jersey Zoo, George Rabb of Brookfield Zoo, and William Conway of the Bronx Zoo (Wildlife Conservation Society) leading the discussion.

From then on, zoo professionals became increasingly aware of the need to engage themselves in conservation programs.

The American Zoo Association soon said that conservation was its highest priority.

In order to stress conservation issues, many large zoos stopped the practice of having animals perform tricks for visitors.

The Detroit Zoo, for example, stopped its elephant show in 1969, and its chimpanzee show in 1983, acknowledging that the trainers had probably abused the animals to get them to perform.

Mass destruction of wildlife habitat has yet to cease all over the world and many species such as elephants, big cats, penguins, tropical birds, primates, rhinos, exotic reptiles, and many others are in danger of dying out.

Many of today’s zoos hope to stop or slow the decline of many endangered species and see their primary purpose as breeding endangered species in captivity and reintroducing them into the wild.

Modern zoos also aim to help teach visitors the importance on animal conservation, often through letting visitors witness the animals firsthand.

Some critics and the majority of animal rights activists say that zoos, no matter what their intentions are, or how noble they are, are immoral and serve as nothing but to fulfill human leisure at the expense of the animals (which is an opinion that has spread over the years).

However, zoo advocates argue that their efforts make a difference in wildlife conservation and education.

Zoo animals live in enclosures that often attempt to replicate their natural habitats or behavioral patterns, for the benefit of both the animals and visitors.

Nocturnal animals are often housed in buildings with a reversed light-dark cycle, i.e. only dim white or red lights are on during the day so the animals are active during visitor hours, and brighter lights on at night when the animals sleep.

Special climate conditions may be created for animals living in extreme environments, such as penguins.

Special enclosures for birds, mammals, insects, reptiles, fish and other aquatic life forms have also been developed.

Some zoos have walk-through exhibits where visitors enter enclosures of non-aggressive species, such as lemurs, marmosets, birds, lizards and turtles.

Visitors are asked to keep to paths and avoid showing or eating foods that the animals might snatch.

Some zoos keep animals in larger, outdoor enclosures, confining them with moats and fences, rather than in cages.

Safari parks, also known as zoo parks and lion farms, allow visitors to drive through them and come in close proximity to the animals.

Sometimes, visitors are able to feed animals through the car windows.

The first safari park was Whipsnade Park in Bedfordshire, England, opened by the Zoological Society of London in 1931 which today (2014) covers 600 acres (2.4 km2).

Since the early 1970s, an 1,800 acre (7 km2) park in the San Pasqual Valley near San Diego has featured the San Diego Zoo Safari Park, run by the Zoological Society of San Diego.

One of two state-supported zoo parks in North Carolina is the 2,000-acre (8.1 km2) North Carolina Zoo in Asheboro.

The 500-acre (2.0 km2) Werribee Open Range Zoo in Melbourne, Australia, displays animals living in an artificial savannah.

The only safari-type park I have visited was the aforementioned Night Safari in Singapore.

The Night Safari, Singapore is the world’s first nocturnal zoo.

Unlike traditional nocturnal houses, which reverse the day-night cycle of animals so they will be active by day, the Night Safari is an entire open-air zoo set in a humid tropical forest that is only open at night.

It is divided into six geographical zones, which can be explored either on foot via four walking trails, or by tram.

The animals of the Night Safari, ranging from axis deer and African buffalo to Indian rhinoceros and pangolins to lions and Asian elephants, are made visible by lighting that resembles moonlight.

Although it is brighter than full moonlight by a few orders of magnitude, it is dim enough not to disturb nocturnal and crepuscular (active primarily at twilight) animals’ behaviour.

The naturalistic enclosures simulate the animals’ native habitat.

Animals are separated from visitors with natural barriers, rather than caged.

Instead of vertical prison-like cages, cattle grids were laid all over the park to prevent hoofed animals from moving one habitat to another.

These are grille-like metal sheets with gaps wide enough for animals’ legs to go through.

Moats were designed to look like streams and rivers to enable animals to be put on show in open areas, and hot wires were designed to look like twigs to keep animals away from the boundaries of their enclosures.

The tram takes visitors across the whole park, allowing visitors to view most of the park’s larger animals.

Animals on display include:

- Himalayan tahrs

- bharals

- markhor

- greater flamingos

- striped hyenas

- Asiatic lions

- sloth bears

- Indian rhinoceros

- axis deer

- Eld’s deer

- Cape buffalo

- spotted hyenas

- hippopotamus

- white lions

- Malayan tapirs

- dholes

- Bornean bearded pigs

- Asian elephants

- sambar deer

- Asian black bears

The Fishing Cat Trail features a variety of nocturnal animals mostly from Asia and South America such as:

- the fishing cat

- binturong

- spectacled owls

- southern three-banded armadillo

- maned wolf

- giant anteater

- Indian muntjac

- Asian small-clawed otter

- gharial

- spotted whistling ducks

- little pied cormorants

The Leopard Trail houses a variety of nocturnal animals from the rainforests of Asia like:

- clouded leopards

- a large flying fox walkthrough aviary

- a habitat for animals native to Singapore like:

- leopard cats

- Sunda pangolins

- other habitats for:

- greater hog badgers

- Northern Luzon giant cloud rats

- Sunda slow loris

- Senegal bushbabies

- fossa

- porcupines

- owls

The Asiatic lions are also visible from a boardwalk on the edge of the trail.

Along the East Lodge Trail are habitats for:

- Malayan tigers

- red river hogs

- North Sulawesi babirusa

- bongos

- aardvarks

Opening in 2012, the Wallaby Trail features a walkthrough habitat for red-necked wallabies and also has enclosures for woylies, common brushtail possums and morepork.

The Trail also has a large man-made cave called the Naracoorte Cave, a reconstruction of the Naracoorte Caves National Park, which has several indigenous paintings and holds invertebrates and reptiles.

A public aquarium (plural: public aquaria or public aquariums) is the aquatic counterpart of a zoo, which houses living aquatic animal and plant specimens for public viewing.

Most public aquariums feature tanks larger than those kept by home aquarists, as well as smaller tanks.

Since the first public aquariums were built in the mid-19th century, they have become popular and their numbers have increased.

Most modern accredited aquariums stress conservation issues and educating the public.

The first public aquarium was opened at the London Zoo in 1853.

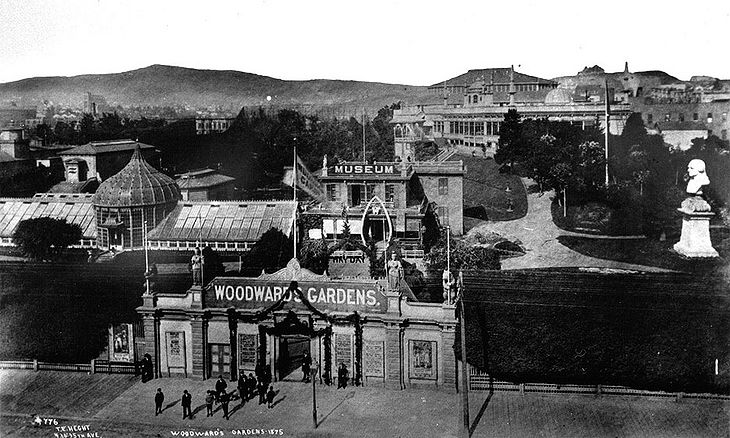

This was followed by the opening of public aquaria in continental Europe (e.g. Paris in 1859, Hamburg in 1864, Berlin in 1869, and Brighton in 1872) and the United States (e.g. Boston in 1859, Washington in 1873, San Francisco Woodward’s Gardens in 1873, and the New York Aquarium at Battery Park in 1896).

The aquariums I have visited:

- Great Aquarium, Saint Malo, France

- Sea Life Centre, Konstanz, Germany

- Aquarium of Genoa, Italy

- Lisbon Oceanarium, Portugal

- Aquarium Donostia-San Sebastián, Spain

- Cosmocaixa, Barcelona, Spain

I am generally not as enthusiastic about aquariums as I am about zoos.

Roadside zoos are found throughout North America, particularly in remote locations.

They are often small, for-profit zoos, often intended to attract visitors to some other facility, such as a gas station.

The animals may be trained to perform tricks, and visitors are able to get closer to them than in larger zoos.

Since they are sometimes less regulated, roadside zoos are often subject to accusations of neglect and cruelty.

In June 2014 the Animal Legal Defense Fund (ALDF) filed a lawsuit against the Iowa-based roadside Cricket Hollow Zoo for violating the Endangered Species Act by failing to provide proper care for its animals.

Since filing the lawsuit, ALDF has obtained records from investigations conducted by the USDA’s Animal and Plant Health Inspection Services.

These records show that the zoo is also violating the Animal Welfare Act.

Above: Cricket Hollow Zoo, Manchester, Iowa

In modern, well-regulated zoos, breeding is controlled to maintain a self-sustaining, global captive population.

This is not the case in some less well-regulated zoos, often based in poorer regions.

Overall “stock turnover” of animals during a year in a select group of poor zoos was reported as 20% – 25%, with 75% of wild caught apes dying in captivity within the first 20 months.

The authors of the report stated that before successful breeding programs, the high mortality rate was the reason for the “massive scale of importations“.

One two-year study indicated that of 19,361 mammals that left accredited zoos in the US between 1992 and 1998, 7,420 (38%) went to dealers, auctions, hunting ranches, unaccredited zoos and individuals, and game farms.

A petting zoo (also called a children’s zoo, children’s farm, or petting farm) features a combination of domesticated animals and some wild species that are docile enough to touch and feed.

In addition to independent petting zoos, many general zoos contain a petting zoo.

Most petting zoos are designed to provide only relatively placid, herbivorous (plants only) domesticated animals, such as sheep, goats, pigs, rabbits or ponies, to feed and interact physically with safety.

This is in contrast to the usual zoo experience, where normally wild animals are viewed from behind safe enclosures where no contact is possible.

A few provide wild species (such as pythons or big cat cubs) to interact with, but these are rare and usually found outside Western nations.

To ensure the animals’ health, the food is supplied by the zoo, either from vending machines or a kiosk nearby.

Food often fed to animals includes grass and crackers and also in selected feeding areas hay is a common food.

Such feeding is an exception to the usual rule about not feeding animals.

Touching animals can result in the transmission of diseases between animals and humans (zoonosis) so it is recommended that people should thoroughly wash their hands before and after touching the animals.

There have been several outbreaks of E. coli, etc.

(Escherichia coli, also known as E. coli, is a kind of bacteria that is commonly found in the lower intestine of warm-blooded organisms.

Most E. coli strains are harmless, but some can cause serious food poisoning in their hosts, and are occasionally responsible for food contamination incidents that prompt product recalls.

The harmless strains are part of the normal microbiota of the gut and can benefit their hosts by producing vitamin K2 and preventing colonisation of the intestine with pathogenic bacteria, having a mutualistic relationship.

E. coli is expelled into the environment within fecal matter.

The bacterium grows massively in fresh fecal matter under aerobic conditions for three days, but its numbers decline slowly afterwards.)

I have visited petting zoos before, of course.

One I have frequently visited is the one in Seeburgpark (lake castle park), Kreuzlingen, Switzerland.

An animal theme park is a combination of an amusement park and a zoo, mainly for entertaining and commercial purposes.

Marine mammal parks, such as Sea World and Marineland, are more elaborate dolphinariums keeping whales, and containing additional entertainment attractions.

Another kind of animal theme park contains more entertainment and amusement elements than the classical zoo, such as stage shows, roller coasters, and mythical creatures.

Some examples are:

- Busch Gardens Tampa Bay, Tampa, Florida

- Disney’s Animal Kingdom, Bay Lake, (near Orlando), Florida

- Gatorland, Orlando, Florida

- Flamingo Land, North Yorkshire, England

- Six Flags Discovery Kingdom, Vallejo, California

The one park that sticks in my mind that I have visited and that claims to be an animal theme park is Connyland, Lipperswil, between Frauenfeld and Kreuzlingen, Canton Thurgau, Switzerland.

The amusement park, which opened in 1983, is best known for its former dolphinarium and its Patagonian sea lions.

.

By 2000, most animals being displayed in zoos were the offspring of other zoo animals.

This trend, however was and still is somewhat species-specific.

When animals are transferred between zoos, they usually spend time in quarantine, and are given time to acclimatize to their new enclosures which are often designed to mimic their natural environment.

For example, some species of penguins may require refrigerated enclosures.

Guidelines on necessary care for such animals is published in the International Zoo Yearbook (published by the Zoological Society of London (ZSL), a charity devoted to the worldwide conservation of animals and their habitats).

Especially in large animals, a limited number of spaces are available in zoos.

As a consequence, various management tools are used to preserve the space for the genetically most important individuals and to reduce the risk of inbreeding.

Management of animal populations is typically through international organizations, such as the Association of Zoos and Aquariums (AZA) and the European Association of Zoos and Aquaria (EAZA).

Zoos have several different ways of managing the animal populations, such as moves between zoos, contraception, sale of excess animals and euthanization (culling).

Contraception can be an effective way to limit a population’s breeding.

However it may also have health repercussions and can be difficult or even impossible to reverse in some animals.

Additionally, some species may lose their reproductive capability entirely if prevented from breeding for a period (whether through contraceptives or isolation), but further study is needed on the subject.

Sale of surplus animals from zoos was once common and in some cases animals have ended up in substandard facilities.

In recent decades the practice of selling animals from certified zoos has declined.

A large number of animals are culled each year in zoos, but this is controversial.

A highly publicized culling as part of population management was that of a healthy giraffe at Copenhagen Zoo in 2014.

The Zoo argued that its genes already were well-represented in captivity, making the giraffe unsuitable for future breeding.

There were offers to adopt it and an online petition to save it had many thousand signatories, but the culling proceeded.

Although zoos in some countries have been open about culling, the controversy of the subject and pressure from the public has resulted in others being closed.

This stands in contrast to most zoos publicly announcing animal births.

Furthermore, while many zoos are willing to cull smaller and/or low-profile animals, fewer are willing to do it with larger high-profile species.

The position of most modern zoos in Australasia, Asia, Europe and North America, particularly those with scientific societies, is that they display wild animals primarily for the conservation of endangered species, as well as for research purposes and education, and secondarily for the entertainment of visitors.

The Zoological Society of London states in its charter that its aim is “the advancement of zoology and animal physiology and the introduction of new and curious subjects of the animal kingdom“.

It maintains two research institutes, the Nuffield Institute of Comparative Medicine and the Wellcome Institute of Comparative Physiology.

In the US, the Penrose Research Laboratory of the Philadelphia Zoo focuses on the study of comparative pathology (the study of diseases and their causes).

The World Association of Zoos and Aquariums produced its first conservation strategy in 1993, and in November 2004, it adopted a new strategy that sets out the aims and mission of zoological gardens of the 21st century.

When studying behaviour of captive animals, several things should however be taken into account before drawing conclusions about wild populations.

Including that captive populations are often smaller than wild ones and that the space available to each animal is often less than in the wild.

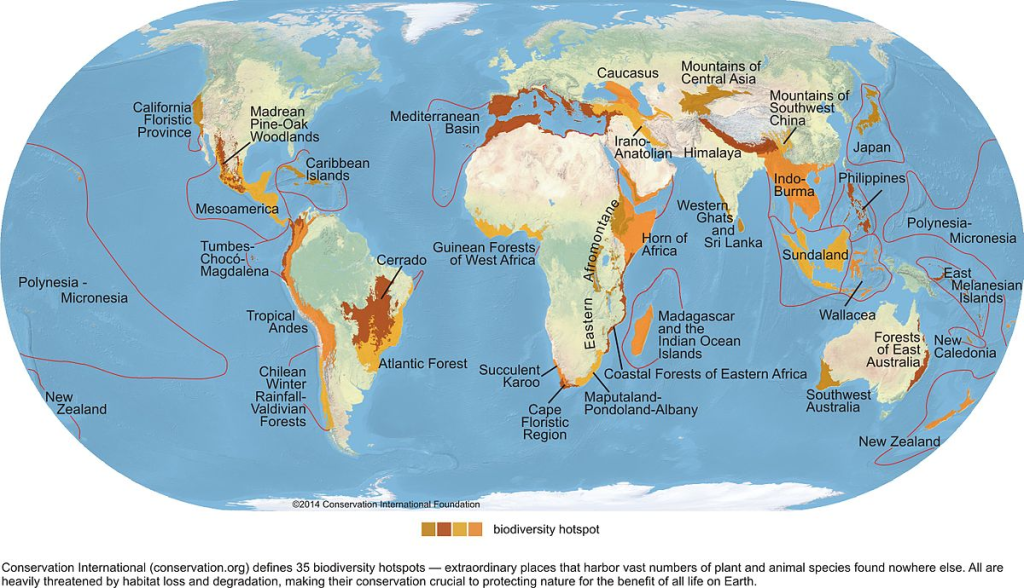

Conservation programs all over the world fight to protect species from going extinct, but many conservation programs are underfunded and under-represented.

Conservation programs can struggle to fight bigger issues like habitat loss and illness.

It often takes a lot of funding and long time periods to rebuild degraded habitats, both of which are scarce in conservation efforts.

The current state of conservation programs cannot rely solely on situ (on-site conservation) plans alone, ex situ (off-site conservation) may therefore provide a suitable alternative.

Off-site conservation relies on zoos, national parks, or other care facilities to support the rehabilitation of the animals and their populations.

Zoos benefit conservation by providing suitable habitats and care to endangered animals.

When properly regulated, they present a safe, clean environment for the animals to increase populations sizes.

A study on amphibian conservation and zoos addressed these problems by writing:

“Whilst addressing in situ threats, particularly habitat loss, degradation and fragmentation, is of primary importance.

For many amphibian species in situ conservation alone will not be enough, especially in light of current un-mitigatable threats that can impact populations very rapidly such as chytridiomycosis [an infectious fungal disease].

Ex situ programmes can complement in situ activities in a number of ways including maintaining genetically and demographically viable populations while threats are either better understood or mitigated in the wild.”

The breeding of endangered species is coordinated by cooperative breeding programmes containing international studbooks and coordinators, who evaluate the roles of individual animals and institutions from a global or regional perspective.

There are regional programmes all over the world for the conservation of endangered species.

In Africa, conservation is handled by the African Preservation Program (APP), in the US and Canada by Species Survival Plan, in Australasia by the Australasian Species Management Program, in Europe by the European Endangered Species Program, and in Japan, South Asia, and South East Asia, by the Japanese Association of Zoos and Aquariums, the South Asian Zoo Association for Regional Cooperation, and the South East Asian Zoo Association.

Above: Logo of the South Asian Zoo Association for Regional Cooperation

Besides conservation of captive species, large zoos may form a suitable environment for wild native animals such as herons to live in or visit.

A colony of black crowned night herons has regularly summered at the National Zoo in Washington DC for more than a century.

Some zoos may provide information to visitors on wild animals visiting or living in the zoo, or encourage them by directing them to specific feeding or breeding platforms.

The welfare of zoo animals varies widely.

Many zoos work to improve their animal enclosures and make it fit the animals’ needs, but constraints such as size and expense can complicate this.

The type of enclosure and the husbandry are of great importance in determining the welfare of animals.

Substandard enclosures can lead to decreased lifespans, caused by factors as human diseases, unsafe materials in the cages and possible escape attempts.

However, when zoos take time to think about the animal’s welfare, zoos can become a place of refuge.

There are animals that are injured in the wild and are unable to survive on their own, but in the zoos they can live out the rest of their lives healthy and happy.

In recent years, some zoos have chosen to move out some larger animals because they do not have the space available to provide an adequate enclosure for them.

An issue with animal welfare in zoos is that best animal husbandry practices are often not completely known.

Especially for species that are only kept in a small number of zoos.

To solve this, organizations, like the EAZA and the AZA, have begun to develop husbandry manuals.

Many modern zoos attempt to improve animal welfare by providing more space and behavioural enrichments.

This often involves housing the animals in naturalistic enclosures that allow the animals to express more of their natural behaviours, such as roaming and foraging.

Whilst many zoos have been working hard on this change, in some zoos, some enclosures still remain barren concrete enclosures or other minimally enriched cages.

Sometimes animals are unable to perform certain behaviors in zoos, like seasonal migration or traveling over large distances.

Whether these behaviours are necessary for good welfare, however, is unclear.

Some behaviours are seen as essential for an animal’s welfare whilst others aren’t.

It is, however, shown that even in limited spaces, certain natural behaviours can still be performed.

A study in 2014 for example found that Asian elephants in zoos covered similar or higher walking distances then sedentary wild populations.

Migration in the wild can also be related to food scarcity or other unfavourable environmental problems.

However, a proper zoo enclosure never runs out of food or water, and in case of unfavourable temperatures or weather animals are provided with shelter.

Heini Hediger was convinced that animals have “a kind of consciousness“.

It is unthinkable for him not to start from the correctness of this point of view.

In the following, consciousness is understood as knowledge about oneself.

To support his results, Hediger cited an African bird, the honey stalker, as an example, which likes to eat bee larvae.

In the normal case, the bird leads a honey badger to a beehive.

The badger destroys the honeycomb and eats the honey.

The rest is available to the honey stalker.

But if a human honey collector takes on the task of the badger and hits the tree with a machete, the bird will fly over and lead the human to the nearest beehive.

For Hediger, this behavior can hardly be explained without the idea of an animal consciousness.

In addition, he underscores the correctness of his ideas with an example that ascribes humour or at least a kind of “Schadenfreude” to certain animals.

A juvenile steppe baboon has been observed repeatedly climbing down from the acacia tree on which it was sitting and under which a pack of wild dogs were resting, jumping around in front of the pack, and finally climbing up the tree again.

This form of “annoying” can hardly be understood without a simple form of empathizing with others, combined with one’s own intention.

Another evidence of the consciousness of certain animals that Hediger shows is the consciousness of one’s own size, which is the most primitive, but also the most important form of self-awareness.

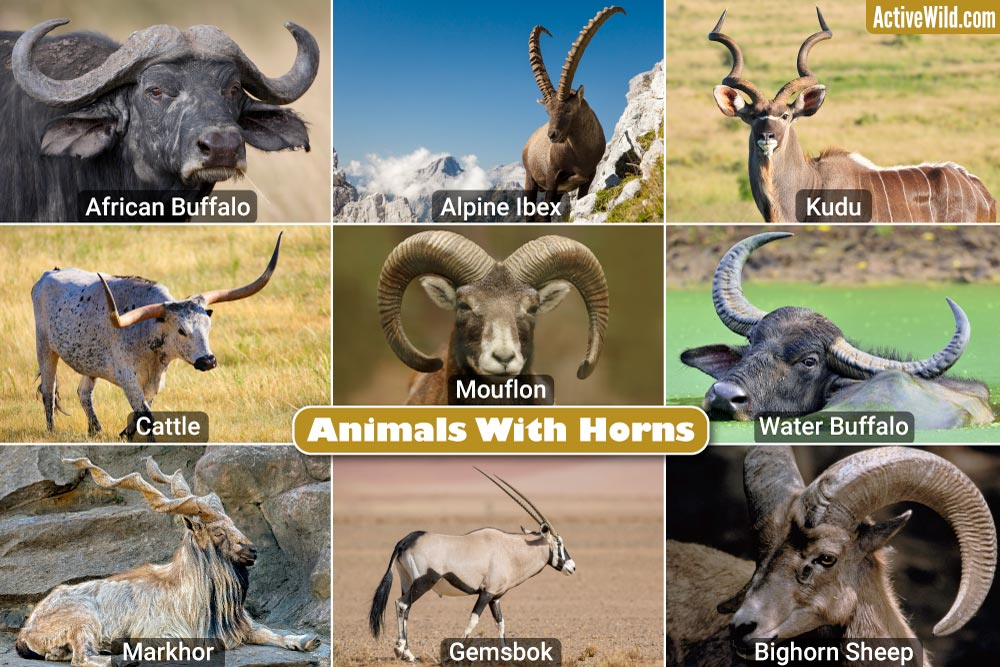

Horned animals in zoos often force their heads through very narrow meshes to get food.

It is difficult for humans to understand the elegance with which the animals manage to withdraw their heads with the long appendages from the opening.

The conscious use of an animal’s shadow also allows conclusions to be drawn about its consciousness.

For example, a Chapman mare, who was considered a model mother, positioned her body in such a way that her shadow fell on the foal resting on the ground in extreme summer sunshine.

Animals in zoos can exhibit behaviors that are abnormal in their frequency, intensity, or would not normally be part of their behavioural repertoire.

Whilst these types of behaviours can be a sign of bad welfare and stress, this isn’t necessarily the case.

Other measurements or behavioural research is advised before determining whether an animal performing stereotypical behaviour is living in bad welfare or not.

Examples of stereotypical behaviors are pacing, head-bobbing, obsessive grooming and feather-plucking.

A study examining data collected over four decades found that polar bears, lions, tigers and cheetahs can display stereotypical behaviors in many older exhibits.

However they also noted that in more modern naturalistic exhibits, these behaviors could completely disappear.

Elephants have also been recorded displaying stereotypical behaviours in the form of swaying back and forth, trunk swaying or route tracing.

This has been observed in 54% of individuals in UK zoos.

However, it has been shown that modern facilities and modern husbandry can greatly decrease or even entirely remove abnormal behaviours.

A study of a group of elephants in Planckendael (Belgium) showed that the older wild-caught animals displayed many stereotypical behaviours.

These elephants had spent part of their lives either in a circus or in other substandard enclosures.

On the other hand, the elephants born in the modern facilities that had lived in a herd their whole life barely displayed any stereotypical behaviors at all.

The life history of an animal is thus extremely important when analyzing the causes of stereotypical behaviour, as this can be a historical relict instead of a result of present-day husbandry.

The influence on a zoological environment on animal’s longevity is not straightforward.

A study of 50 mammal species found that 84% of them actually lived longer in zoos than they would in the wild on average.

On the other hand, some research claims that elephants in Japanese zoos would live shorter than their wild counterparts at just 17 years.

This has been refuted by other studies however.

It is important to acknowledge here that studies might not yet fully represent recent improvements in husbandry.

For example, studies show that captive-bred elephants already have a lower mortality risk then wild-caught ones.

Climatic conditions can make it difficult to keep some animals in zoos in some locations.

For example, the Alaska Zoo had an elephant named Maggie.

She was housed in a small, indoor enclosure because the outdoor temperature was too low.

Some critics and many animal rights activists claim that zoo animals are treated as voyeuristic objects, rather than living creatures, and often suffer due to the transition from being free and wild to captivity.

However, ever since imports of wild-caught animals became more regulated by organizations like CITES and national laws zoos have started sustaining their populations via breeding.

This change started around the 1970s.

Many co-operations in the form of breeding programs have been set up since, for both common and endangered species.

(CITES (shorter name for the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora, also known as the Washington Convention) is a multilateral treaty to protect endangered plants and animals.

It was drafted as a result of a resolution adopted in 1963 at a meeting of members of the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN).

The Convention was opened for signature in 1973.

CITES entered into force on 1 July 1975.

Its aim is to ensure that international trade in specimens of wild animals and plants does not threaten the survival of the species in the wild.

It accords varying degrees of protection to more than 35,000 species of animals and plants.

In order to ensure that the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) was not violated, the Secretariat of GATT was consulted during the drafting process.)

In some countries, feeding live vertebrates to zoo animals is illegal under most circumstances.

The UK Animal Welfare Act of 2006, for example, states that prey must be killed for feeding, unless this threatens the health of the predator.

Some zoos had already adopted such practices prior to the implementation of such policies.

London Zoo, for example, stopped feeding live vertebrates in the 20th century, long before the Animal Welfare Act.

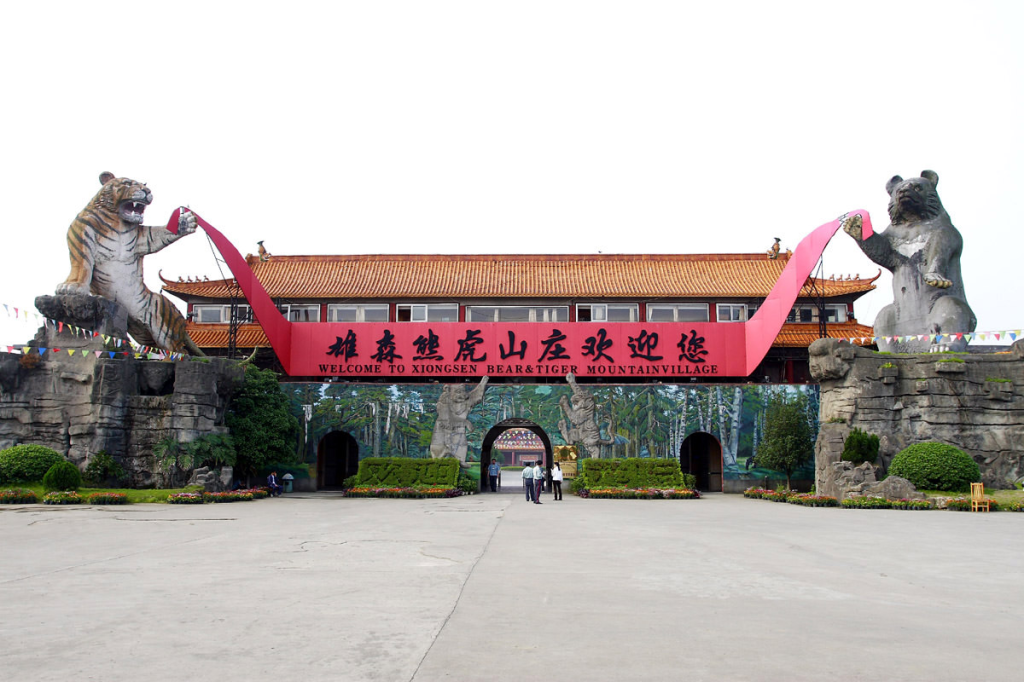

Despite being illegal in China, some zoos have been found to still feed live vertebrates to their predators.

In some parks, like Xiongsen Bear and Tiger Mountain Village, live chickens and other livestock were found to be thrown into the enclosures of tigers and other predators.

Live cows and pigs are thrown to tigers to amuse visitors.

Other Chinese parks, like Shenzhen Safari Park, have already stopped this practice after facing heavy criticism.

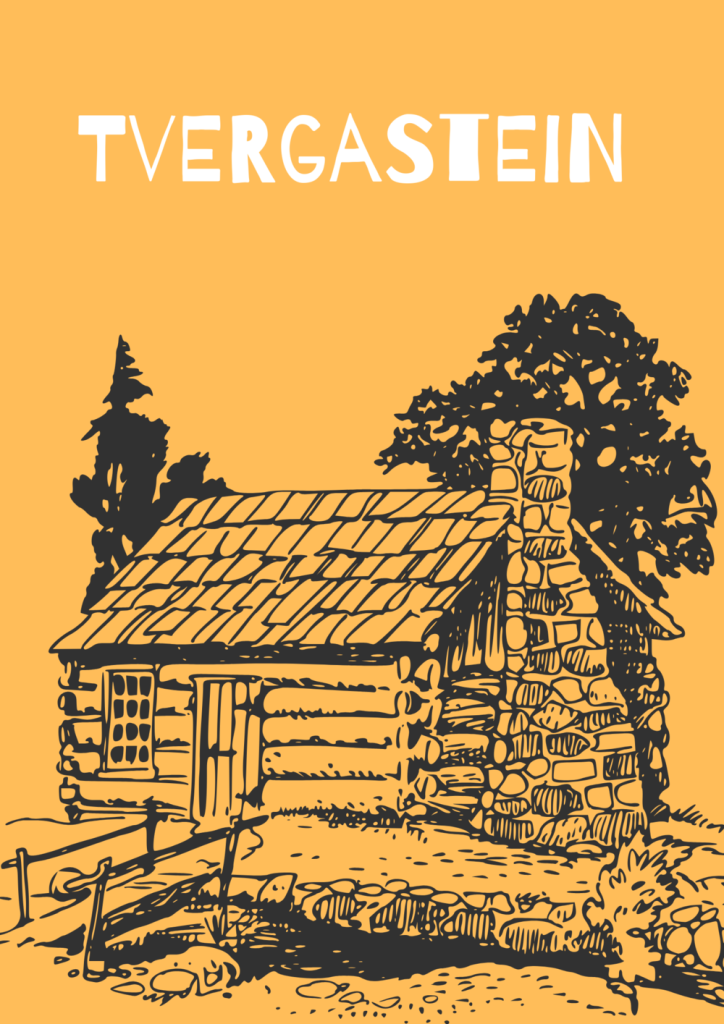

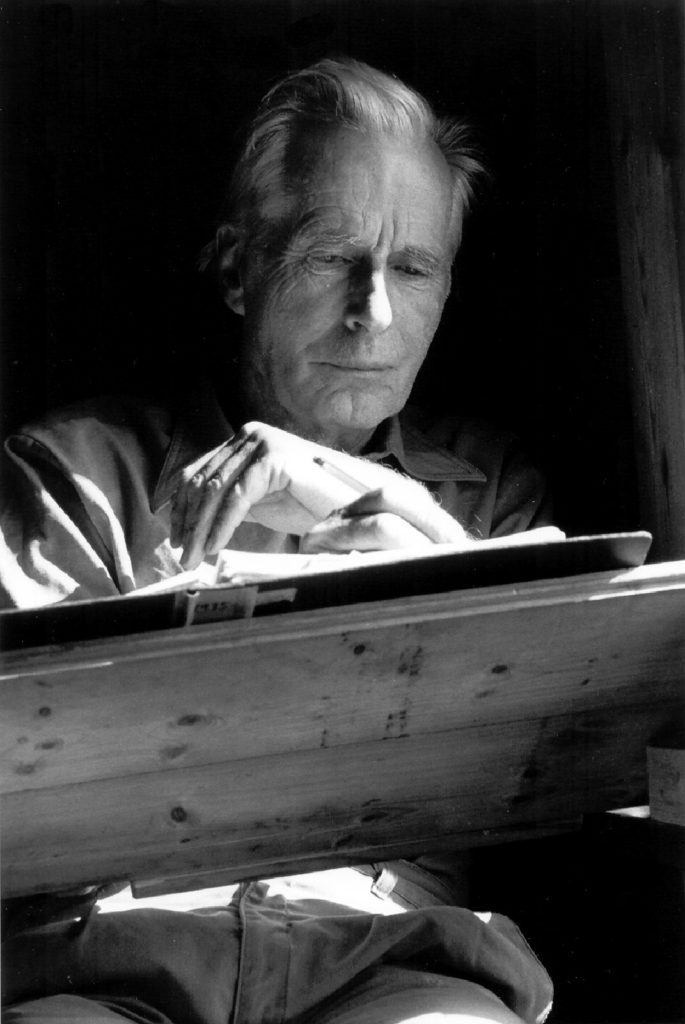

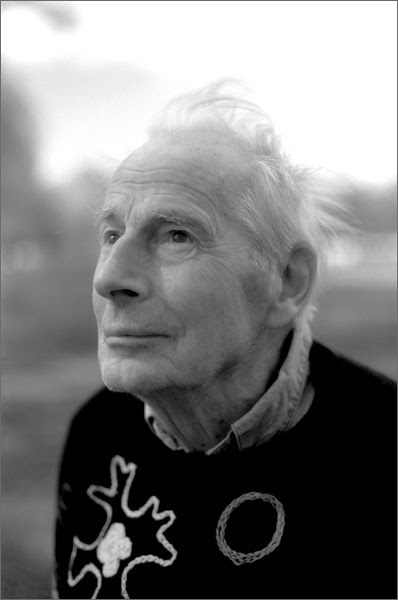

From childhood until his death, Arne Naess spent summers and holidays exploring the mountains east of Bergen, Norway.

In the late 1930s, when he was in his 20s, Naess built a simple cabin on a remote mountain perch called Tvergastein – so remote that it took him 62 trips with a horse to carry up the timbers.

At 1,500 metres, it was the highest private cabin in Scandinavia and required considerable hiking, snowshoeing or skiing to be reached.

Despite a cosmopolitan life of global activism, research, writing and teaching, Naess spent much of his adult life in his mountain hideaway, exploring the local flora and fauna, and reading Plato, Aristotle, Spinoza and Gandhi.

He sought to leave a small footprint not only on his beloved mountain but also on the planet Earth – so he ate only vegetables, possessed only necessities and often lived in his cabin without electricity or plumbing and with very little heat.

Why would a distinguished philosopher withdraw from the modern world and even largely from human society?

Naess had fallen in love with his mountain perch.

This love led him to identify himself with every living creature, from fleas to human beings.

He even considered changing his own name to Arne Tvergastein.

We never know what we truly have loved until we lose it.

Edmund Burke pioneered conservative political thought in the wake of the French Revolution.

There were no “conservatives” until all moral, religious, social and political traditions came under attack from the revolutionaries of 1789.

Similarly, there were no environmentalists, ecologists or conservationists until the Industrial Revolution threatened to destroy the remaining wilderness and even familiar rural landscapes.

Just as political conservatives see political change in terms of what is being lost, so many conservationists see economic change in terms of the loss of natural habitats.

No one has been more eloquent or influential in mourning what we have lost to modern commerce, industry and technology than Naess, who once chained himself to a waterfall so that it would not be dammed up.

Naess is best known for his concept of “deep ecology“.

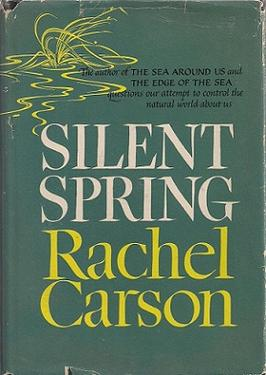

Næss cited Rachel Carson’s 1962 book Silent Spring as being a key influence in his vision of deep ecology.

Næss combined his ecological vision with Gandhian non-violence and on several occasions participated in direct action.

According to him, most environmentalists aim to promote merely human values, by reducing pollution to protect human health, conserving resources to protect future consumption and preserving a bit of wilderness for recreation.

All of this “shallow ecology“, said Naess, ignores the inherent value of nature quite apart from its effects on human welfare.

Deep ecology holds that not only human beings but all living creatures have a right to live and to flourish.

Naess was appalled by what he saw as the arrogance of human beings who treat the whole of the natural world as nothing more than a woodpile to be used, destroyed or wasted for our own convenience.

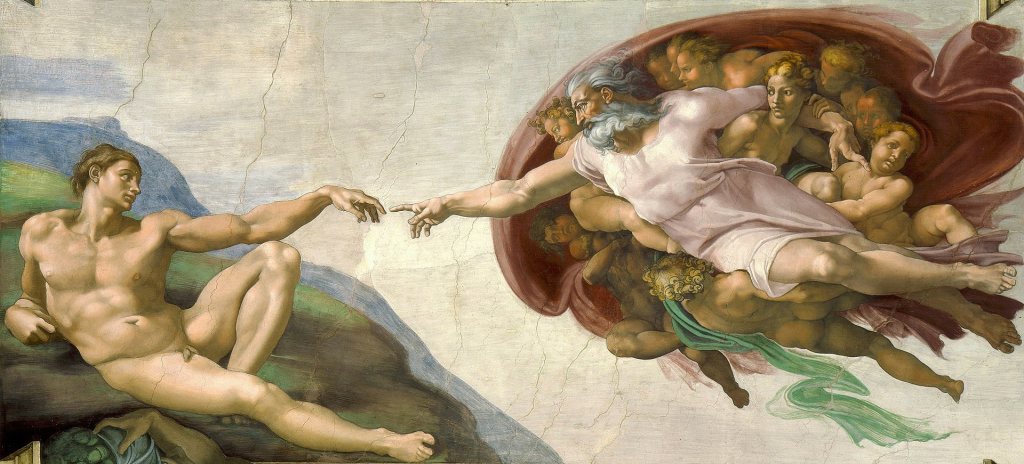

In the Christian Bible, God gives Adam “dominion” over nature.

Naess rejected this ideal of human domination or even stewardship over the natural world.

As if humans could possibly know enough to “manage” the infinite complexity of nature!

According to Naess, every significant human attempt to manage nature has backfired, revealing our arrogance and ignorance.

Many large dams, for instance, are now being modified or dismantled because of the unforeseen ecological disasters they have created.

Industrial agriculture has left deserts and dust storms in its wake.

Naess wanted human beings to be good citizens of the Earth, not its masters.

As good citizens of planet Earth, said Naess, we ought to be concerned not just with our own parochial human interests but also with the common good of the whole of nature.

What is that common good?

Naess followed the 17th century philosopher Benedict Spinoza in arguing that nature is just another word for God.

Instead of locating spiritual or divine realities apart from or above nature, Naess believed that divinity is just another aspect of nature.

According to Spinoza, the highest human good is the intellectual love of God, which means, said Naess, the loving appreciation of the infinite diversity of life.

Every creature, said Spinoza, including human beings, strives to preserve itself and to actualize all of its powers.

Naess insisted that the common good of nature is the self-realization of every living organism.

Human self-realization uniquely culminates in the capacity to contemplate and to love the totality of nature, of which we are only one small part.

What this means, said Naess, is that human beings approach the divine not by turning away from nature but rather by finding our true home within it.

Although human beings have always attempted to leave our natural homes by voyages to new continents and now even to new planets, Naess insisted that no one can be truly happy except in intimate relation with a particular natural setting.

Thus, Naess rejected modern ideals of globalization, cosmopolitanism and tourism, let alone space travel.

He even fought to keep Norway out of the European Union.

He implicitly wanted everyone to follow his own example of a lifelong intimate relation to a particular natural place.

Naess’ theory of deep ecology and his worship of non-human nature have led other ecologists to call him a mystic, a misanthrope, a fascist and even a Nazi – despite his heroic service resisting the German occupation of Norway.

Because human beings pose a unique threat to pristine nature and perhaps even to the future of life on Earth, some “deep ecologists” are indeed misanthropic.

They argue that we need more disease, war and poverty to reduce human numbers if the natural world is going to survive.

Naess himself agreed that respect for the common good of nature requires a massive reduction in human population to a level of about 100 million, but before Naess became an ecologist he was a disciple of Gandhi’s philosophy of non-violence.

Gandhi, who tolerated poisonous snakes, spiders and scorpions within his own home, extended the principles of non-violence to the whole of nature.

Naess similarly rejected any use of force or coercion to protect nature.

He wanted to reduce human numbers by voluntary family planning.

Despite the radical or even violent implications of his own deep ecology and the malicious rhetoric heaped upon him, Naess was the most peace-loving of activists.

He never once resorted to verbal polemics or abuse.

Instead, he always sought respectful engagement and common ground with his opponents.

Everyone who ever met him agreed that he embodied the peace and goodwill that he sought to bring about in the world.

As a young man, Naess was traumatized by the experience of looking through a microscope and observing a flea that had jumped into a bath of acid.

Viewing with horror the struggle, the suffering and the death agony of this flea, Naess became a lifelong vegetarian.

His empathetic identification with the suffering flea became a cornerstone of his deep ecology.

Instead of asking human beings to sacrifice our interests on behalf of other creatures, Naess asked us to identify with other creatures, to expand our own “selves” to include the whole of nature.

Through this widening of the self, the protection of nature becomes a kind of enlightened self-interest rather than an altruistic self-sacrifice.

Although he occasionally used the language of rights and duties, Naess much preferred to appeal to beauty and joy.

He did sometimes refer to the “right to life” of every creature, implying our “duty” not to kill them.

He extended Immanuel Kant’s famous imperative “never to treat a person as a mere means but always also as an end” to our treatment of all living organisms.

However, in general, Naess was not interested in any kind of ethics, which he viewed as little more than moralistic aggression.

He believed that human beings are motivated less by ethical duties than by their understanding of the world.

If we came to see ourselves as just one part of an immense web of life, if we came to see ourselves in nature rather than above it, if we learned to appreciate the complexity and beauty of pristine ecosystems, then we would protect nature out of a feeling of joy rather than a sense of duty.

As a Gandhian pacifist, Naess was reluctant to impose moral, let alone legal, duties on other human beings.

He preferred to teach by his own example of loving tenderness towards all living creatures, great and small.

Hence, his rules about killing always include exceptions:

“Never kill another living creature unless you must in order to survive.”

He condemns killing for sport but not from hunger.

Although he rejects any explicit ranking of organisms, he does implicitly privilege human life.

Naess is often described or denigrated as a “mystic“.

He did not think that language, let alone philosophical argument, could capture our primordial “awe” in relation to nature.

Ultimately, he was a spiritual thinker who claimed that the human wonder before nature must be cultivated before the elaboration of any ecological ethics.

Naess himself drew upon Spinoza’s pantheism, Buddhism and Gandhian Hinduism in his own spirituality of nature, but he thought that a proper spiritual response to nature could also be found in many other religious traditions.

“The objective of the state is freedom”

The word “nature” evokes very different images in different minds, just as the word “God” does.

Nature can connote a nurturing mother, the cycle of life and relations of interdependence – or nature can connote the struggle for survival, predators and prey, and cycles of extinction.

Nature for Naess was ultimately a peaceable kingdom of mutual co-existence and harmony, where, in the biblical vision, “the lion lies down with the lamb“.

Human beings alone, he suggested, are unnatural:

Our overweening arrogance, our out-of-control fertility and our destructive intelligence pose a unique threat to the harmony of nature.

Nature was a garden of paradise until man arrived and overturned the divine order.

Unless human beings return to their proper place as but one creature among infinitely many, nature will be destroyed.

Yet, from another, more Darwinian point of view, nature is not a place of peace or harmony at all:

Every creature is locked into a struggle for survival.

Every creature produces too many offspring.

Every creature kills or is killed.

Natural history is replete with starvation, death by exposure, relentless predation and extinction.

By some accident of random genetic mutation, human beings developed a uniquely powerful combination of intelligence and dexterity, permitting us to become the top predator.

In this view, human culture, technology and urbanization are natural adaptations to our ecological niche, permitting us to dominate and subdue all other organisms.

Did human beings ever live in harmony with nature?

Naess and other ecologists have claimed that prehistoric and contemporary hunter-gatherers were able to co-exist with nature, but the fossil record suggests otherwise.

As soon as these hunter-gatherers migrated to America, for example, they hunted to extinction all the large Ice Age mammals.

Human “destructiveness” (if that is what predation is) has always been limited only by human knowledge and abilities.

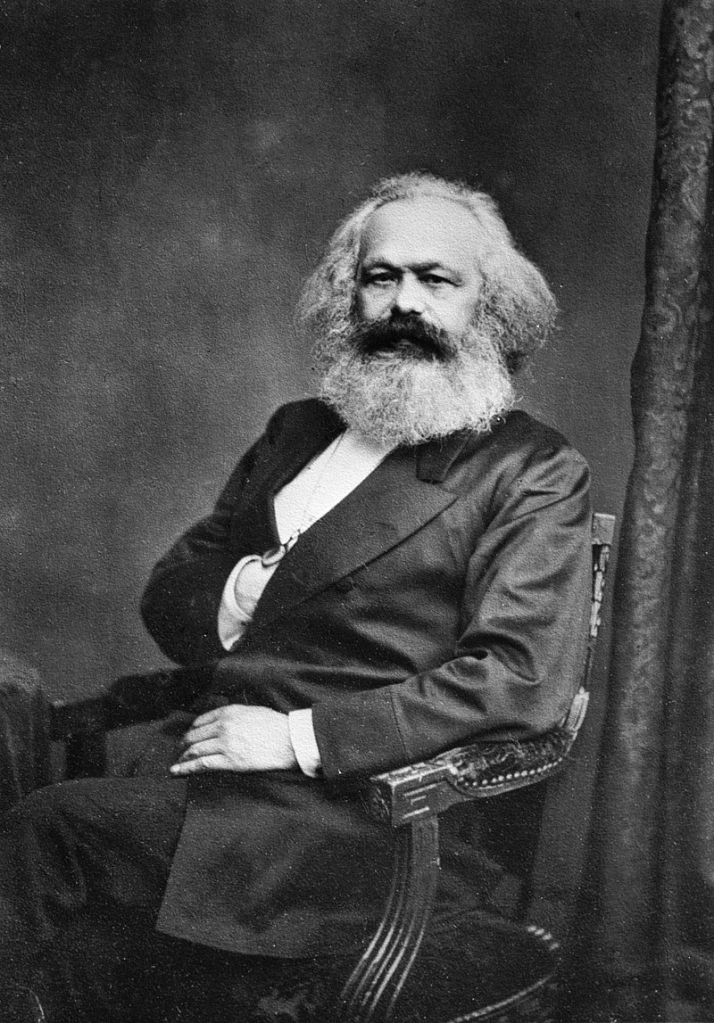

According to Karl Marx, human beings by nature transform the natural world into something recognizably human:

That is, into a human home.

According to Arne Naess, human beings should stop transforming nature and start conforming to it.

Are we by nature the masters and possessors of the Earth or are we by nature merely fellow citizens among other creatures?

These are ultimate religious and philosophical questions which are not likely to be resolved any time soon.

How should we interpret Naess’ distinction between deep and shallow ecology?

Although he rejected an “anthropocentric” perspective on nature (which he calls “shallow ecology“) his own celebration of the joys of communing with nature, of ecological diversity, the flourishing of all species and the harmony of local ecologies – all these reflect distinctively human values.

In other words, both deep and shallow ecology understand and appraise nature in relation to human flourishing.

Shallow ecology values nature only insofar as nature serves material or transient human desires.

Deep ecology values nature insofar as nature serves the spiritual and permanent human desires for the contemplation of the beautiful and sublime, for the wonder of the intellectual complexity of natural order and for humility in the presence of a mysterious gift not created by us.

I see all the moral implications of zoos, the good and the bad.

I will always feel saddened by the notion of caged animals, but if that is all they have ever known, if they would be unable to adapt to the wild because of a life of imprisonment, and if they are treated well, then in the name of preserving the species, I have no moral issue with visiting a zoo.

Seeing any animal anywhere, whether it is the hawks that circle the farmer’s field across from our apartment block in Landschlacht, or the cats that seek the shadows of Maltese gardens, or the strays of Eskişehir or Denizli, I feel honoured and privileged to bear witness to all God’s creatures great and small.

My failing is that, unlike the aforementioned Abela and his diving dog Titti, loyalty from an animal needs to be deserved.

Once helped, you become responsible for that animal.

Responsibility to an animal is akin to that of a child.

Once dependent upon you, they remain your responsibility.

I would love to be a pet provider, but a pet needs not only food and water and waste management, it also needs time and attention and care, again much like a child.

I know I would have been more sad and sympathetic to the tigers of l’Arka ta Noe had we visited them.

Ignorance is bliss.

Soon I will return to the Denizli Otogar.

Perhaps the kitten will be there again.

I hope with all my heart it will be.

I also hope with all my heart that it won’t.

Someone told me it’s all happening at the zoo

I do believe it

I do believe it’s true

It’s a light and tumble journey

From the East Side to the park

Just a fine and fancy ramble

To the zoo

But you can take the crosstown bus

If it’s raining or it’s cold

And the animals will love it if you do

If you do, now

Somethin’ tells me it’s all happening at the zoo

I do believe it

I do believe it’s true

The monkeys stand for honesty

Giraffes are insincere

And the elephants are kindly but they’re dumb

Orangutans are skeptical

Of changes in their cages

And the zookeeper is very fond of rum

Zebras are reactionaries

Antelopes are missionaries

Pigeons plot in secrecy

And hamsters turn on frequently

What a gas, you gotta come and see

At the zoo

At the zoo

At the zoo

At the zoo

At the zoo

At the zoo

At the zoo

At the zoo

Sources: Wikipedia / Google / Graeme Garrard and James Bernard Murphy, How to Think Politically / Paul Simon and Art Garfunkel, “At the Zoo“